Domicile-based preferential policies indict the economy as a whole, suggesting a pessimism about both education and job creation

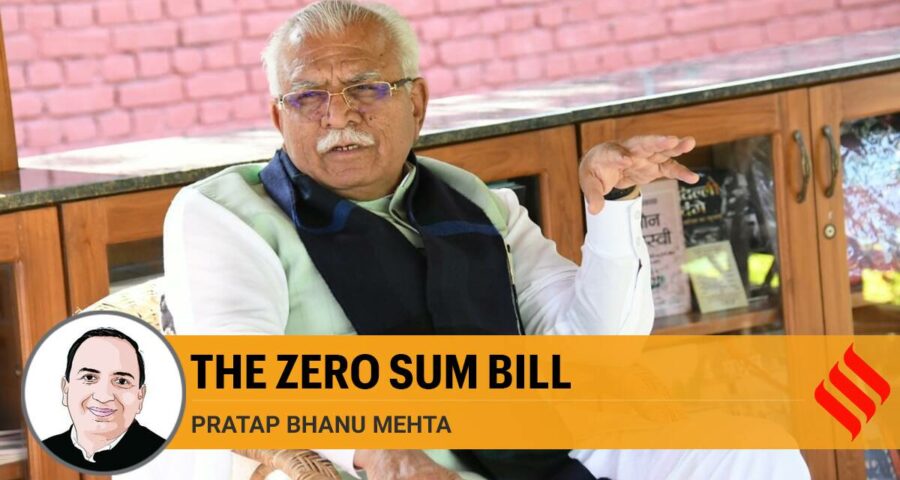

The Haryana government’s State Employment of Local Candidates Bill 2020 is constitutionally dubious, economically myopic, socially divisive and politically cynical. The Bill reserves 75 per cent of new jobs in private establishments under a compensation threshold of Rs 50,000 for Haryana residents. This is part of a growing pattern of domicile-based preferential policies, where state after state is flirting with laws of this kind. Andhra Pradesh has mandated 75 per cent reservation for locals; Karnataka is toying with the idea of reserving all blue collar jobs for locals; Madhya Pradesh has announced that public employment in the state be reserved for state residents. The last time there was such a contagion of domicile-based preferences was in the 1970s, when states such as Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh issued circulars directing employers to hire local residents.

The Haryana Bill is constitutionally indefensible. The Constitution prohibits discrimination based on place of birth. The right to move freely in the country and reside and settle in any part of it, the right to carry out any trade or profession, are all established rights. Article 16(3) does, in principle, enable Parliament to provide for domicile-based preferential treatment in public employment. But the right to enact this exception has been given to Parliament, not to the states.

In fact, Article 16(3) seems to have been a clever piece of constitutional engineering by Ambedkar. There were voices in the Constituent Assembly, most notably Mahavir Tyagi, who were advocating for residential qualifications as the bedrock of a strong federalism. He argued that if there were no residential qualifications, provinces would not be able to enjoy “self-government” and it would “go against the real spirit of Swaraj.” There were also a plethora of existing rules. In the debate on November 30, 1948, Ambedkar conceded that “you cannot allow people who are flying from one province to another, as mere birds of passage without any roots, without any connection with that particular province, just to come, apply for the post and take the plums away.” But by decreeing that only Parliament had the right to make exceptions, Ambedkar ensured that such rules would not be enacted, simply because Parliament would favour uniform rules across India.

The constitutionality of domicile-based employment preferences (unlike preferences in education) has never been frontally tested. The courts have not shown an urgency in pricking this balloon. But almost all the existing case law that impinges on the matter clearly indicates such laws are unconstitutional. In Pradeep Jain vs Union of India, the court had indicated this direction; in Kailash Chandra Sharma vs State of Rajasthan, the court had warned against parochialism. The Andhra Pradesh Bill is sub judice in the high court.

The Supreme Court will hopefully rule on the constitutionality of the Bill. But the Bill has ramifications beyond constitutionality. It is an exercise in political cynicism: The government knows it will be struck down. But it is all the more dangerous for that reason. First, because this kind of constitutional cynicism is now not an exception but has become a contagion. Second, even if the Bill is struck down, such a high wire act is meant to fuel the flames of localism. As the Shiv Sena had demonstrated in the ’70s, political parties can bring formal and informal pressure to bear on industries and enterprises, once you make preferential treatment of residents a wedge issue. Third, the Bill now exposes the bad faith of political parties on private sector reservation more generally.

We can debate where private sector reservation is desirable or not. But the one prong of a defence used to be that the private sector cannot be subject to the same yardstick as the public sector; imposing reservation would not just interfere with freedom of trade and business, it might also be a form of expropriation. Given the variety of parties now espousing domicile-based reservation, the argument that the “private sector” can be protected will be an argument in bad faith; and arguably the case for reservation for social justice is stronger than the case based on domicile. Fourth, these bills will open up a new form of competitive ethnic politics. It is odd that a state like Haryana which has benefitted from being part of a cosmopolitan zone like NCR should unilaterally impose reservations. Would NOIDA or Delhi be in its rights to bar Gurgaon residents from working there? Fifth, there is patent class discrimination: If you are rich, privileged or highly skilled, there are no entry barriers in accessing any labour market. But we shall put entry barriers on lower skilled migrants; our own internal version of an

H-1B visa.

The economic consequences for Haryana are uncertain, in part because the government itself is cynical about the Bill. The Bill has several provisions that can provide for a workaround: You can apply for an exemption if there is not enough local talent; the fines for non-compliance may allow companies to absorb the cost of violation. But the greatest damage the Bill does is to increase the discretionary power of the state, almost taking us back to a license permit raj, where companies will have to bargain, or worse, bribe the state for exemptions. This is the antithesis of regulatory reform.

These bills are a canary in the mine. States are still not entirely comfortable with migration. They militate against the ideal that any Indian should be able to countenance the prospect of making a life in any part of India. Second, they reveal the fact that slogans of “One India” are weaponised, to be used when convenient. In some ways, 75 per cent reservation in private sector employment is a worse form of exceptionalism than other forms of asymmetric federalism like Article 370 that the BJP railed against. The sociology of the Bill is also interesting: It seems to want to protect, not the most vulnerable workers, but the educated who cannot seem to be able to compete in a tight labour market.

But the fact that states feel the need to enact these bills is an indictment of the economy as a whole: They suggest a pessimism about both education and job creation. So we have returned to a world of zero sum thinking. It looks like Mr Khattar does not have faith in Mr Modi.

This article first appeared in the print edition on March 5, 2021 under the title ‘The Zero Sum Bill’. The writer is contributing editor, The Indian Express.

Source: Read Full Article