Abhishek Bachchan's The Big Bull and its big bucks ambition raise a pertinent question: how does Hindi cinema show wealth and why the rich are always the villain?

Abhishek Bachchan is turning out to be the leading interpreter of ‘money’ on Hindi screen. Dressed in a shiny suit (though not shiny enough compared to dad Amitabh Bachchan’s ‘Saara zamana’ whose lightbulb sleeves could have electrified a small village) he rapped to ‘Sabse bada rupaiyya’ in Bluffmaster! (2005), a tune originally associated with comedy king Mehmood from the mid-1970s. He broke rules flamboyantly in pursuit of wealth in Mani Ratnam’s Guru (2007) in what is generally regarded as one of his better performances that even Ambanis can approve of. Now, in his new film The Big Bull, which dropped on Disney+Hotstar on April 8 and whose reviews are mixed at best, he proclaims, “I’ll be India’s first billionaire.” In it, Bachchan plays the Dalal Street trickster Hemant Shah. Sounds familiar? Perhaps. Hansal Mehta’s recent web series Scam 1992 had a strikingly similar plot. Both are inspired by Harshad Mehta’s steep rise and fall. To viewers who were young enough to remember the 1990s there’s no need to explain who Mehta was. To the rest, it would suffice to say he was a charismatic stockbroker who made a killing at Dalal Street with his exploits but was soon done in by his venal ambition. A Gordon Gekko kind of a guy for whom greed was good. Or shall we say, greed was God?

“Note ka maalik banne ke liye ussey kamana padhta hai,” prescribed Saif Ali Khan’s bad boy Shakun Kothari in Baazaar (2018). For Emraan Hashmi’s small-time hustlers, the good and bad are two sides of the same coin (Crook, 2010) which gives his many screen characters a free pass to subvert the rigid rules of morality in his favour. Even Bachchan’s own Gurukanth Desai from Guru defends his unscrupulous practices by invoking Gandhi in the film’s climax. It may have been filmmaker Mani Ratnam’s attempt to reach for a Gordon Gekko/Tony Montana/Godfather sort of redemptive moment in the eyes of the public. “I am the public,” Gurukanth Desai snaps in a whistle-worthy scene. From Kishore Kumar mocking money as a magic wand in Paisa Hi Paisa (1956) to Akshay Kumar chipping in with ‘Main baarish kar doon paise ki jo tu ho jaaye meri’ in De Dana Dan (2009) a decade ago, Hindi cinema has come a long way in terms of its relationship with money. Even Shah Rukh Khan of Raees who says, “Ammi jaan kehti thi, koi dhandha chhota nahin hota aur dhandhe se bada koi dharm nahin hota,” is a far cry from the dreamy eyed Rahul from Yes Boss (1997) who firmly believes that, “Dil ki gali bohot chhoti hoti hai. Usmein ya toh paisa reh sakta hai, ya pyaar.”

