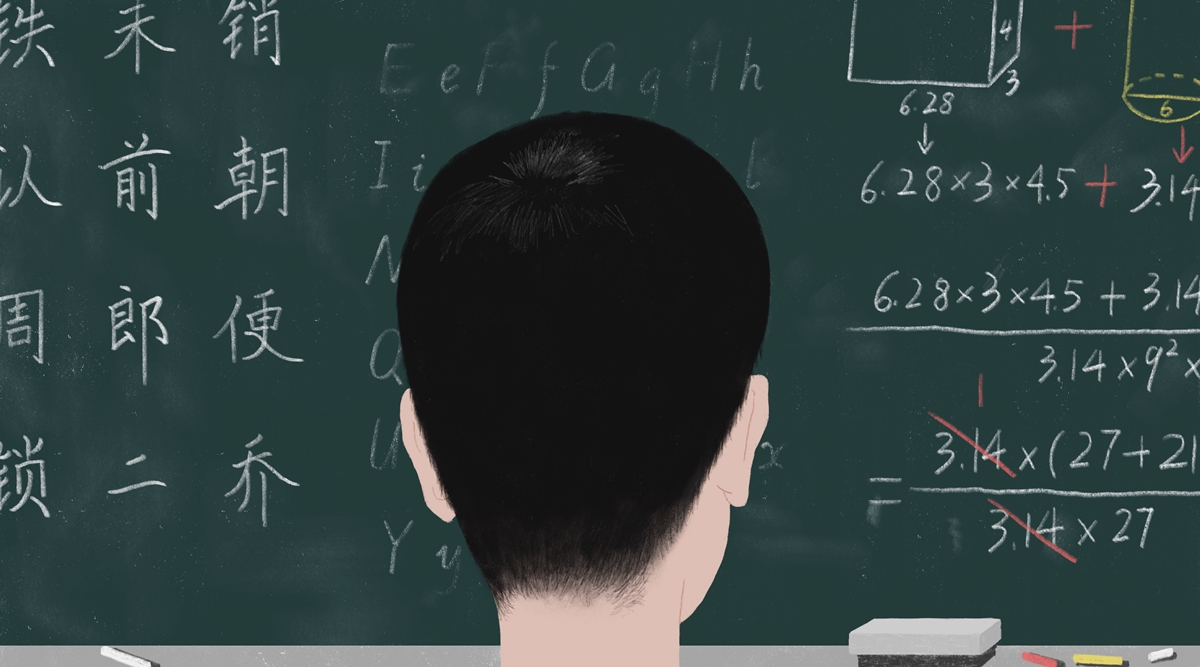

Education authorities in Shanghai, the most cosmopolitan city in the country, last month forbade local elementary schools to hold final exams on the English language.

By Li Yuan

As a student at Peking University law school in 1978, Li Keqiang kept both pockets of his jacket stuffed with handwritten paper slips. An English word was written on one side, a former classmate recalled, and the matching Chinese version was written on the other.

Li, now China’s premier, was part of China’s English-learning craze. A magazine called Learning English sold a half-million subscriptions that year. In 1982, about 10 million Chinese households — almost equivalent to Chinese TV ownership at the time — watched “Follow Me,” a BBC English-learning program with lines like, “What’s your name?” “My name is Jane.”

It is hard to exaggerate the role English has played in changing China’s social, cultural, economic and political landscape. English is almost synonymous with China’s reform and opening-up policies, which transformed an impoverished and hermetic nation into the world’s second-biggest economy.

That is why it came as a shock to many when education authorities in Shanghai, the most cosmopolitan city in the country, last month forbade local elementary schools to hold final exams on the English language.

Broadly, Chinese authorities are easing the workloads of schoolchildren amid an effort to ease the burdens on families and parents. Still, many Chinese people with an interest in English cannot help but see Shanghai’s decision as pushback against the language and against Western influence in general — and another step away from openness to the world.

Many call the phenomenon “reversing gears,” or China’s Great Leap Backward, an allusion to the disastrous industrialization campaign of the late 1950s, which resulted in the worst man-made famine in human history.

Last year, China’s education authority barred primary and junior high schools from using overseas textbooks. A government adviser recommended this year that the country’s annual college entrance examination stop testing English. New restrictions this summer on for-profit, after-school tutoring chains affected companies that have taught English for years.

Original English and translated books are discouraged at universities, too, especially in the more sensitive subjects, such as journalism and constitutional studies, according to professors who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Three of them complained that the quality of some government-authorized textbooks suffered because some authors were chosen for their seniority and party loyalty instead of their academic qualifications.

