Aseem Chhabra lists the movies that taught him about the Idea of India.

As an entertainment journalist and movie buff, I watch a lot of films.

And despite the many degrees I have earned, I am convinced that my most meaningful education has come from cinema.

I have learned so many things from watching films (and sometimes from reading books as well) — the idea of love, loss, heartbreak, and about the good and the bad that co-exist in our world.

Jhumpa Lahiri writes in her novel The Namesake: ‘That’s the thing about books. They let you travel without moving your feet.’

I believe the same is true about films.

I know I have learned a lot about the world I live in from the films I have seen.

And more than books about the politics and history of India, there are several films that have made me understand and appreciate the country of my birth with all of its complexities.

On the occasion of India’s 71st Independence Day, I made a list of 10 Hindi films — in alphabetic order — that have taught me about the Idea of India, made me comprehend the vast layers of this diverse and sometimes divided countries.

And I am still learning as I watch more films.

Mulk, for instance, is a terrific example of why a person of one faith should not challenge someone from a minority religion to prove his or her loyalty to India.

As the film says, India belongs to every individual who was born in this country.

Ankur (1974)

I was a teenager in school when I saw Ankur at Delhi’s Regal Theatre.

I was drawn more to the film because a classmate told me that his cousin’s (Shekhar Kapur) then girlfriend (Shabana Azmi, in her first role) was brilliant in the film.

It was also Shyam Benegal’s first film, so I did not know what to expect.

Benegal’s story is set in the mid-1940s, before Independence, in a small village close to Hyderabad.

The caste and class divides are glaring and accepted here, and so, a rich landlord’s son (Anant Nag) sleeps with a farm labourer’s wife (Azmi), but hardly anyone raises any objection.

But the violence at the end of the film, the cruelty with which the landlord’s son beats up the farm labourer is a stark reminder that this could happen in India in 1974 or even in 2018, as we often read in the headlines these days.

Azmi’s outburst at the injustice towards her husband, and the last scene when a little boy throws a stone at the landlord’s window, are among the most effective and angry protest moments I have ever witnessed in a film.

Band Baaja Baaraat (2010)

Maneesh Sharma’s 2010 film is an odd choice to follow Ankur.

But Band Baaja Baaraat is one of the true representations of post-liberalisation India, where people living in the outskirts of a major city have developed this ‘anything is possible’ frame of mind.

A romantic comedy and the best of Bollywood, BBB is the story of Bittu Sharma (Ranveer Singh) and Shruti Kakkar (Anushka Sharma), who live in Janakpuri, once considered the fringe part of Delhi but now is an exploding middle class colony.

Shruti develops her idea to start a wedding planning business, to counter a more successful businesswoman’s arrogant and classist attitudes.

Bittou (an energetic and earnest Ranveer in his first film role) joins her as a ‘binness’ partner.

There will be love, a very hot kiss and a sex scene that will affect the partner’s business plans.

But for a Hindi film, there is bound to be a happy ending.

What impresses me about BBB is its keen observation of India on the move, and the film’s two attractive 20-somethings with an attitude that nothing can stop them.

Garm Hawa (1974)

One of the best Indian films of all time, Director M S Sathyu’s Garm Hawa is based on Ismat Chughtai’s story, and Kaifi Azmi and Shama Zaidi’s script.

The film is a powerful human document, a tale of an Agra-based Muslim family’s plight immediately after Independence.

Pressures mount on Salim Mirza (a heart-wrenching performance by Balraj Sahni) as his business fails, and his brother and elder son’s families decide to move to Pakistan.

But despite a devastating tragedy, Salim, his wife (Shaukat Azmi) and their young son Sikandar (Farooq Shaikh, in his first role) choose to stay back in India.

Garm Hawa is testament to the fact that the Muslims, who stayed back in India after Partition, are as much Indians as the majority Hindus and those belonging to other minority religions.

It is also one of the warmest, most beautifully acted films, with charming humour and a lot of playfulness. It features one of the best qawwalis, Maula Salim Chisti, sung by Aziz Ahmed Khan Warsi.

Manthan (1976)

Shyam Benegal’s Ankur looked at the caste issues in a village outside Hyderabad.

But the director’s fourth feature, Manthan, takes on a full-on examination of caste politics in rural Gujarat, where some city folks with good intentions want to start a milk cooperative.

With a cast of what had become his repertory actors (Smita Patil, Naseeruddin Shah, Girish Karnad, Amrish Puri, Anant Nag and Mohan Agashe, among others), and a tight script by Vijay Tendulakar (with dialogues by Kaifi Azmi), Benegal weaves a complex narrative web.

Manthan‘s drama is entertaining, but it is such a great textbook case of how things can go wrong in a setting where caste becomes the primary way for people to define themselves.

A sense of disappointment sets in, as the film is about to end, and good intentions fall flat in the face of caste identities.

But Manthan’s end also promises a sense of hope.