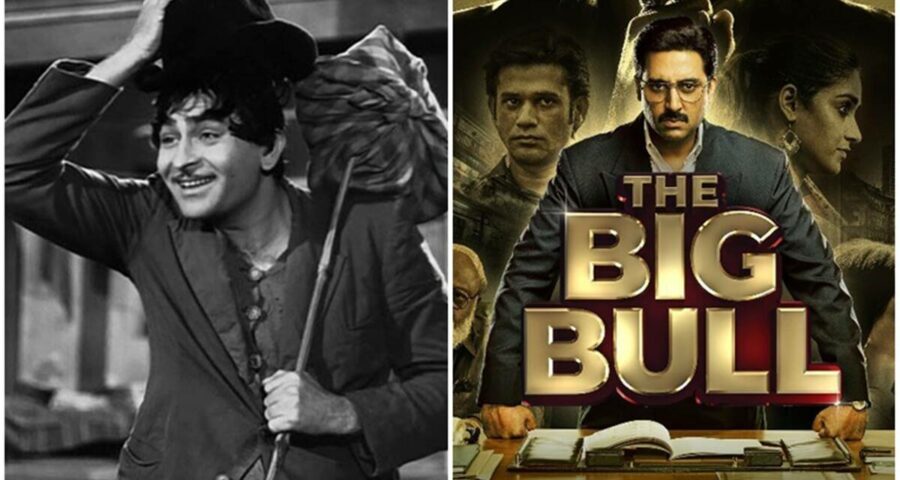

Paisa and pyaar are two of Bollywood’s oldest tropes, dating as far back as the marvellously timeless Shree 420 and Pyaasa. Raj Kapoor’s Shree 420 best captures the essence of these twin attractions. It sometimes feels like for this most enduring of Hindi classics it was not just enough to be pro-poor. It had to be anti-capitalist. Its eponymous hero Raj (Raj Kapoor) is forced to let go of his idealism and honesty, which had endeared him to his lady love Vidya (Nargis) in the first place, for a life of crime. Or towards Maya (Nadira), as the vamp is called. Kapoor’s tramp gets his first lesson of the heartless nature of a big city the moment he lands in Bombay. He’s told by a roadside beggar, “People can only hear the jingling of money here.” The city’s evil influence corrupts the naive Raj. “Iss duniya mein toh saans lene ke liye bhi paisa chahiye,” he tells Vidya, justifying his stand. Raj eventually mends his ways, only because the uncompromising Vidya is the film’s moral force and wouldn’t indulge his wrongdoing.

In the socialist India of 1950s, for Raj to be a hero he needed to be redeemed in this way. In Bollywood, the rich have always been the villain. In other words, the cunning moneylenders and landlords now replaced by billionaires with net worth and corporate empires. Take any number of films from that era and you find ‘money’ to be a problematic affair. In Pyaasa, Guru Dutt is a struggling poet in whom the audiences immediately place their sympathies while the elite Rehman is the toff who makes the moneyed class look bad. So is the foreign-returned Kundan (Jeevan) in Naya Daur. Then, there’s Dharmendra who plays the humble teacher and novelist Ashok in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Anupama (1966). Sharmila Tagore’s Anupama belongs to a rich family who has a troubled relationship with her father. Ashok is certainly a man without means but as he reminds her father, “love and sacrifice” compensates for all his deprivations and desperations. From Neecha Nagar (1946) and Waqt (1965) to Dulhe Raja (1998) and Dhadkan (2000), this classic rich girl-poor boy confection has had a lasting impact on Hindi audiences. One of the chief objections in Mughal-E-Azam, Hindi cinema’s ultimate magnum opus, is that the heroine (Madhubala) is a commoner and hence, no match for the Prince Charming (Dilip Kumar) who will soon be India’s emperor. A hands down win for money, privilege and power.

Looking at the 1970s cinema tells you that capitalism was still very much a foe that needed to be defeated. The hero, though, got a step up — no more poor he now belonged to the working class. Amitabh Bachchan’s Vijay from Deewaar (1975) piles up an empire but is not rich enough to buy his mother’s love. Again, the tantalising battle between ‘money’ and ‘love.’ Bollywood’s rule seems to be simple. Profit, if lavished on the needy in a Robin Hood-esque generosity of spirit, does not remain the evil that it inherently is. Cue the countless gangster hits, from Agneepath (1990) to Raees (2017). Or the ‘heists’ which mine money for popcorned laughs. Remember “Mayyat ka chanda” in Andaz Apna Apna (1994)? “Paisa kya cheez hai?” asks Raju (Akshay Kumar) in Hera Pheri (2000) before replying, “Haath ka mail.” Even before having possession of the filthy lucre, the glib Baburao Ganpatrao Apte (Paresh Rawal) knows how to spend it all. He has a ready laundry list of his own which includes booze on tap.

Many critics have pointed out that the economic liberalisation of 1991 unlocked India’s boundless ambition. The sky was the limit and it gave rise to the flourishing culture where money and consumerism could buy you happiness. Even sweet revenge — ask Suniel Shetty whose rags-to-riches (“50 paise to Rs 500 crore”) theme fuelled 2000’s Dhadkan. The 21st century’s economic boom changed the we lived our lives and it steered Bollywood along the dirty path of profiteering, bewilderingly couched as a dream towards a better life. Emraan Hashmi whose career has been a mass-friendly medley of free enterprise, lip-locks and criminality, says in Jannat, “Jeb khali ho tabhi toh sapne dekhne chahiye.” He makes a fortune as a cricket bookie but meets his just comeuppance in the end. Some things, it seems, have not changed. Heroes wanting to make a fast buck are still getting punished. Capitalism may be a dominant force in today’s resurgent India but it still cannot trump socialism as an apostle of moral certainty on Hindi screens for another few decades. Till then, the billionaire’s club will continue to be the devil. The world of the Tatas, Ambanis, Adanis and Birlas have their task cut out, it seems.

Source: Read Full Article