After a lifetime of showing us what it means to ‘act at the top of one’s bent and never hit a false note’, Mammootty had the good sense, in the third act of his career, to pare down his style, become less mannered, draw directly from life.

And getting a performer like that to play characters who seem ‘completely dead inside’, is, in my view, a betrayal of his legacy, his still-burning ambition, and his still-sharp feelers, observes Sreehari Nair.

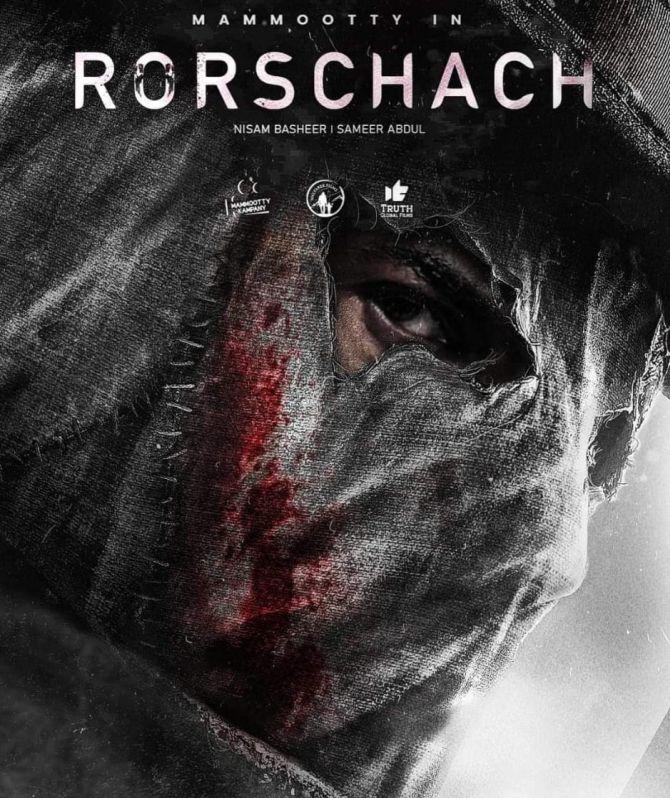

Nisam Basheer’s Mammootty-starrer, Rorschach, is many movies in one, each running at a different speed. But that’s not all.

Basheer is first and foremost resolved on denying you every ‘easy pleasure’ there is in the superstar movie manual. (I suspect that the young director and his writer, Sameer Abdul, know all too well that most Indian cinephiles make a big deal of such small consolations).

So Mammootty does not get a grandiose entry scene in this movie.

Not just that, Rorschach, defiant about not bringing in its big star at a major plot-turn, hurls him head-first into the narrative.

He is Luke Antony, an NRI on a vacation, and the movie opens with him walking into the local police station of a comatose village in the middle of a cricket-filled night to file a missing report. ‘I took a wrong turn, hit a tree, and passed out. When I woke up, my wife…’

These are about the only words that our sullen hero speaks in the first twenty-five minutes of Rorschach.

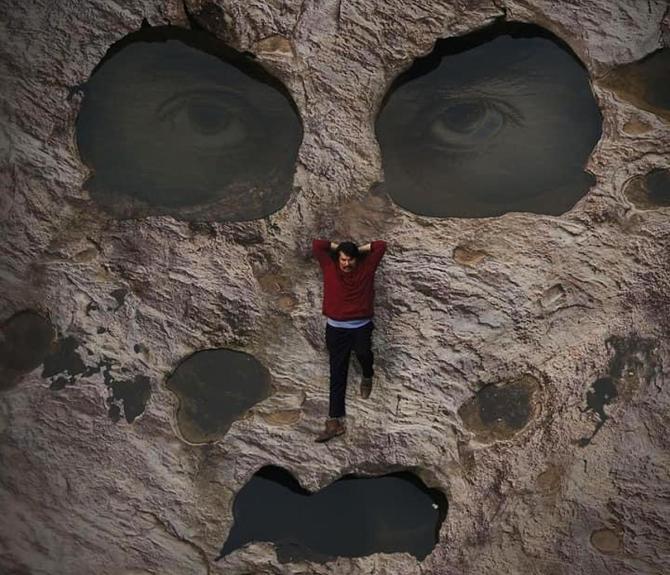

For after the missing wife is not found for months, Luke settles down on a rock-face in the village, greeting with grim nods and an occasional smile all those who approach him.

In the scenes set on the rock-face he’s one hell of a hermit, is Luke, and the sluggish stream below seems to be recounting the story of his isolation.

