The Spanish flu or the H1N1 influenza of 1918 infected 500 million people worldwide, an epidemic far more cataclysmic than Covid-19. The artists and writers who suffered from the virus, delineated their personal experiences in their works.

Written by Shreya Banerjee

“I had a little bird.

Its name was Enza.

I opened up the window,

And in flew Enza.”

(Old nursery rhyme)

The Spanish flu or the H1N1 influenza of 1918 infected 500 million people worldwide. The number of deaths were estimated to be 50 million. In India, the flu was referred to as the Bombay Influenza which claimed around 17-18 million lives.

In terms of impact, scale and mortality, it was an epidemic that was much more cataclysmic than Covid-19. In spite of having such a grim legacy, there is barely any mention of it in our literary or cultural texts. War poems from the same time frame (1914-1918) have been valourised and taught in school/college curriculums. In contrast, the artists and writers who suffered from the virus and delineated their personal experiences in their works remain unacknowledged in the convolutions of history.

The Modernism movement of the 1900s came with war and disease. The development of modern industrial societies and the rapid growth of cities inundated with reactions to the horror of World War 1 led to a deconstruction and reconstruction of previously held philosophical, aesthetic, political, and social beliefs. The wholeness of man was facing a spiritual crisis. Malcolm Badbury begins his work Modernism by stating that “Overwhelming dislocations, those cataclysmic upheavals of culture, those fundamental convolutions of the creative human spirit that seem to topple even the most solid and substantial of our beliefs and assumptions, leave great areas of the past in ruins, question an entire civilization or culture, and stimulate frenzied rebuilding.”

What lies at the heart of the art and literature of this time is the disjointedness that characterised this period, along with the search for a higher structure that could perhaps anchor these severed pieces. What Peter Gay calls an ‘earthquake’ whose ‘aftershocks’ were felt in France, Germany, Italy’ in art movements such as Cubism, Dadaism, Surrealism and Futurism.

ALSO READ |Lakshadweep: An isolated island that became a melting pot of cultures

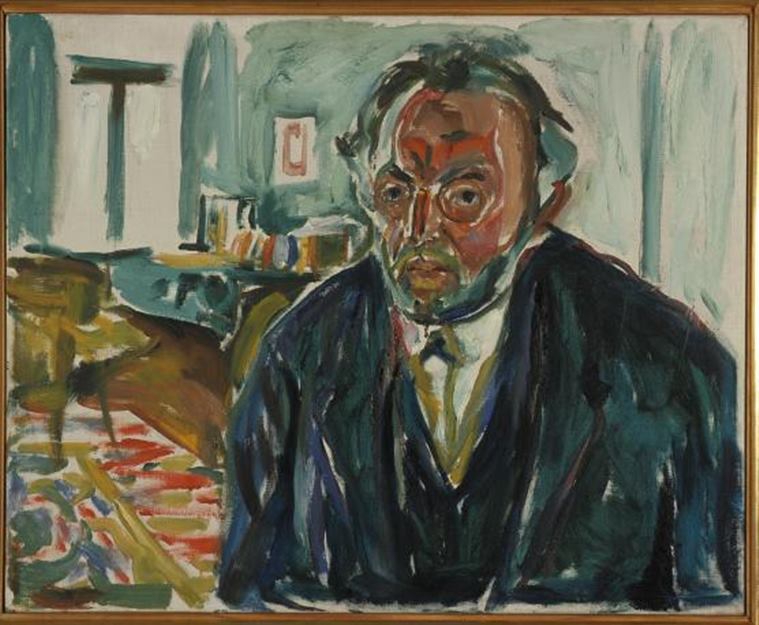

Norwegian painter Edward Munch

In 1919, Norwegian-born expressionist painter Edvard Munch fell victim to the H1N1 influenza. Munch is celebrated for his artistic ability to translate expressive inwardness, internal conflicts, and emotions through his works. Munch’s painting titled Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu was painted in the midst of his illness while he was in quarantine. The work is an artistic testimony that reflects the frailty of life in a world ridden by disease and death. What draws our attention is the piercing gaze of the artist’s likeness. A gaze that seems heavy with delirium, weakness and pain. The gaunt face, parted lips, thinning hair, pale yellow skin is unsettling.

