Badhaai Do carries its audience on the wave of those little farces that come with being queer in India, a land where masculinity still has some say, observes Sreehari Nair.

By the end of Badhaai Do, things work out pretty well for the gay couple shown to be engaged in a lavender marriage.

Familial ordeals are smoothed out, detractors become championers, and everybody is brought in touch with their inner feelings. Even the wonderful Sheeba Chaddha, who plays a Garfield of a woman — yawning away gloriously, she’s always a little too dazed to be truly in the moment — is not denied the fruits of transformation.

Critics have been busy tracing a connection between the success of Badhaai Do and the film’s final 15 minutes.

It is being suggested that taken together, the upbeat mood and the big numbers illustrate a society on the verge of a radical new era.

It is also being suggested the film will inspire parents to suddenly grow a patient ear, a tender heart, and a whole new perspective on how to attend to the needs of their gay children.

Maybe all that will happen; who knows?

My beef, however, with the cheery ending is that it makes you forget that for about seven-eighths of its running time Badhaai Do doesn’t go down the easy route.

It doesn’t offer same-sex relationships a safe haven under that sweet-sounding but ultimately hollow advertising maxim of ‘Love is Love’.

On the contrary, the film silently argues that certain subtle differences do exist in the homosexual way of life, takes chances with laying out these differences well within the format of mainstream Hindi cinema, and creates out of these differences little comic routines while diligently avoiding nastiness.

What are these subtle differences, you may ask?

Well, why not begin by rounding up all those aspects that now and then make sex an exciting adventure for heterosexuals?

Yes, I am talking about the trading of dominance.

I am talking about willed submissiveness.

I am talking about the interplay of feelings covertly expressed.

Now mull over the following: wouldn’t a homosexual be experiencing all the above aspects of sex more regularly, and in considerably larger doses?

Two song sequences in Badhaai Do risk answering this delicate question.

The first one has to be among the most erotic sequences ever filmed in Indian Cinema.

Shot inside the blood collection room of a pathology lab, it plays out over a husky rendition of Hum Thay Seedhe Saadhe by Shashaa Tirupati, and features Chum Darang and Bhumi Pednekar.

In it, Darang tests her lover out, teases her with an image of sexual perfection straight out of childhood (the smiling nurse holding a syringe in her hand), feels her lover’s quivering nerves even as Tirupati’s voice gives to the disinfected room the atmosphere of a psychedelic underworld, and finally tightens the tourniquet around Pednekar’s arm in a moment that screams out like the onset of a long-awaited orgasm.

The other song-sequence in the film, Atak Gaya, is presently being shared on social media with such solemn gusto (what with the generous splattering of heart emojis) that it makes me groan every time it appears on my timeline.

If, however, you wish to genuinely appreciate the video of that song, watch out for the quick story being told there, and how it mixes kink with legitimate affection.