A man so taciturn is played by an actor whose voice had made a whole generation of moviegoers jolt up in their seats… what is this but yet another example of ‘easy pleasure defiantly denied’?

But then the movie turns. By a quirk of fate, Luke finds himself in a godforsaken house in the village, and a piece of theatre begins to unexpectedly unfold.

The hermit starts a series of conversations with a ghost, and Hamlet immediately springs to mind.

What’s more, a skull is thrown into the mix — but it’s not a noble skull like Yorick’s, and in more than one scene Luke Antony uses it as an ashtray.

The skull-as-an-ashtray image should, however, be seen in the right context; for this is Hamlet on a strict diet of German Expressionism: full of allegories, Dutch tilts, sudden voiceovers, and disjointed spaces.

Speaking of disjointed spaces, the house that Luke moves into is only half-constructed, but even this show of shagginess must be viewed as representing ‘something’ (Unfinished business, a dream not completely realised… oh, don’t you hear swooning and moaning sounds emerging from the cinephile gallery already?)

The house, we are told, had belonged to Dileep (Asif Ali, forever hiding behind a Klu Klux Klan hood), who has grave connections with Luke’s wife. And when Luke starts to meet up with Dileep’s family members, we can see how the characters’ everyday looks have been painted over and distorted, as if to highlight the very condition of their souls.

So Luke, whose plans were severely muddied after the loss of his wife, now starts appearing in public wearing soiled blazers. And the man evidently cannot sit still: When paired with a stiff upper-body, his leg shaking becomes a metaphor for how ‘tied down’ he feels.

A question for all those who are still beholden to the Germans: How can the works of Ernst and Otto and Max compare to an expressionist fervor like this?

Also on the soul-evaluation trail, we come upon Bindu Panicker’s Seetha, Klan-man Dileep’s mother. Seetha’s beat-up face, in which choked blood salts and wastes are clearly outlined, testifies to how well she has been slow-poisoning her family.

Panicker gives a striking performance, but when you think about it later, her fits of confession and her gory acts would seem to you to lack an objective correlative. It’s a striking performance precisely because it evokes contrasts that are too stark; much like those evoked by puppy-loving gangsters and murderous clowns.

That said, this movie is nothing if not ‘stark contrasts’; so much so that when a character stares wistfully into void, the makers feel obliged to qualify the gaze by running over it an English number.

The song is meant to imply the wail of a helpless spirit, or something in that range, though to my ear it sounded like one of them drawled-out jingles that SUV companies use to advertise their philosophy of Live it Up!

But you should be grateful to Rorschach‘s moments of perfumed wistfulness; for otherwise, when the characters in this movie suffer, they ‘really’ suffer: Furrowed brows; bulging eyeballs; and Kottayam Naseer as Shashankan, Dileep’s brother-in-law, his beard a facsimile of his conscience, trembling as if it were a beehive buzzing with guilt.

I may be exhausting my poor man’s puns on things that Nisam Basheer and his team see as ‘symbols swollen with meaning’ — and the movie is mostly symbolisms or joyless post-modern touches.

For evidence of the latter, consider Mohan Raj, famous for playing the brawling, strapping Keerikkadan Jose in Sibi Malayil’s Kireedam.

In Rorschach, Mohan Raj is installed as a man who spends his autumn days watching WWE matches on television and who, as a wrestling bout builds and builds in intensity, pees as he applauds.

The brawler as an incontinent quack — how’s that for a post-modern touch crackling with flashes of pain?

I know all this sounds a bit too Stoic; which is why I go back to my earlier assertion that Rorschach is many movies in one; and starring in a separate movie almost, as if running against the freight train of history, is Sharafudheen.

Sharafudheen’s performance as Sateeshan (who happens to be a distant relative of Dileep) is one of such vitality and truth that it begins to offer a solid footing for the other characters to find some rhythm.

While Luke shadows Dileep’s family, Sateeshan shadows Luke, and it’s in these moments that Rorschach breaks out of its slugged consciousness.

The performance is, in many ways, characteristic of Sharafudheen’s craft and his career thus far: with him you never know what to expect; and often, he pops out of a corner and expands his dominion.

When Sateeshan takes one look at Luke and classes him as a ‘killer’, you can feel the character’s perception trumping the scriptwriter’s line.

Laying at his whoremaster’s feet a marriage proposal, Sateeshan’s mother offers him her ultimate attempt at progressive thinking.

‘I don’t mind if she’s a widow,’ says the mother, to which our man turns around like a loaded weathercock and replies, ‘I do mind it!’