Munch’s second painting Self Portrait After the Spanish Flu portrays the artist in the early stages of recovery. In this depiction, Munch seems to have regained a bit of his vigour. The blood seems to have returned to the eyes and face. His beard is longer and he is seen wearing a green suit. Green may be symbolic of the return of health and tranquility. Although the portrait of the artist holds within it’s frame a continuing sense of discord and exhaustion, the reappearance of colour to his face is an encouraging detail.

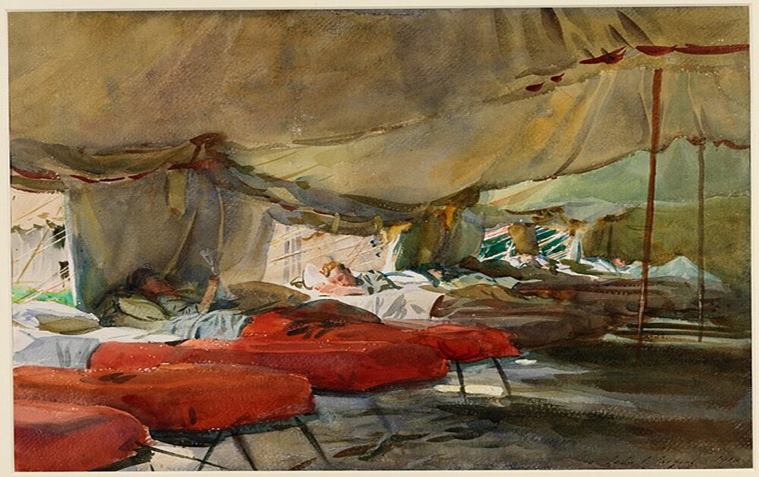

American artist John Singer Sargent

In 1918, John Singer Sargent created a watercolour titled Interior of a Hospital tent while he was inflicted with several bouts of the influenza. The artist spent weeks in a hospital tent where soldiers recovering from war wounds and episodes of the deadly virus were treated next to him. The British War Memorials Committee commissioned Sergeant to work as a war artist. He was assigned to sketch British and American troops in combat. While working in Northern France, he contracted the Flu. The painting depicts the internal workings of the hospital tent. A succession of military cots marked with blankets either red or brown to denote the presence (red) or absence (brown) of contagion. In the fourth red cot is perhaps the Sergeant himself. The remaining cots are occupied by soldiers wounded from battle who ran a huge risk of contracting the virus from the inflicted few. Above the beds is a brown canopy looming over the activities of the tent. Sargent describes his days at the hospital tent as ‘horrific’ and ‘fitful’, punctuated with “groans” of the wounded and “coughing” of the infected. Singer’s watercolor is exhibited in the Imperial War Museum in London. This sui generis work of art offers a frontline glimpse of the two concurrent conflicts occurring at the same time.

