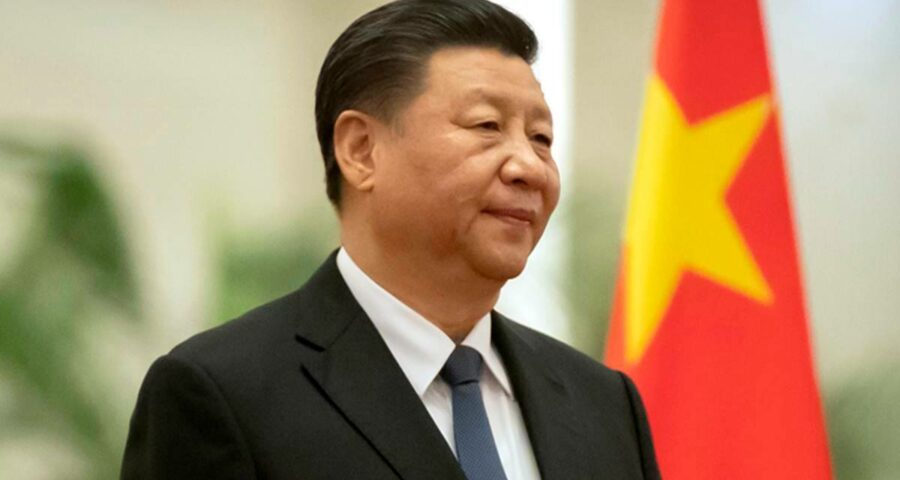

Chinese President Xi Jinping's expected absence from the talks could indicate that the world's biggest CO2 producer has already decided that it has no more concessions to offer at the UN COP26 climate summit in Scotland after three major pledges.

The leaders of most of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters gather in Glasgow from Sunday, aiming to thrash out plans and funds to tilt the planet towards clean energy. But the man running the biggest of them all likely won’t be there.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s expected absence from the talks could indicate that the world’s biggest CO2 producer has already decided that it has no more concessions to offer at the UN COP26 climate summit in Scotland after three major pledges.

Instead, China will likely be represented by vice-environment minister Zhao Yingmin along with the veteran Xie Zhenhua, who was reappointed as the country’s top climate envoy earlier this year following a three-year hiatus. “One thing is clear,” said Li Shuo, senior climate adviser with Greenpeace in Beijing. “COP26 needs high-level support from China as well as other emitters. “The head of the world’s third-biggest source of climate-warming emissions, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has committed to attending the COP26 summit, which runs from Oct. 31 to Nov. 12.

Like other leaders, he will come under pressure from summit organisers to commit to quicker emissions cuts and set a target date to reach carbon neutrality – a target set by Xi for 2060 in a surprise move last year.

But China will be unwilling to be seen yielding to international pressure for more ambitious goals, according to one environmental consultant, especially as it grapples with a crippling energy supply crunch at home.

Beijing is “already maxed out”, said the consultant, speaking on condition of anonymity citing the sensitivity of the matter.

Though there has been no official announcement, analysts and diplomatic sources said few had been expecting Xi to attend COP26 in person. He has already missed several high-profile global summits since the COVID-19 outbreak began in late 2019, and didn’t physically attend the Global Biodiversity Conference in China’s Kunming earlier this month.

They also said Xi was unlikely to lend his physical presence – a virtual video appearance remains a possibility – to a meeting that had little prospect of any significant breakthrough, especially after China brushed off U.S. attempts to treat climate as a ‘standalone’ issue that could be separated from the broader diplomatic disputes between the two sides.

Rather than making more concessions, China and India’s top priority is to secure a strong financing deal allowing richer countries to meet their Paris Agreement commitment to provide $100 billion per year to help pay for climate adaptation and transfer clean technology in the developing world. Xi did attend the Paris summit in person in 2015.

DOMESTIC CONCERNS

Although Xi has not travelled outside China since before the pandemic, he has made three major climate announcements on the international stage. His unexpected net zero commitment came in a video address to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in September 2020. That announcement encouraged enterprises, industry sectors and even other countries to respond with their own net-zero action plans.

Xi also said in a message to the US-led Leaders’ Summit on Climate in April that China would start cutting coal consumption by 2026. And he used this year’s UNGA to announce an immediate end to overseas coal financing, a major bone of contention.

Like India, China has been under pressure to add more ambition to its updated “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) on climate change, which are due to be announced before the Glasgow talks begin.

However, the revisions are expected to focus on implementing the targets that have already been announced, rather than making them more ambitious.

China has repeatedly stressed that its climate policies are designed to serve its own domestic priorities, and will not be pursued at the expense of national security and public welfare.

Ma Jun, director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, a Beijing-based non-government group that monitors corporate pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, said China already had enough climate challenges to deal with and has little leeway to go further in Glasgow.

“With all the headwinds and all the pledges that have been made, it is important to take stock and consolidate,” he said. “It’s not enough to put these (commitments) on paper,” he added. “We have to translate them into solid actions.”

Source: Read Full Article