‘The war of 1962 exposed the hollow intellectual foundations of Nehruvian foreign policy, especially vis-à-vis China and that is why it was such a shock.’

After the December 9, 2022 clash between Indian and Chinese troops in Tawang, the Opposition, led by the Congress, criticised Prime Minister Narendra Modi, saying his government is ‘putting the country in danger’.

Not surprisingly, the government responded by invoking the 1962 War and the then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

The Bharatiya Janata Party declared this is not ‘Nehru’s India, who lost 37,242 square km to China while sleeping’.

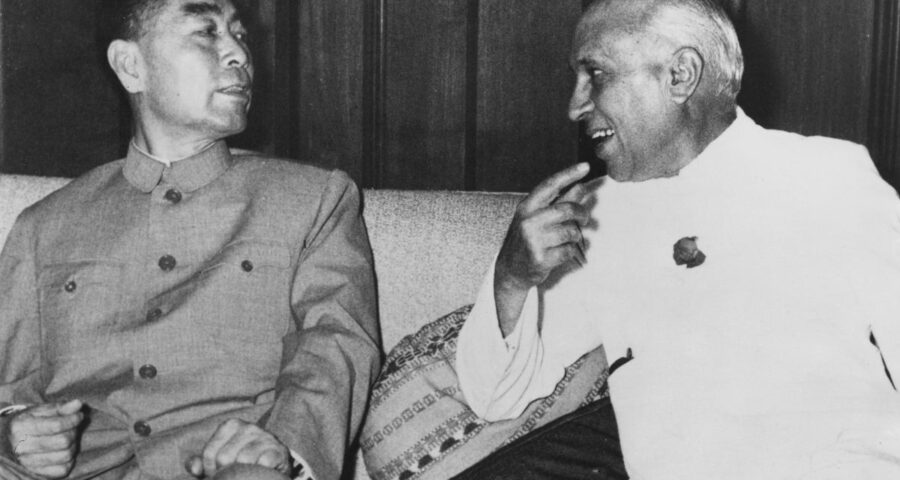

Those who blame Nehru for the downturn India-China ties took after the ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai‘ years, often cite Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s letters to the then PM, warning him against trusting an expansionist China and build military strength to meet the challenge it posed, especially after its annexation of Tibet in 1951.

In their book Nehru: The Debates that Defined India, authors Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain tried to offer a way to understand the mind of India’s first prime minister through the debates that he had with his contemporaries, including Patel.

The book deals with Patel’s correspondence with Nehru on the China question, and calls the latter’s approach towards China as ‘supine’.

In Part 2 of their interview with Rediff.com‘s Utkarsh Mishra, Singh and Hussain said, “To say that India’s policy in the early 1950s was not supine is a negation of both fact and contemporary opinion.”

- Part 1: ‘Nehru profoundly misunderstood how important religion was in the lives of the people’

What I got from the correspondence between Nehru and Sardar Patel on the Chinese question was that they both agreed on the nature of the problem, however, they had different ideas about how to deal with it. Do you agree?

Nehru was not wrong in saying that preparing for war with China in 1950 would cost India dear in its formative years. Nevertheless, he also agreed that preparations should be made for securing India’s frontiers in the North and North East. And he also made a distinction between these two preparations.

How do you see these developments from 1950 to the 1962 War?

Tripurdaman Singh: I don’t think they agreed on the nature of the problem at all. Nehru conceptualised postcolonial India’s position in the world very differently from Patel. The costs of preparing for a showdown with China, for Nehru, were not simply material; they were also ideational.

They involved closer ties with the West, abandoning India’s attempt to play a leading role in Southeast Asia as the pre-eminent socialist and anti-colonial force, giving credence to Sino-Soviet charges of Nehru and India being the front paw of Anglo-American machinations, undermining Nehru’s credentials as a great socialist statesman.

Patel’s position also involved India embracing its status — political and legal — as a successor to the Raj (with its attendant claims and responsibilities) rather than seeking to largely shed its colonial heritage and take on the mantle of socialist internationalism as Nehru wanted.

