Doctor G is outwardly all for women, but evidently has no interest in them, observes Sreehari Nair.

Anyone who believes that the world would be a better place if it were run by women clearly hasn’t peeked into the ladies compartment of a Mumbai local train. Oh, the tribal rites on display there!

I once saw a gang of office-bound ladies in prim attire acting like self-appointed ticket examiners and hauling over the coals a fisherwoman, who kept up a verbal battle for three consecutive railway stations before producing in a moment of pure Koli swagger her first class pass.

I have heard an argument between two dames flare up into shouts of “Beeetch! Beeetch!” to which a third dame, a mere bystander with a pink stole draped around her neck, responded with a smirk: “Beach? Which beach are they talking about?”

I have been witness to vicious catfights complete with scratching, smacking, hair-pulling, pinching, and more — most of these arising out of debates about the relevance or growing irrelevance of the ‘fourth seat’.

In any of these ladies compartments, so chock-full that everybody is elbow to rib and haunch to paunch, you would find as many brawlers, punters, fixers and detached dopey souls as you would find in a gents compartment of the same local train.

Call me excessive, but I feel very much like a rookie sociologist while walking away after one of those gentle peeks.

They are my humanity baths, if you will. And it’s probably because of such vivid everyday experiences — which allow me to preview a wide range of personality-types in a relatively short span of time — that I couldn’t take seriously a single minute of Ayushmann Khurrana’s latest attempt at remorse and repentance, Doctor G.

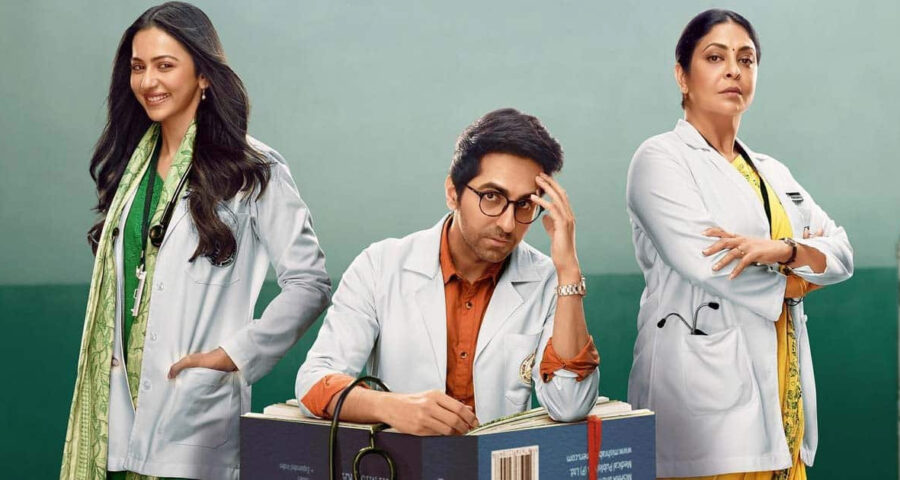

Going in, you might think that the most annoying aspect of Anubhuti Kashyap’s film would be its insistence on echoing all those motifs that one has come to readily associate with a ‘project’ starring Ayushmann Khurrana: This time around he is made up as Uday, a medical student who is stuck with a seat in the gynecology department of a government hospital in Bhopal, and who in practically every reel is coached and coached about how to become a better man to the ladies.

But even as Uday’s arc turns out to be as depressing and facile as you feared it might be, Doctor G rings especially hollow when you turn your attention from the ‘coachee’ to the ‘coaches’.

It’s then that you realise there’s no individuality whatsoever about the women in this film.

Yes, the biggest bummers in Doctor G are its female characters, who have nothing to do except play Sensei to Uday and aid him in his process of awakening.

It’s all very ‘technical’, you see: For when you get so high on cleaning up men, why would you stop to check if there are any personality differences that separate one woman in your film from another? That would simply be inconvenient, I suppose.

So everybody from Rakul Preet Singh’s Dr. Fatima (with a carefully chosen nose ring) to Priyam Saha’s Dr Jenny (with an attitude as balmy as sandpaper) is pitched at the same level of ‘divinities waiting to be understood by men’. Oh, how I missed my humanity baths!

To be fair to the cast it’s the characterisations that are limp, and among the actors there are two who offer you glimpses of possessing a life beyond the story-arc they find themselves in.