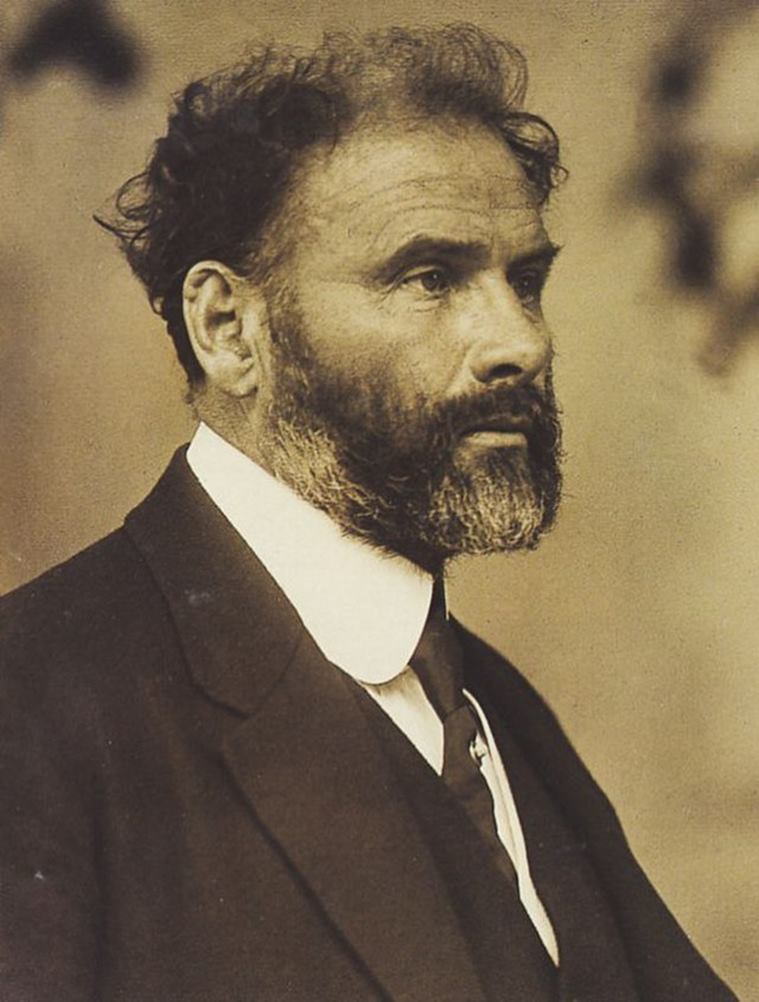

Austrian painter Gustav Klimt

Austrian symbolist Gustav Klimt suffered a severe stroke in 1918 that left him paralysed. In the course of hospitalisation, the artist contracted the Flu. He fought with the virus for more than two weeks but ultimately succumbed to pneumonia induced by the viral strain.

Gustav was also the mentor and muse of young Egon Schiele. Schiele visited Klimt at the Vienna General Hospital which led to the creation of the sketch titled Gustav Klimt on his death bed,1918. It is a grotesque depiction of the deceased artist’s stroke and Flu ridden face.

Austrian painter Egon Schiele

The same year, Schiele began working on an oil painting titled Crouching Couple. Before he could finish the piece, his six-month pregnant wife succumbed to the Flu. Her unborn child did not survive either. The day before she died of the Flu, Schiele sketched a compelling portrait of his wife, Edith. Titled Portarit of the dying Edith Schiele, Edith’s face appears weary and emaciated.

Subsequently, the title Crouching Couple was changed to The Family. The picture depicts a man, woman and a child. The man beholds a listless gaze, one that consigns a melancholic otherness to him, as if he were not there. The woman reflects a cool resignation and looks towards her left. The child lies at the feet of the unclothed man and woman. It is tragic to know that only three days later, Schiele himself was taken by the Flu. The 27-year-old gifted artist’s life was untimely robbed of him by the virus. The Family, which is his last work, was acquired by the Belvedere Gallery in 1948 from Austrian avant-garde artist Hans Bohler. Bohler was a confidant to both Klimt and Schiele.

American photographer Alfred Stieglitz

In 1919, American artist Georgia O’Keeffe contracted a violent bout of the Flu in Texas. Her then lover and future husband Alfred Stieglitz captured a photograph of the artist and named it Portrait by Stieglitz in 1918. The photo was captured at a time when the pandemic was raging and O’Keeffe was in the middle of recovery. Stieglitz’s photo series on O’Keeffee is a romantic and artistic inroad into examining the effects of the virus on the body. The photograph is a triumph of the body-in-recovery over the harmful strain. The two lovers were enamoured of each other in the throes of a raging pandemic. However, Georgia’s recovery was peppered with episodes of extreme anxiety owing to her anti-war stance and ceaseless concern for her brother who was sent overseas to fight the War in France. Against the morbid backdrop of War and plague, O’Keeffee loved, hoped and defeated the virus.

The incoherence of this period was thoroughly exploited by the Dadaists. Poet Richard Hülsenbeck famously remarked that “Death is a thoroughly Dadaist affair.”

