In part II of ‘Foreign owners of Premier League clubs’, we explore if heavy investments by foreign owners have translated into on-field successes and how big money has opened up an ever-widening divide between the elite clubs and those at the bottom of the league.

While all foreign owners of Premier League clubs have not been able to bring about a radical transformation, the heavy investments made by Roman Abramovich and the Abu Dhabi United Group have certainly changed the fortunes of Chelsea and Manchester City.

The money that Abramovich pumped in transformed Chelsea into one of the most successful clubs in the Premier League. The Stamford Bridge club has won five Premier League titles, two Champions League titles and two Europa League trophies since the takeover. It also won the FA Cup five times and the League Cup thrice since 2003.

City’s is another story of remarkable transformation.

Between 1996 and 2003, relegations and promotions defined the story of City. After the Abu Dhabi Group took over in 2008, City’s first big splurge in the transfer market came two years later, as they spent £120 million on players, including David Silva, Yaya Toure and Mario Balotelli, in a single window. The next year, they signed Sergio Aguero for a reported fee of £38 million. The impact of the splurge was almost immediate—City handed Manchester United a derby day defeat with a scoreline of 6-1 in October, 2011 and went on to be crowned the Premier League champions at the end of the season.

Since then, City have won the Premier League four more times—in 2013, 2017, 2018 and 2020. This comes on the back of a £1.42-billion spending on transfers by the club in the last decade (2010-20), which is the highest in the Premier League. Chelsea were a close second, having spent just £41 million less than City during that period.

Third and fourth on the list were Manchester United and Liverpool, having spent £1.09 billion and £909 million respectively.

What does this say about inequalities between clubs in the Premier League?

Liverpool manager Jurgen Klopp recently said that the £305-million takeover of Newcastle by PIF is reminiscent of the now-discarded idea of building a Super League. “What will it mean for football? A few months ago we had an issue with clubs building a Super League, and rightly so. But this is building a super team, guaranteed places in the Champions League in a few years,” Klopp was quoted as saying by Sky Sports News.

He added, “Newcastle fans will love it, but money doesn’t buy success. They have money to make mistakes, but they will be where they want eventually.”

Football’s embracing of hypercapitalism has led to a disproportionate concentration of financial resources in the hands of a few, with the gap between the six “super clubs” and the rest ever widening in the Premier League.

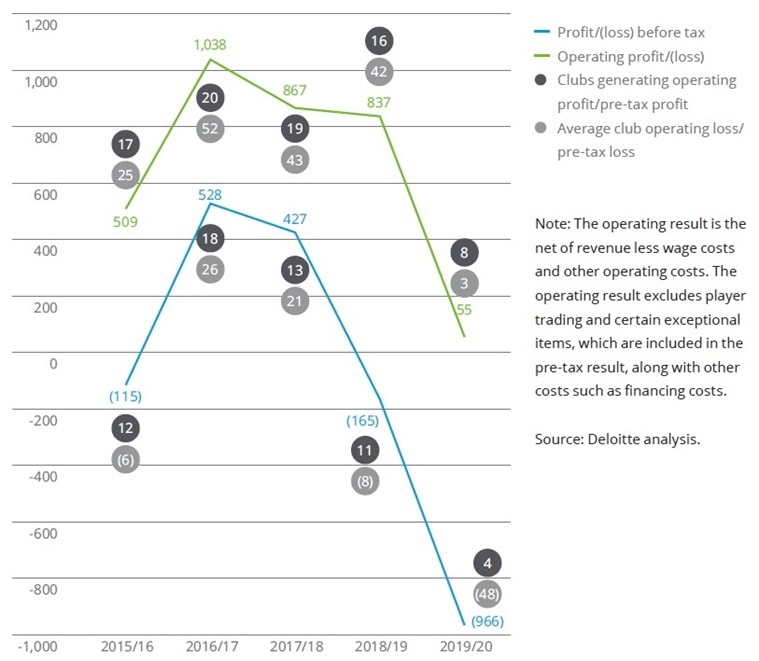

It is important to consider some hard data to put things into perspective. Even after a year when finances of Premier League clubs plummeted after the pandemic—there were aggregated pre-tax losses of £966 million across the 20 Premier League clubs—Manchester City spent £100 million on Jack Grealish and Chelsea £97.5 million on Romelu Lukaku in the summer transfer window this season. These transfer fees are more than the entire revenue of AFC Bournemouth (£95 million) for the 2019-20 season.

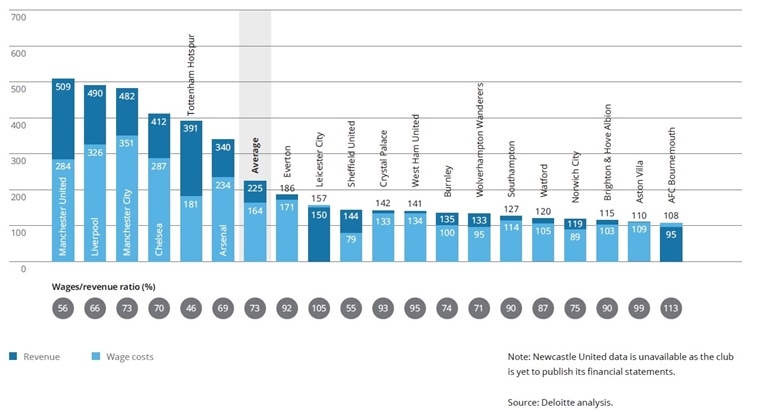

According to the Deloitte Annual Review of Football Finance 2021, Manchester United had the highest revenue for 2019-20 (£509 million), followed by Liverpool (£490 million), Manchester City (£482 million), Chelsea (£412 million), Tottenham Hotspurs (£391 million) and Arsenal (£340 million). The difference in revenues with the three clubs which got relegated shows how big the chasm is—Norwich City, Brighton and AFC Bournemouth recorded revenues of £119 million, £115 million and £95 million respectively. The wage to revenue ratio is also a fair indicator of how hard bottom clubs have to strive to make ends meet and compete against those with deep pockets—while the ratio was 56% for Manchester United, it was 99% for Aston Villa and 113% for Bournemouth.