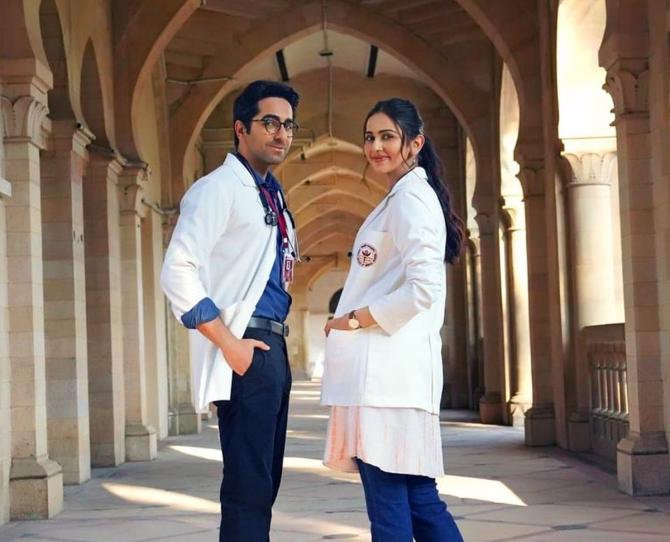

To begin with there’s that sorceress-genius, Sheeba Chaddha, who mercifully dials down the fanatical narrative at various points, and makes you appreciate the decor and lightings of her rather spontaneous house as well as the slowly settling smog of a Bhopal night, and in one rollicking scene, even hands out the silkiest slap in the history of Indian Cinema (That chamaat got the longest laugh in the theatre I was in).

Aside from Chaddha, the only performer who makes any impression is 26-year-old Ayesha Kaduskar, passing off as a teenager without the slightest sweat, walking that tightrope between grouchy-cute and can-light-up-any-dead-setting luminous.

The characters played by Ayesha Kaduskar and Sheeba Chaddha are the only ones who don’t have their shears out for Uday, who, as portrayed by Ayushmann Khurrana, seems always to be on the verge of debagging himself.

Maybe it’s just me, but I did not even understand the deal with ‘reforming’ a dude like Uday.

For all his perceived douchebaggery, I thought him just a normal guy trying to get by in the world.

When you first meet him he is resourceful yet tactless, has a pungent sort of wit, is a man on the make, is someone who gets hurt, and is thoughtful to the extent that any ‘real’ human being can ever be.

And when by the end of the movie this Dickensian runt is turned into a celestial softie, I got the feeling that what we have gained cannot quite take the place of what we have lost.

But while you can protest and picket about this presently popular form of character castration, what ultimately makes Doctor G a lazy, dishonest, work is the fact of it wanting it both ways.

The film is outwardly all for women, but evidently has no interest in them.

Every scene here has Ayushmann’s Uday as its central focus, so much so that no female character even takes a bathroom break or crosses a hallway without stopping to think about Uday or contemplate one of his many supposed peccadilloes.

And what do these women do when the hairy otter is not around? They call him up and lecture him.

At one point, I casually wondered how the women must have passed their time in a pre-Uday age.

Were they burning candles in front of his concept-picture, like some pagans tend to while waiting for their oncoming Messiah?

To each of the women in Doctor G, I wanted to personally scream out, ‘Get a life!’ and to the screenwriters of the movie, ‘Will you please give them some life?’

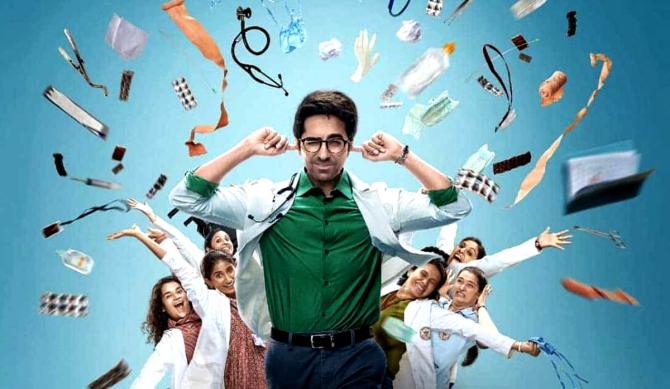

Doctor G may be filled with screenwriting blunders, in addition to being the product of a blinkered worldview; yet, detractors of Anubhuti Kashyap’s film are not wrong in foregrounding an obvious pickle: The Ayushmann Khurrana formula is getting stale.

Something that had started out as a movement against ‘problematic’ movies has today turned into a reservoir of ‘programmatic’ movies.

A fair deduction, but I think there’s more to the pickle.

What Khurrana made possible was an estimable approach — of stripping the mainstream Hindi film hero of his infallibility and his empty heroism.

But here’s what we often forget: In films like Bareilly Ki Barfi (a much under-rated performance), Badhaai Ho, Andhadhun and Article 15, Khurrana’s crutches were largely ‘artistic’.

His *real* achievement in the aforementioned films was that he generously contributed to making the Hindi film hero just one of the many interesting elements driving the narrative (A lot of the critical casting decisions in Bareilly Ki Barfi and Badhaai Ho began as his suggestions).

And then it befell him, the curse of the enfant terrible who gets too successful too soon: He became the biggest draw in his films.

This explains why, in a film like Doctor G, there’s no horizon beyond what his Uday can see, and no pastures other than what he breathes into existence.

Yes, what bothers me about the Ayushhman Khurrana formula is that the Ayushhman Khurrana hero, while continuing to play the errant person card, has begun to suck the oxygen out of the other characters.

Maybe Khurrana would do well to realize that his project was never merely about shrouding the Hindi film hero in a dark cloak. It was also about extending the spotlight.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article