German artist George Grosz

Notably, Dada artist George Grosz painted The Funeral around 1918. The painting depicts mutilated faces of grotesque figures falling on one another in what appears to be a funeral procession. In a comment about his work, the artist stated “In a strange street by night, a hellish procession of dehumanized figures mills, their faces reflecting alcohol, syphilis, plague … I painted this protest against a humanity that had gone insane.” The artwork is emblematic of it’s unapologetic borrowing from Cubism and Expressionism while displaying the bleakness, cynicism and disquiet that pervaded the times. The reference to syphilis alludes to the rampant spread of venereal disease during the war. Soldiers and sex workers were at high risk as most transmissions occurred between them. A single sexual encounter could amount to gonorrhea and syphilis. Perhaps a certain preoccupation with death pervaded the artist’s mind. The recurrent theme of disease and mounting death toll finds expression in this painting.

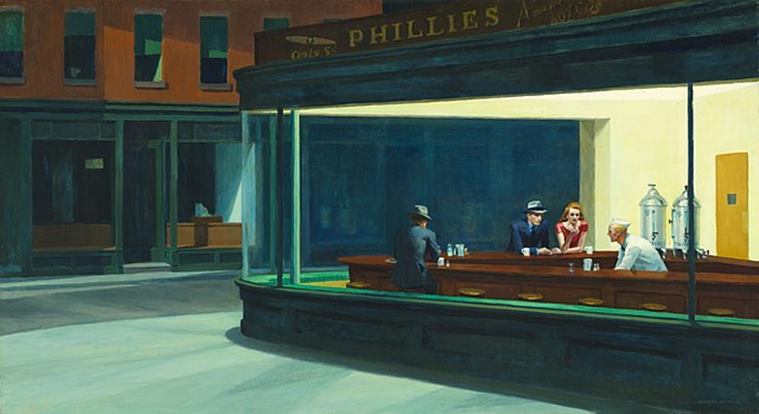

American painter Edward Hopper

During the onset of Covid-19 a succession of Edward Hopper paintings titled ‘We are all Edward Hopper paintings now’ flooded the internet. The succession of pictures meant for a cool joke is actually rather tragic. The pictures displayed lonely men at diners, bereft individuals in their desolate physically-distanced spaces, devoid of any tactile presences. Tracing Edward Hopper’s paintings back to the Flu epidemic, his famous works like Nighthawks, Cape Cod Morning and Chair Car embody the lockdown and social distancing norms of the Flu period.

Sigmund Freud

In 1920, Sigmund Freud’s daughter, Sophie died of septic pneumonia caused by the Flu. She was pregnant with her third child. In a letter to his mother Freud wrote:

“Dear Mother,

Yesterday morning our dear lovely Sophie died from galloping influenza and pneumonia. She is the first of our children we have to outlive. What Max will do, what will happen to the children, we of course don’t know as yet… But to mourn this splendid, vital girl who was so happy with her husband and children is of course permissible.”

After a few months, Freud’s wife Martha contracted the Flu. She however, recovered from it. After her recovery, Freud wrote to Karl Abraham “My wife as I can say is completely recovered…Who knows how many of us will survive the next winter, from which evil can be expected.’’

Three years after Sophie’s death, Sophie’s son, Hienle passed away. It is this child whose example Freud gives in his seminal essay on the death drive Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Following his grandchild’s death, Freud wrote to Ludwig Binswanger: “This child has taken the place of all my other children and grandchildren…since Hienle’s death, I no longer take care of my other grandchildren and no longer feel any desire to live.”