The gap between the wealth of the “big six” clubs and the rest of the Premier League is only going to increase further, the report states. One important contributory factor to this is the big television money that comes in with qualifying for the Champions League or the Europa League—presence or absence of European football can hugely alter a club’s finances in any given season.

Outlandish spending in the transfer market—PSG signing Neymar and Kylian Mbappe in 2017 being a case in point—have rekindled the criticism that Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations actually “protect” the elite clubs. Or some of them find ways to get around the rules.

According to a report in the Daily Mail, a leaked trail of emails showed that Manchester City illegitimately inflated their income in a bid to flout FFP rules. The suspicion was that City used companies owned by their state-funded group to sponsor their shirts and income, thereby vastly inflating their income. This, in turn, allowed the Abu Dhabi state to pump more money into the club. Following further investigations which cast a shadow over City’s financial dealings, the club was handed a two-year ban by UEFA in 2019 for “serious breaches of cost-control regulations”. But the Court of Arbitration of Sports later overturned the ban citing “insufficient conclusive evidence”.

The bottom line is stark—every time De Bruyne threads through a silken pass to Gabriel Jesus or Mbappe wriggles past defenders, it is difficult to not let the joy of the moment be adulterated with the acknowledgment of the financial inequalities that are at play.

La Liga president Javier Tebas recently said that clubs like Manchester City and Paris Saint-Germain are guilty of “financial doping” due to “oil or gas money”. “The prices that are spoken of over certain players are very difficult to pay except the state-owned clubs like PSG and Man City that sign with oil or gas money. They are the only ones that could do such operations in a tricky way. There is €8,000m less in the market. I see that a PSG or City appears (spending money) because of their financial doping, but not in the rest of the teams,” Tebas was quoted as saying by Marca.

At the other end of the spectrum is an incident which was bemoaned by many fans as a “football tragedy”—FFP regulations meant Messi had to leave Barcelona for PSG earlier this year. The Catalan club wanted to extend the six-time Ballon d’Or winner’s contract but La Liga rules and FFP limits proved a hindrance—with Messi on board, the club’s wage-to-turnover percentage would have been 110 per cent.

Barcelona’s debt now stands at more than $1 billion, with the club having landed in financial trouble on the back of a reckless splurge and disastrous policy in the transfer market. After selling Neymar for €220 million in 2017, the club went on to pay €105m up front, plus €42m in bonuses for Ousmane Dembélé (reportedly after ignoring the opportunity to sign Mbappe), €160m for Philippe Coutinho, €75 for Frenkie de Jong and €120m for Antoine Griezmann.

By 2020, Barcelona were in deep financial trouble, with the club having spent €1 billion on transfers between 2014 and 2019. This eventually saw the departures of Luis Suárez, Griezmann and Messi.

Has there been any pushback against the super-rich owners?

The most significant pushback in recent times came after the elite clubs from across leagues sought to come together to form the breakaway Super League. The top Premier League clubs were rocked by heavy backlash from fans, with vitriolic rage directed at the owners. After the ESL plans were abandoned, many of the owners, such as Liverpool owner John Henry, Manchester United co-chairman Joel Glazer and Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich, apologised to fans. Many players also came out with statements against the Super League.

More recently, the hostility against Newcastle’s takeover by PIF brought together all the other 19 Premier League clubs. In a special meeting, they voted to prevent the Saudi owners from striking lucrative sponsorship deals. The proposed legislation, which temporarily bans commercial arrangements that involve pre-existing business relationships, had 18 votes in its favour. Newcastle voted against it while Manchester City abstained from exercising its choice. Most of the clubs see the proposed rule change as a safeguard against Newcastle gaining an unfair advantage with the help of deals in the oil-rich Saudi kingdom.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

The pushback is understandable. How City went on a big spending spree since being bought by Sheikh Mansour in 2008 even as it struck deals with companies linked to the emirate is in public knowledge. In keeping with the Premier League’s rules, Newcastle can spend more than £150m on signings the next year, starting from the January transfer window.

The home match against Tottenham Hotspur was the first since Newcastle’s takeover by PIF. There were fan protests outside the stadium. A van went around with a poster that read “Jamal Khashoggi Murdered 2.10.18”. A Spurs fan carried a message saying Suhail al-Jameel—a gay man reportedly imprisoned in Saudi Arabia for posting a shirtless photo—should be freed.

But inside the stadium, there was an air of jubilation as fans in Middle Eastern long robes and headdresses danced in the stands. The club in a statement later said, “No one among the new ownership group was in any way offended by the attire of the fans who chose to celebrate in this way…However, there remains the possibility that dressing this way is culturally inappropriate and risks causing offence to others.”

Source: Read Full Article