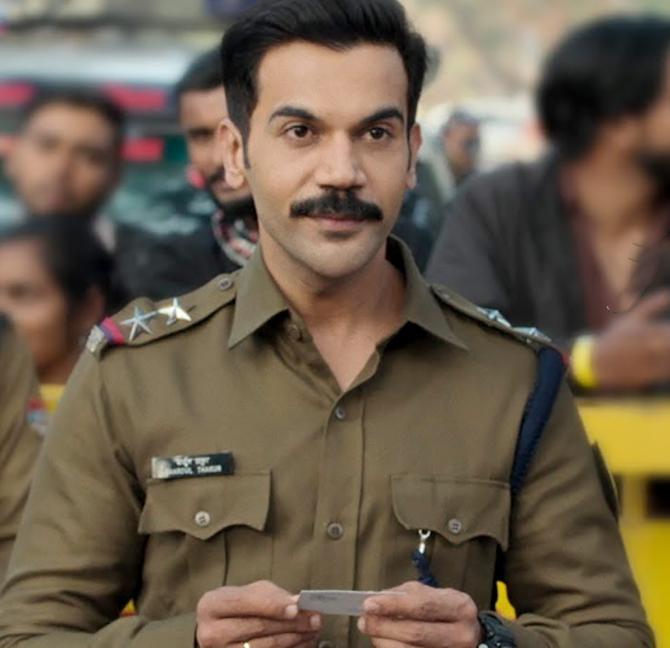

The story goes like this: Rajkummar Rao plays a cop, who takes special pride in penalising offenders, in escorting handcuffed criminals to their designated dungeons, and who carries out his little romance with a lawyer (played by Gulshan Devaiah), all the while propelled forward by the knowledge that the two men of law are, unknown to the world at large, breaking a rule or two on the side.

I understand that in a country of social justice warriors, it is fashionable to talk about homosexuality in the same tone that is reserved for candlelight vigils, violin music, and the wet tales that one sees put up on Facebook pages.

It is only natural that we bring up the restrictions, the lack of freedom, and the ever-suspicious eye cast on queer love — all of which are more or less true.

But it ought to be equally true that the destabilising elements in a homosexual’s life must form the flints and sparks of many a memorable sexual experience. And at its very best, Badhaai Do manages to get at these elements.

The film acknowledges that love is love, sure, have your liberal cake, but more importantly perhaps it acknowledges that in the stigma is buried the essence of the sting.

This talent for shading scenes with more than one psychic current is not widespread among film-makers, but it shouldn’t surprise fans of his first film (and I am one of them) that Harshavardhan Kulkarni is the man behind the density.

Hunterrr was about Mandar Ponkshe’s sexual conquests and failures, but running through the protagonist’s many ruses and escapades were the domestic jingles being composed by his parents who, after a lifetime of experiencing what Ponkshe was after, had nothing more to exchange than petty wrangling.

But there’s another reason why Kulkarni is the ideal man to tackle a subject like the one in Badhaai Do: and that’s got to do with his knack for bringing to conventional narratives unexpected and often shocking undertones.

In Hunterrr, without so much as a piece of dialogue, a straight line was drawn from sex to death, from sex to one’s awareness of one’s mortality.

Now, in Badhaai Do, the lines go from sex to vital fluids — to blood, to spit, to feces, and somehow they all connect.

For, when you come down to the basics, doesn’t sex occupy the same bodily dimension as those other elemental discharges?

And who among us wouldn’t have at least one example to cite from memory, when a night of sleeplessness had followed a night of thunderous lovemaking, when a stretch of post-coital silence had competed for supremacy with a lover’s persistent snoring?

One of the writers of Badhaai Do is Akshat Ghildial (one half of the duo responsible for the script of Badhaai Ho), and you can see why Ghildial must have trusted Harshavardhan Kulkarni with pulling off his vision.

Like Kulkarni, Ghildial too has an eye for those ultra-fine filaments that bridge two worlds moving at entirely different speeds.

And for the most part, he doesn’t use his perceptions for the purpose of grandstanding, but to throw light on a set of interesting paradoxes.

While discussions relating to Badhaai Do may be centered on the subject of ‘social progress’ and other allied issues of grave concern, a careful dissection will tell you that the film has struck a chord with the mass audience because it attempts to not elevate them, but simply to diddle around with their precepts. For instance, the film repeatedly takes that well-set mainstream formula of the comedy that comes with role-playing, and cleverly transposes it onto the sexual plane.

Sample a scene of the police officers gracelessly running around a public park detaining lovers.

A heterosexual couple is detained and brought to the gay cop played by Rajkummar Rao, who proceeds to gleefully debase and punish the two.

Next, a lady policy officer scans a petting grove and calls out to her colleague.

‘Sir, Laasbians,’ she announces.

The colleague, a male officer, looks forward with much anticipation to two women being pulled out from behind the bushes. But he’s hit with a category mistake, and two men emerge instead of two women, leaving the colleague with no option but to reveal his disappointment.