Rorschach‘s natural texture and its scenes involving Sateeshan are as different from each other as the deserts of Nevada and the electric signs of Las Vegas; and Sateeshan’s shrewdness is without doubt the shrewdness of the cardsharp, the quick-study, the failed engineer who pores over the laws of mechanics just so that he can set tripwires.

There’s something carnal about the man’s cynicism.

He keeps tabs on the woman whom he’s ‘merely’ balling, and their numerous back-and-forth tell you about those times when each must have slipped into the other’s privates a bit more than just fluids; you get the sensation that this odd couple has been passing on to each other a part of their individual substance and qualities.

Sateeshan, the salacious fox, is far and away the best thing about Rorschach. And his bright untrusting eyes, in which self-preservation and rapine reside by turns, provide you with hints as to what’s wrong with the rest of the movie: elsewhere, the tricks don’t come out of real feelings.

The camera may not tilt for Sharafudheen, for him the voiceover may not boom, and yet, while Rorschach is concerned primarily with the extremities of human nature, the actor makes you care about that which lies between two dramatic highs.

He makes vivid for you the hedges, the hearths and the whorehouses that make up the story, and by the way he moves inside a frame, by the way he drops or picks up the ends of his mundu, he forces you to take into account the specific history and culture of this otherwise generic piece of land.

Though the energy of Sharafudheen’s Sateeshan is at odds with what the makers of Rorschach were going for (and maybe for that very reason) it’s a performance of the highest quality — a fluid impressionistic portrait in a world of tight-fisted expressionism.

Also, it’s when you juxtapose Sateeshan with the other personages in this movie that you begin to see the lie in that hoary term — ‘grey character’.

You see the lie because someone like Sateeshan stimulates you to think and write about him in all sorts of fresh ways than leads you into that terrain of casual terminologies where the only thing you can do is throw up your hands and declare, ‘Oh, he is grey.’

And how sad that a tryst with this shade of unhealthy grey has come searching for Mammootty just as his lightness as an actor and his comic brilliance were taking full effect.

Just as he was becoming great at such dense stuff as ‘dispensing teashop wisdom while simultaneously chewing down a mouthful of puttu‘, they are getting him to play drillmaster-type one-note characters who have a problem with expressing themselves fully, and who keep their audiences at an arm’s length.

As in Puzhu (a movie so asinine that it would make the manifestos of our political parties seem like repositories of thoughtful pearls), all I could see in Rorschach was a serviceable actor, taking a whack at the template of the ‘cold character’, while all the time wearing a Mammootty mask.

The mask may just be the perfect actor’s accessory to bring to a movie like Rorschach , in which a combination of suspense and confusion and ambiguity is used to produce in the viewer a kind of numbing fascination. But to think that they are inflicting this on Mammootty!

After a lifetime of showing us what it means to ‘act at the top of one’s bent and never hit a false note’, Mammootty had the good sense, in the third act of his career, to pare down his style, become less mannered, draw directly from life.

And getting a performer like that to play characters who seem ‘completely dead inside’, is, in my view, a betrayal of his legacy, his still-burning ambition, and his still-sharp feelers.

Though the ‘unfeeling’ Indian hero, with no nerves connecting his punishing hands to the pain centres in his brain, seems to be the new mainstream cinema normal, a movie like Rorschach gives this concept a further boost.

Rorschach‘s hero is so unfeeling and so dead inside that he prefers to be cloistered in dimly-lit houses, tumbledown cars, and clothes that continue to display the spatters of last month’s sludge.

I suppose the idea, here, is to project the hero as an ambassador of constipated austerity — the perfect medicine for these times when our interest in cine-stars is being offset by our knowledge that armed with a high resolution mobile camera we too can glisten like the Gods!

But still, poor Luke Antony! For all his suffering, he is also weighed down by self-absorption.

There’s not one scene in the movie where he looks at his wife with anything close to yearning or desire; and so, we cannot empathise with his loss except, perhaps, in plot-terms.

As a matter of fact, the sole dharma of Luke Antony’s wife seems to be to get away from Luke so that she can later sidle up to him as his symbolic conscience.

A question then: Is the unfeeling Indian hero’s cold heart just a subtle way of suggesting his rapidly enlarging prostate?

Every glowing review of Rorschach has reserved special praise for the film’s leading man (Though most of these reviews don’t go beyond that trite line of ‘Mammootty not looking 71 at all’).

On the other hand, even the reviews that have commended Sharafudheen, talk about him as if he were just one of the many good things in the movie.

This is baffling, and it points to a deeper malaise. Because, as I see it, whom the cultural critics of a country pick when asked to choose between ‘a hero who has numbed himself out’ and ‘an actor who gives a movie genuine life-force’ may just be the Rorschach test to judge that country’s emotional health.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article