The president of prestigious Tsinghua University in Beijing came under fire this summer after sending each new student a Chinese-language copy of Ernest Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea.” He wrote in a letter that he wanted the students to learn courage and perseverance. Some social media users questioned why he would choose the work of an American author or why he did not encourage the students to study for China’s rise.

In some cases, Communist Party orthodoxy is replacing foreign texts. Elementary schools in Shanghai may not be conducting English tests, but a new textbook on “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism With Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” will be required reading in the city’s elementary, middle and high schools starting this month. Each student is required to take a weekly class for a semester.

The Communist Party is intensifying ideological control and nationalistic propaganda, an effort that could turn the clock back to the 1950s and 1960s, when the country was closed off to much of the world and political campaigns overrode economic growth. A nationalistic essay widely spread last week by Chinese official media cited “the barbaric and ferocious attacks that the U.S. has started to launch against China.”

Even just a few years ago, the Chinese government still emphasized learning a foreign language. “China’s foreign language education can’t be weakened. Instead, it should be strengthened,” wrote the Communist Party’s official newspaper, People’s Daily, in 2019. The article said nearly 200 million Chinese students took foreign language classes in 2018, from elementary schools all the way to universities. The vast majority of them were learning English.

For a long time, the ability to read and speak English was considered a key to well-paying jobs, study-abroad opportunities and better access to information.

When Li studied law in Beijing in the late 1970s, the country had just emerged from the tumultuous Cultural Revolution. He and his classmates wanted to learn Western laws, but most of the books were in English, said Tao Jingzhou, Li’s college classmate and a lawyer in Beijing now. Their professors encouraged them to learn English and translate some original works into Chinese.

Li became part of a group that translated the book “The Due Process of Law,” by Lord Denning, the British jurist.

In the 1980s and 1990s, young Chinese in many cities congregated at “English corners” to speak a foreign tongue to one another. Some brave ones, including future Alibaba founder Jack Ma, struck up conversations with the few English-speaking foreign visitors to improve their conversational skills.

As the internet developed, a generation of Chinese learned English from TV series like “Friends” and “The Big Bang Theory.”

Some businesspeople struck gold by teaching English or offering instruction on how to take tests in the language. New Oriental Education and Technology, a company based in Beijing, became such a cultural phenomenon that it inspired a blockbuster film, “American Dreams in China.” The hero taught English the way many in China learned it, such as memorizing the word “ambulance” as the Chinese for “I can’t die.” (“Au bu neng si.”)

China’s top leaders used to pride themselves on their English. Former President Jiang Zemin recited Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in his 2000 interview with “60 Minutes” and told aggressive Hong Kong journalists that their questions were “too simple, sometimes naive.” As recently as 2013, Li delivered a speech partly in English in Hong Kong.

English lost some of its sheen after the 2008 financial crisis. Xi Jinping, China’s paramount leader, does not appear to speak it.

Now English has become one of the signs of suspicious foreign influence, a fear nurtured by nationalist propaganda that has only worsened in tone since the outbreak of the coronavirus. As a result, China’s links to the outside world are being severed one by one.

China’s border control authority said in August that, as part of pandemic control procedures, it would suspend issuing and renewing passports except for urgent and necessary occasions. Middle-class Chinese citizens with expired passports wonder whether they will be able to travel abroad even after the pandemic.

Some residents in the eastern city of Hangzhou who received phone calls from abroad immediately got calls from the local police, who asked whether the calls were scams. Scholars and journalists who participated in an exchange program sponsored by the Japanese Foreign Ministry were called traitors and urged to apologize in early summer.

For Chinese people trying to keep their connections abroad, it may feel like the end of an era. Share prices of New Oriental, the education giant, tanked in July after the Beijing government announced crackdowns on after-school tutoring services. The Shanghai government’s announcement drew praise online from some nationalistic quarters.

But as long as China does not shut its door to the outside world, English will still be viewed by many as crucial toward unlocking success. After the Shanghai announcement, an online survey with about 40,000 responses found that about 85% of respondents agreed that students should continue to learn English no matter what.

COVID-19 and tensions between the two countries have hurt the flow of Chinese students into U.S. universities. Still, the U.S. Embassy in Beijing said it had issued 85,000 student visas since May.

A lawyer in Shanghai with a nationalistic bent wrote on his verified Weibo account that he would like his daughter to learn English well because English would be helpful for China’s economic growth.

“When could Chinese stop learning English?” he asked, then answered his own question: When China becomes a leader in the most advanced technologies and the world needs to follow it.

“Then,” he wrote, foreigners “can come to learn Chinese.”

Source: Read Full Article