With A Teacher, Hannah Fidell (creator and director) is dissecting themes she had first explored in her 2013 film of the same name: grooming, unequal power dynamics, and abuse

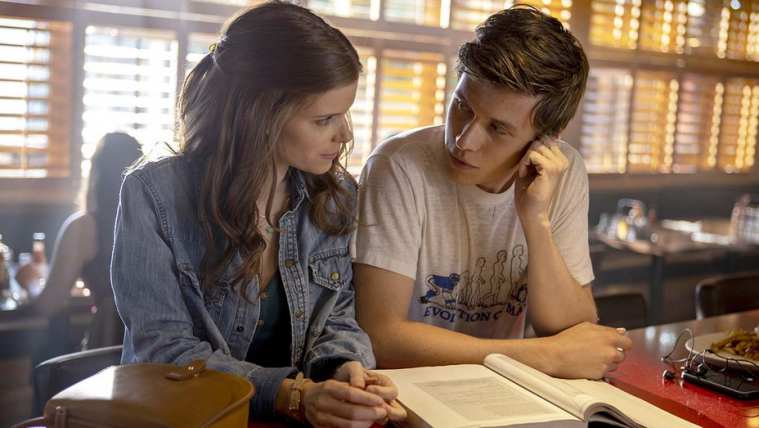

A Teacher — the ten-part revelatory miniseries on abuse — resembles a doomed love story. Claire Wilson (Kate Mara) and Eric (Nick Robinson) are star-crossed lovers. She is the new English teacher at a fictional high school in Texas and he is the misfit student. She is stuck in a listless marriage, he is caught in an indolent high school limbo. Having grown up with an alcoholic father, she was compelled to adult prematurely. Staying with a single mother and two brothers, he is forced to be the adult of the house. She agrees to tutor him on the sides. He is inexorably attracted to her. After snubbing his advances, all bindings collapse. But what begins as a reckless liaison takes the shape of a guarded alliance. They go for a romantic escapade to celebrate his 18th birthday. Claire and Eric fall in love. Their secret, however, is out soon, alarming the school authorities and upending their lives.

Hannah Fidell (creator and director) is not depicting a tale of missed chances. She is, as evidenced in the shattering finale, dissecting themes she had first explored in her 2013 film of the same name: grooming, unequal power dynamics, and abuse.

When the MeToo movement broke out in 2017, it revealed multiple instances of systematic abuse. These occurrences follow a recognisable pattern: the autonomy of control enjoyed by one and the complete lack of agency suffered by the other. With A Teacher, Fidell spotlights other anomalous narratives of abuse, those that don’t fit into the decipherable pattern but, as she compellingly puts forth, have a pattern of their own.

In 2016, I messaged a man I had admired for years. I liked his work and after overcoming trepidation I wrote exactly that. He replied instantly, thanking me. I was one of his young readers. My message reassured him, he wrote back. And his, gratified me. What started out as cursory acknowledgement soon devolved into regular depraved conversations. At 24, fresh out of home and emboldened to feel like an adult not just in age, I feigned comfort till I could not tell the difference. Every question of his was met with robust assurance, every concern was dissolved with impassioned consent. I was too scared to feel naive and too young to know I was being precisely that. When he asked if I was sure, I convinced him there was no doubt. When he told me not to message at a certain time I complied obediently. I learnt to hide his name with practiced stealth, maintain secrecy with devout sincerity. He was in love, he said, so was I, I was certain.

The relationship did not end well. It was not supposed to. But rather than acknowledging it as abuse I held on to it like an unpleasant relationship, implicitly taking blame in the unfolding. For, I kept asking myself, did I not say yes, each time with more conviction? It took me years, a social media upheaval, and my closest friend opening up about a similar experience to identify it as an inherent pattern.

Youth complicates agency. It lends an illusion of control when one, in fact, is being controlled. At 24, age was an approximation of my inexperience, an identifier of still being immune to power balance. My certainty was my defiance to be right even when unsure; consent was a reaction rather than a realisation. Drawn by admiration I let him navigate the moral compass while shouldering complete responsibility for the pitfalls. Eager to maintain ties, I accepted any nature it offered. The dynamic made me feel empowered which I mistook for power.

Eric, at 17 does the same. The reversal of gender does not limit the yielding of power nor does the fact that he pursues her and consents when asked. For, Fidell argues, what constitutes abuse is not the arrangement of a narrative but that it can be irrefutably controlled by one. What constitutes abuse of power is not just the suppression of voice but also the impression it creates of having a say.

Claire, 32, older and knowing better, had the reins all along. She took him out, met him in private and showed some lines can be crossed till all were blurred. She pleased him, he appeased her. Love is a story she told to absolve herself. It is a story he believed to sanction his powerlessness.

A Teacher ends with a dramatic ten-year leap. Both meet again. She apologises, reasons the incident spoiled her reputation. He says it altered his life. Eric, 27, evaluates his past with the benefit of hindsight. Claire, 42 and a mother, does so with foresight. From their conversation emerge the invisible lines of control she wrested all along. It serves as a narrative closure, transmuting the tragic love story into a tragedy. For many the urgent moment is wishful thinking, an exchange they play out in their heads to feel better. But by literalising it, Fidell clears the ethical ambiguity they have long wrestled with. For, love without responsibility is abuse without a name.

(A Teacher is streaming on Disney+ Hotstar)

Source: Read Full Article