When the gay couple is brought to the gay cop, who’s busy punishing the heterosexuals, he shoos his ‘brothers’ away, almost on moral impulse you see, and then offers a swift explanation: ‘These idiots are out to spoil the reputation of our great republic.’

The aforementioned scene works on multiple levels.

Sexual embarrassment that takes the form of sadism, indifference toward ‘the other’, the tendency to take refuge under patriotism when everything else fails, each of these is briefly visited.

But one of the reasons why the scene is so readily enjoyable is because it is, all things considered, about the everyday comedy that comes with trying to keep up appearances. And while this is a country that perseveres with lionising S S Rajamouli’s hyper-masculine films (though the weariness in the effort has started to show), it’s also true that for an Indian audience of 2022 imaginatively handled, there’s bound to be no bigger square than a failing patriarch who continues to tug at his last threads of glory.

The multi-level comedy of masculinity is ramped up in another scene, one in which the gay cop’s senior together with his wife visit the lavender couple in their police quarters.

Here, we see Rao’s cop resorting to casual sexism in order to prove the authenticity of his marriage (how wicked!), and both Ghildial’s writing and Kulkarni’s direction doesn’t merely soar at this point, they start to fly in all possible directions.

The scene builds and builds till it becomes a superb commentary on each of the four mates’ separate struggle to gain the upper hand, and while this happens, a police walkie-talkie goes on broadcasting beat updates from around the city.

Amid a scene that gets progressively more and more complex, we hear the walkie-talkie going, ‘Cheetah One, swing your baton; that’ll scare the dogs away’ — and you watch in awe as the neon-barred truths of the street and the stifling wisdom-flames of the hearth move in and out of each other’s shadow.

If the two films he has written are any indication, we can safely proclaim Akshat Ghildial to be one of the few screenwriters around who believes in the essence of noble India, and believes that it is best captured not when a conservative is scorned at but when a conservative’s attempts at finding relevance in a fast-changing world is documented.

The gay cop’s traditional family accepts his demand for a Muslim bride, but by the time the acceptance arrives the would-be groom has already brought up the next station of liberal thought.

Ghildial seems to understand something that few progressive-minded writers understand: when you get down to it, nobody wants to be a conservative.

It’s just that everybody craves order (even the progressives prefer it to chaos), and he, Ghildial, has an antenna extended for the humour that transpires when this search for order is disrupted.

Badhaai Do, much like Badhaai Ho, doesn’t aspire to be a breakthrough film. But for a while it manages to be an inventive mainstream film because it doesn’t strive to create separate districts for ‘progressives’ and ‘conservatives’, and thereby deepen that concept made most chic by the liberals: PolariSation.

The inventiveness of the film can be discerned in its scenes of intimacy, where the desires of the body are shown to not bow down before the tenets of good taste.

But if the film has performed so well, it’s not because it confronts an Indian parent with the question: How would you react if you find out your child is gay? That is too much tartness to take in two hours.

Badhaai Do carries its audience on the wave of those little farces that come with being queer in India, a land where masculinity still has some say.

The approach ensures that even somebody who is not that sensitive to the issue of gay rights can enjoy the comedy without condescending to homosexuals.

It also helps that the film doesn’t make angels out of its homosexual protagonists.

They are portrayed as people with human shortcomings, who happen to be on the margins of accepted culture; and Rao’s cop, especially, is both an outlier and a victim of social conditioning.

Now that I see it, there’s perhaps a larger lesson on secularism and vibrant democracy hidden within the entrails of the film.

We are often told that an open society is one where nobody steps on anybody’s toes. But isn’t that the defining etiquette in fascistic societies that promote dull thinking?

A society worth longing for is not one in which we would all forget our differences and hug and weep in each other’s arms, but one in which we can poke fun at our differences while trying our best to not be spiteful.

By the same token, secularism in our democracy, I don’t think can ever be achieved by Hindus and Muslims being totally respectful to each other. It can be achieved only when there’s space for healthy banter about multi-limbed Gods, and space to every now and then crack a circumcision joke.

Source: Read Full Article