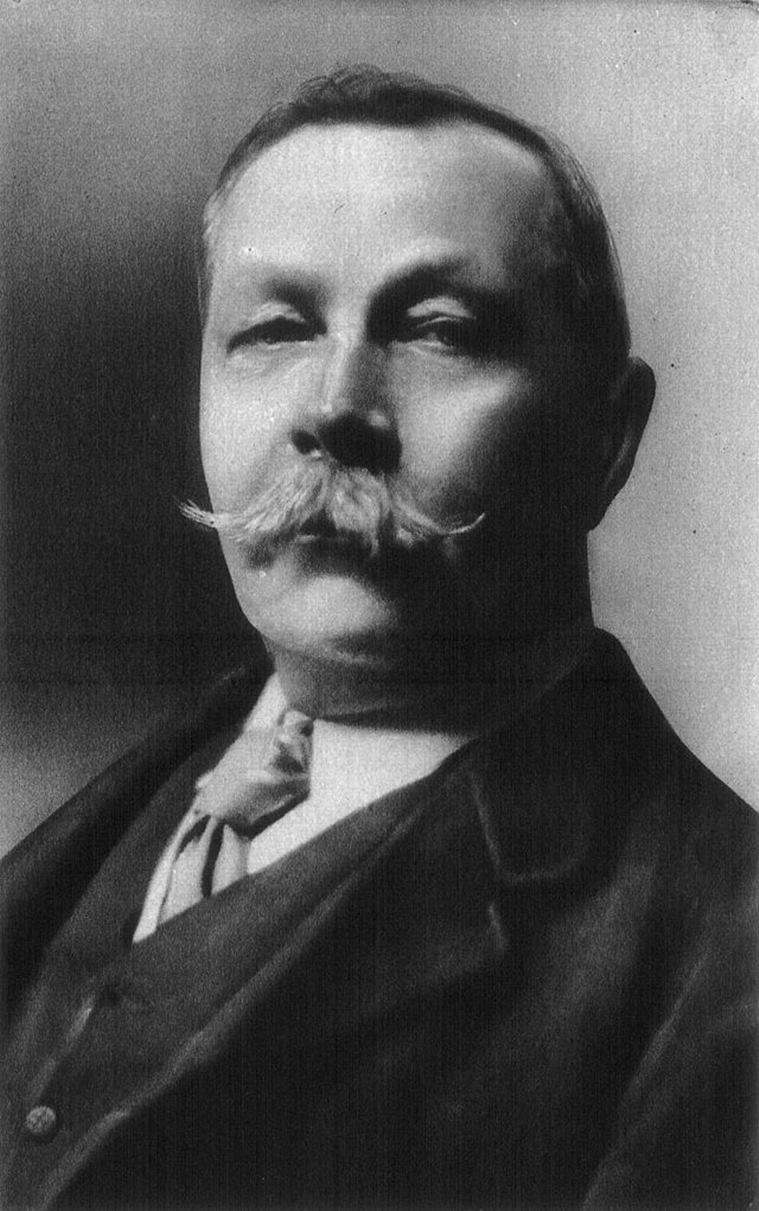

British writer Arthur Conan Doyle

In 1916, the prolific writer Arthur Conan Doyle’s son, Kingsley was deeply wounded while fighting the war in France. Consequently, he came down with the Influenza in one of the hospital camps and died of pneumonia induced by the strain in 1918. After losing his son, Doyle stopped writing fiction and leaned towards Spiritualism. He attended modern séances to communicate with his son. While on a lecture tour in 1922, Doyle told a reporter that, “I have many times spoken with my son.”

“You see, a so-called dead man goes to a happier plane,” asserted Doyle. “There is no crime, no sordidness, and it is many, many times happier.” Doyle also lost his younger brother to the Flu in 1919.

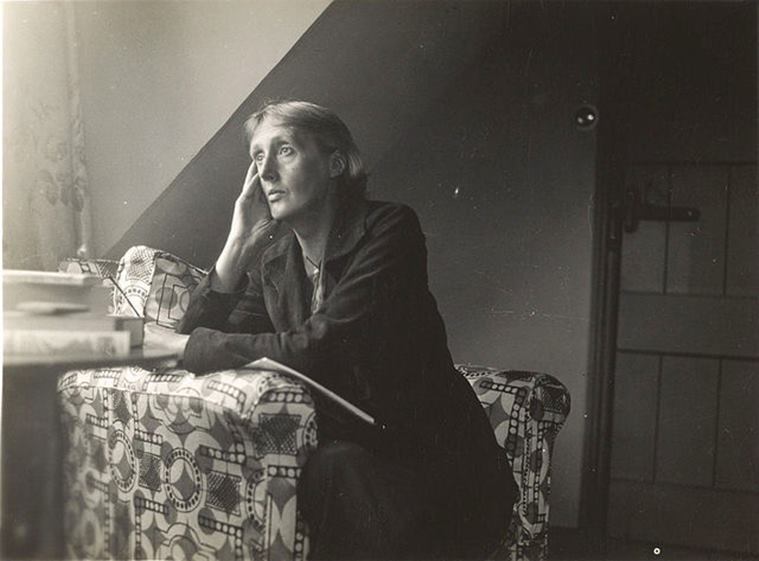

English writer Virginia Woolf

“Influenza, which rages all over the place, has come next door… Rain for the first time for weeks today and a funeral next door; dead of influenza,” wrote Virginia Woolf in her diary in 1918.