The distinction you identify didn’t really exist in practice since Nehru believed socialism meant peace and therefore no war with China was ever possible.

Preparations were minimal, predicated on precluding the possibility of war altogether. And we know how that ended.

Nehru himself pronounced judgement: We were living in a world of our own imagination…

While Nehru’s statements on Tibet do reflect that India abandoned a friend that looked up to it, is it appropriate to call the entire policy towards China ‘supine’?

India did provide shelter to the Dalai Lama and Tibetan refugees. Also, in subsequent years, India did try to formalise its borders with China while China kept dilly dallying.

Aren’t there records of India rejecting Chinese interpretations of the boundary and China issuing clarifications about them during these years?

Singh: By the time India provided shelter to the Dalai Lama and Tibetan refugees, it had already supported China in militarily occupying Tibet and then helped China legitimise its occupation.

It had opposed Tibetan attempts to raise the issue at the United Nations and American efforts to arm the Tibetans. Sino-Indian relations had already nosedived and there was tremendous public sympathy in India for the Dalai Lama in 1959.

To say that this proved India’s policy in the early 1950s was not supine is a negation of both fact and contemporary opinion. It is important to see that the policy was also considered supine at the time by many seasoned contemporary observers, including figures like Patel and (Chakravarti) Rajagopalachari.

Now there were many reasons, some even reasonable, for policy to evolve as it did, and we go over them in the book. But to say later rejections of Chinese demands, after allowing them to gain tremendous strategic advantage — in pursuit of self-imposed ideological preconditions — negates what was happening in the early 1950s wouldn’t be correct.

Nehru’s views on China seem to be rooted not in his internationalism, but in his Pan-Asianism and a deep distrust of the West.

How did Nehru, who always cherished Western democracies and who even supported the Allies in their war against fascism when India was itself under the yoke of one of them, come to distrust the Western powers?

Was it a result of their attitude towards the Kashmir issue and their whole-hearted support to Pakistan?

Singh: I don’t think Nehru ever really cherished Western democracies. He actively disliked America. One mustn’t read all that much into his support for the Allies in the war. It was the default position for most reasonable people.

Apart from outliers like (Subhas Chandra) Bose, no one really wanted a world ruled by Hitler or an India ruled by Japan. Plus, Nehru was closely tied to socialist circles in Britain and Europe, who were uniformly anti-fascist.

I think that several things went into the making of his distrust of the West. Partly, of course, it is explained by Western colonialism and the crucible of anti-colonial politics he emerged from. Here the West was a natural enemy.

But more so, he wanted to negate Sino-Soviet charges of being a Western stooge and be a leading proponent of anti-colonialism and socialist internationalism on the world stage — the big brother leading the smaller brothers of Southeast Asia towards freedom and socialism.

These necessarily implied distancing himself from the West.

Adeel Hussain: Nehru’s early political years were spent fighting Western colonialism. So there was always an element of distrust in his politics towards liberal democracies that had upheld or quietly accepted colonialism.

His brief strategic alignment with the British government to fight fascism was born out of necessity — not out of trust.

After Independence, Nehru was worried that other Asian powers would not accept India as a full sovereign country but would continue to see it under the influence of Western powers.

This thinking may explain why Nehru largely rejected any close association with Western powers as prime minister.

In his letters of 1950, Nehru contemplated a World War if China attacks India. However, when the war did happen in 1962, India didn’t get any support even from its trusted friends. Does it bring into question Nehru’s understanding of then world politics?

Singh: It does. He himself said after the war that he had been living in a world of his own imagination.

During the war he wrote to (American) President (John F) Kennedy and requested the United States for military assistance, going so far as to ask for American bomber squadrons to bomb China — at a time when the US and the Soviet Union were close to potential nuclear war over the Cuban missile crisis.

The war of 1962 exposed the hollow intellectual foundations of Nehruvian foreign policy, especially vis-à-vis China and that is why it was such a shock. It broke Nehru.

Source: Read Full Article