Pakistan had stopped all trade with India in protest against the August 5, 2019 changes in Jammu and Kashmir. It had also said it would not be sending a High Commissioner to New Delhi; in retaliation, India had withdrawn its High Commissioner in Islamabad.

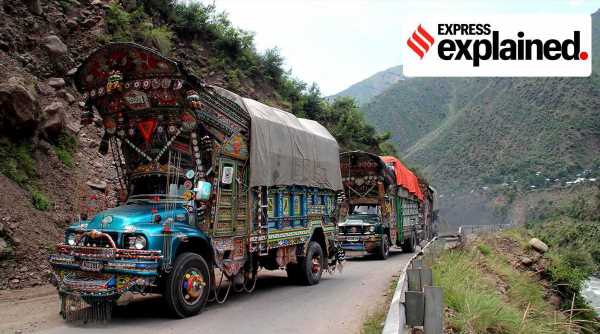

The reopening of trade at Wagah for cotton and sugar exports from India to Pakistan after two years is among the first substantive relaxations in bilateral ties following the February 25 restoration of the ceasefire at the Line of Control.

Pakistan had stopped all trade with India in protest against the August 5, 2019 changes in Jammu and Kashmir. It had also said it would not be sending a High Commissioner to New Delhi; in retaliation, India had withdrawn its High Commissioner in Islamabad.

In recent days, Pakistan had signalled a softening of its stand that it would not talk to India before a full rollback of the changes in J&K. Although both India and Pakistan were cautious not to link their reaffirmation of the ceasefire to any wider improvements in ties, it had been apparent that a backchannel process had been at work, and that the ceasefire was likely the first step towards other moves to normalise ties.

There have been indications that trade ties would be the easiest to normalise. Over the last few months, there has been pressure from the Pakistan textile lobby for resuming import of Indian cotton yarn. On Wednesday, cotton prices in Pakistan touched a 11-year-high of Rs 11,700 per maund, Dawn reported. Prices have been rising due to a steep fall in cotton yields in Pakistan. Pakistan has also allowed private traders to import up to 0.5 million tonnes of white sugar from India.

Generals’ different strategy

The Pakistan military establishment, the power behind Imran Khan’s civilian government, is certainly signalling a “rational” shift in the way it views relations with India, and the rest of the region and the world. Army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa said recently that Pakistan had rethought its national security paradigm from purely military defence to economic security.

Underpinning this review of national security, said Bajwa in a landmark speech in Islamabad, was “our desire to change the narrative of geo-political contestation into geo-economic integration”.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

The rethink coincides with fresh troubles for Pakistan’s financial assistance-dependent economy. The sweeping changes in West Asia, especially after the Abrahamic accords, have left Pakistan isolated among countries that it saw as “brothers” who would help out now and then with a moratorium on payments for oil, or a loan on easy terms. But Saudi Arabia and UAE have been talking tough with Pakistan in recent months. China has rescued it a couple of times, but Pakistan is as wary of borrowing too much from Beijing as others in the region.

An IMF loan with tough conditions has helped the country stay afloat but has not made the government popular. Earlier this week, Pakistan received a tranche of $500 million of the $6 billion loan, which had been on hold since February 2020 pending decisions that it has now taken, such as increases in electricity tariff, freeing the central bank from government control, and withdrawal of income tax exemptions.

Pakistan has always viewed itself as a “special” country because of its location at an important crossroads between Asia and Eurasia. It has believed this could help achieve its strategic objectives in the region and beyond.

But the realisation that location could be used to Pakistan’s economic benefit was clearly not actionable until the military establishment got on board the idea.

During Gen Pervez Musharraf’s decade-long rule, there was some experimenting with connectivity; the Iran-Pakistan-India oil pipeline was perhaps the earliest effort. New Delhi was a hesitant participant, and threatened to pull out over transit fees that Pakistan was negotiating. The project turned a non-starter after the 2008 Mumbai attacks. By then, India had signed the nuclear deal with the US. Pakistan alleged that the Indian pullout was under US pressure. Efforts to get a bilateral Iran-Pakistan pipeline going are yet to bear fruit.

All through this time, Pakistan has denied India transit rights overland for trade with Aghanistan due to security and economic concerns, while granting Afghanistan limited transit rights for export of dried fruit to India. This Afghan-India trade has continued even through the last two years.

The answer to whether the decision by the government in Islamabad to set Kashmir aside and start trade with India is a strategic shift lies in how ready Pakistan’s generals are to put their money where their mouth is on connectivity and “geo-economics”, and grant India overland rights to trade with Afghanistan.

New Delhi has for years pushed the India-China model of bilateral relations, where trade has taken the front seat and the contested boundary is the subject of long-drawn negotiations. If Pakistan is beginning to see it this way too, that would indeed be a huge change.

Untapped potential

Trade between India and Pakistan has always been hostage to their hostile relationship. For years, Pakistan traded with India on the basis of a positive list, changing to a negative list only in 2009. Other efforts to ease trade have been unsuccessful, including a 2011 push by Pakistan to reciprocate India’s grant of MFN. It came a cropper on a campaign by Hafiz Saeed, head of the LeT/JuD to portray that this was a huge concession to India. His translation of MFN into Urdu — sabse pasandeeda mulk — rattled Islamabad.

India withdrew MFN status to Pakistan after the Pulwama attack. It has to be seen whether the two countries will grant each other this status, which is a WTO obligation. In the first few years of the last decade, the move to relax the visa regime for businessmen did not go far.

While the total value of bilateral trade has hovered around $2 billion, unofficial trade through third countries such as UAE is valued at far more.

Trade numbers have been next to non-existent since August 2019. The beneficial impact of even limited trade resumption will be felt on both sides.

Source: Read Full Article