The writer had several bouts of the disease in 1918 and was advised bed rest for eight days. She also wrote an essay On being ill where she chronicles the mental effects of the disease.

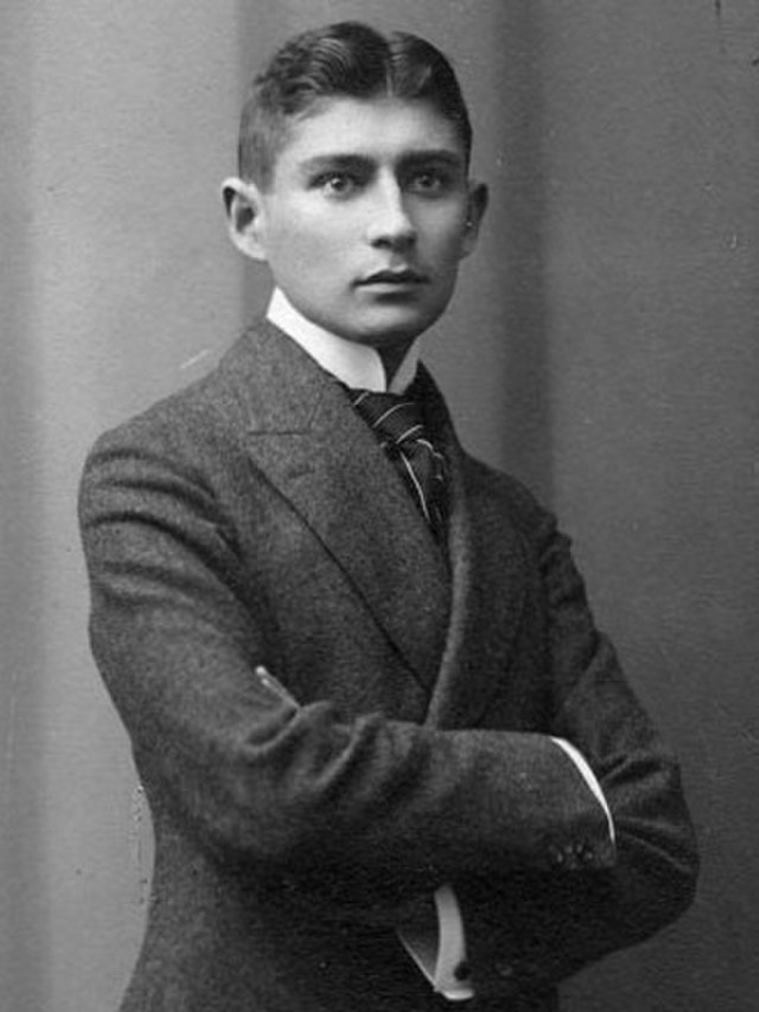

Bohemian novelist Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka contracted the flu in Prague in October 1918. From his sickbed he witnessed the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire through his window. “Getting the fever as a subject of the Habsburg monarchy and recovering from it as a citizen of a Czech democracy was certainly overwhelming, but also a little comical,” wrote his biographer.

The history of war and the history of disease are not parallel histories. They meander but they meet- in shared experiences, art and literature. Thereby promising an eternal presence in words and artistic expression.

Further Readings

Gay, P. (2009). Modernism: The Lure of Heresy. Vintage Books.

Bradbury, M (1991). Modernism. Penguin Books.

American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 187, Issue 12, December 2018, Pages 2561–2567

Freud, S (1920). Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Essay

Woolf, V (1926). On Being Ill. Essay.

Source: Read Full Article