‘Name?’

‘Amitabh.’

‘Can’t be only Amitabh. Amitabh what?’

‘Bachchan. Amitabh Bachchan.’

Alarm bells. ‘Are you related to Dr Bachchan?’

‘Yes,’ he hesitated, ‘he is my father.’

‘Then this contract cannot be signed today. He is my old friend. I cannot give you this contract without his permission.’

A fascinating excerpt from K A Abbas’s Sone Chandi Ke Buth.

Amitabh and my personal story began by coincidence. It is wrongly said that he came to me with a letter from Indira Gandhi. This may have happened with another producer. One day his younger brother came to me with Jalal Agha. At the time I was selecting artists for my film Saat Hindustani.

Jalal said, ‘Mamujan, this is Ajitabh. He does not want a role in films, but he has a photograph which you may like to see and thus get the seventh Hindustani you are looking for. We can then begin shooting the film.’

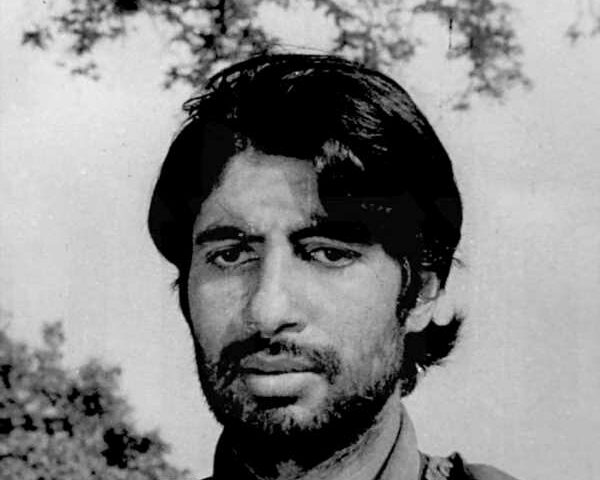

I said, ‘Let’s look at this one too.’ I used to see eight to ten photos every day. So I had very little hope of finding a suitable face. I glanced casually at the photo; it was demi-sized but there was something there which made me look again, carefully.

First, the boy was very tall; second, his eyes were beautiful; third, he was wearing the clothes I wanted this character to wear: churidar pyjamas, kurta and Jawahar jacket.

I had no idea who he was where he was from or whose son he was! Was he educated or was he a ‘matric fail’? ‘I will meet him day after tomorrow.’

Jalal’s friend said, ‘Fine, Sir, he will be here.’ I thought he was from Bombay.

‘I will wait for him until then… but no longer. Because this is why the film is stuck!’

‘The boy will be here,’ Jalal’s friend assured me.

On the appointed day, the young man stood before me. Tall, thin, fair and shy. I took one look at him… Anwar Ali, just as I had imagined him. I asked, ‘When can you start work?’

‘Work?’ he was startled. But his voice had a fine timbre, sounded good. ‘At once.’ ‘But,’ I said disclosing all the facts.

‘This film has seven heroes; the seventh is, in fact, a heroine. We can’t give more than Rs 5,000 to anyone — neither the seniors nor the juniors.’

‘I agree,’ the boy said. ‘But won’t you take any tests?’

‘No, we don’t take tests.’

‘I have the results of three or four tests. Should I show them to you?’

‘No. I don’t want to see others’ tests. By the way, who took these tests?’ He named four famous producers (if I reveal their names, it would be an insult).

I said, ‘In any case, I don’t take tests; I take the artist on face value.’

He smiled; an innocent look. The smile then extended to his eyes. ‘I didn’t understand… other producers took repeated tests, including dialogue delivery tests. They measured me, weighed me.’

‘And then?’ I asked.

‘Rejected. They said I was too tall, too ungainly, looked like a caricature and no heroine would want to work with me.’

‘This is irrelevant for me. I have six heroes, one heroine, and she is new. I have found the boy I was looking for.’

‘Found?’ he repeated my sentence.

‘Yes, found,’ I said.

‘Who is he?’ he asked.

‘You! Who else!’

Amitabh staggered, held the edge of the table. ‘What do I have to do?’

‘Sign a contract. I assume you can read?’ He told me he had graduated from Delhi University. He had performed in many college plays. To this, he added that he had been employed in a major Calcutta firm at Rs 1,400 per month. He had a free car, free flat. The emphasis was on ‘had’. ‘Until yesterday, not now.’

‘Why?’ I asked, a deliberately foolish question.

‘I resigned.’

‘Why?’

‘You called, so I came.’

‘I called only to see you. No one told me that you were in Calcutta. Had I known, I would have thought a dozen times.’ Then I made a mental calculation. ‘No train runs so fast. You flew down to Bombay?’

‘Yes,’ he agreed. ‘Ajitabh! Did he not mention this to you? He sent me a telegram, which stated: “Role fixed in Saat Hindustani. Have to report day after tomorrow.”‘

I exclaimed, ‘He told you such a big lie! What if I had refused to take you?’

‘I would have tried elsewhere! Sunil Dutt Sahib is planning a new film. Perhaps he would have taken me. In any case, I was fed up with the Kolkata job.’

In my heart, I appreciated the courage of this young man who had left a steady job on such a flimsy hope. Hope and selfconfidence, a good combination.

I said, ‘You can go to my secretary and sign the contract. But first answer a few questions. Name?’

‘Amitabh.’

‘Can’t be only Amitabh. Amitabh what?’

‘Bachchan. Amitabh Bachchan.’

Alarm bells. ‘Are you related to Dr Bachchan?’

‘Yes,’ he hesitated, ‘he is my father.’

‘Then this contract cannot be signed today. He is my old friend. I cannot give you this contract without his permission.’

‘So send him a telegram asking him. He will reply by tomorrow. But I have already written to him, telling him everything.’

‘I cannot write all this in a telegram. It has to be a detailed letter. I will write to him now and ask for a reply by telegram. You can go now. If we get his permission, you have nothing to worry about. You can come the next day and sign the contract.’

Amitabh left. On the third day, the telegram came. ‘If he is working with you, I am happy.’

Now I had no apprehensions, so I signed on Amitabh for Rs 5,000.

***

Amit’s image as the ‘angry young man’ also started with Saat Hindustani. The character, as I had written it, evoked mixed emotions in the other characters — suspicion, discrimination, dislike — all because he was Muslim. The prejudice would become palpable from time to time — while eating, drinking, etc. But in the end, the one who is the most fragile, timid and weakest proves the bravest.

The Portuguese police inflict the worst kind of torture on him. In the torture chamber, they hook him with electric wires. The current hits his vitals and he faints. They throw water on his face and begin to interrogate him, ‘Who are your accomplices in Goa?’

The boy refuses to reveal any names and when the cop continues the interrogation, he spits on his face. More lashes break the flesh, but he still doesn’t say a word. A blade then slices the skin off his feet which are tied with a rope. At the end they throw him across the border. ‘Now, crawl back to your motherland.’

In his best close-up of Saat Hindustani, Amitabh speaks the words, ‘We Indians don’t crawl.’ He stands upright on his bleeding feet. With trembling legs but straight and raised head he walks towards India.

Excerpted from Sone Chandi Ke Buth by K A Abbas, edited by Syeda Hameed and Sukhpreet Kahlon, with the kind permission of the publishers, Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House India.

Source: Read Full Article