Monsoon Wedding (2001)

Mira’s Nair’s Venice Film Festival Golden Lion winner Monsoon Wedding is one of the most exuberant celebrations of all things Indian, especially our weddings and how they are marked with parties, dance, music, songs, food and alcohol.

Some may feel that the film projects the country’s elite and their ostentatious celebrations.

But this Punjabi wedding dramedy is layered with affairs, romance, flirtations, a dark family secret, and lovely upstairs-downstairs tales of class divide.

Monsoon Wedding is so much fun. It features a lot of humour, one of the best soundtracks ever, including Sukhwinder Singh’s Aj Mera Jee Karda — a song that makes you want to dance each time you hear it — remixes of classic Hindi film songs and the realisation about how much Bollywood has become part of our lives.

Monsoon Wedding is also a reflection of the new India.

It is a must watch film for those who want to understand the heartbeat of today’s India, at least in the north and in the cities.

Mughal-e-Azam (1960)

K Asif’s three-plus-hour long magnum opus is part history, part fiction, and full-on entertainment, along with a strong sense of a secular India as envisioned during the time of Akbar.

Today’s political climate challenges a lot of ideas of the Mughals and many even consider them as invaders who occupied India.

But Akbar, his son Jahangir and their successors were born in India and so they were definitely Indians.

K Asif’s grand melodrama amply clarifies that the Mughals made India their home. That part of Mughal-e-Azam‘s history is accurate.

But politics apart, Mughal-e-Azam should be appreciated for its powerful dialogues (the writers included Kamal Amrohi, who later directed Pakeezah and Zeenat Aman’s father Amanullah Khan), terrific performances by Prithviraj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar and the very sensual Madhubala, spectacular sets, dances, songs, and unforgettable compositions by Naushad.

Muhafiz (In Custody) (1993)

More than three decades after he became a film producer, Ismail Merchant adapted Anita Desai’s novel In Custody, shortlisted for the Booker Prize and directed an Urdu language film called Muhafiz.

The film (and the novel) narrates the story of a hapless college professor (Om Puri), who takes up an assignment to interview an aging Urdu poet (an overweight Shashi Kapoor, in one of his best performances) whose final years are being wasted between two bickering wives (wonderful Sushma Seth and Shabana Azmi) and a handful of hangers-on, who pretend to value his poetry but are mostly there for free alcohol and food.

Hardly anyone — other than the college professor — care for poetry and the state of the Urdu language.

A comedy with touches of tragedy, Muhafiz is a sad portrayal of life in Independent India where real art, culture, good writing and poetry are largely underappreciated.

For those who care for good cinema, there is much to appreciate in Merchant’s film, including the crackling script by Desai and Shahrukh Husain, the performances, the music and Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s poetry.

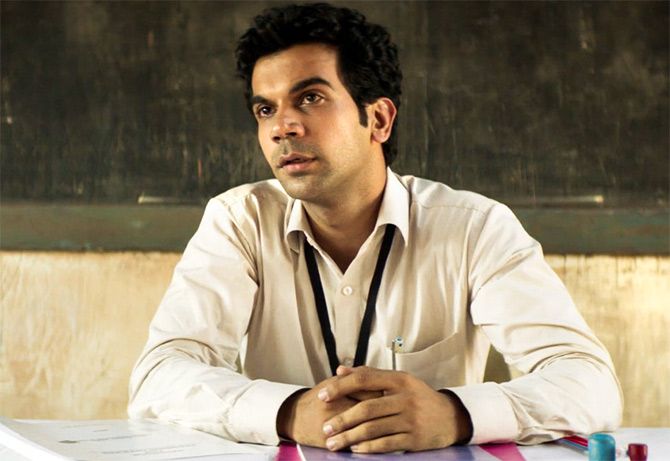

Newton (2016)

Director Amit Masurkar’s award-winning film Newton celebrates India’s Constitution that ensures the country’s adult citizens’ right to vote and exercise their choice in selecting their leaders, members of legislative assemblies and Parliament.

The film is narrated from the perspective of the protagonist Newton (a terrific Rajkummar Rao), an overeager, sincere, very adamant and brutally honest election officer whose task is to conduct elections in a remote part of India, riddled with Maoist activists and tribals whose daily struggle for survival will not be impacted by the vote they cast.

Often funny, Newton sets out to be a tribute to India’s democracy.

It is also a very thought-provoking film exploring the full extent of the democracy that means more to some Indians than others.

Pyaasa (1957)

Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa is a deeply romantic film, packed with heartbreaking punches.

It is a story of a poet shunned by his first girlfriend, who marries for money and love, which he later finds from a prostitute, who appreciates his writings.

There’s a lot going for the film from the star cast — Dutt himself, along with Mala Sinha and Waheeda Rahman — and the songs composed by S D Burman and written by Sahir Ludhianvi.

Abrar Alvi’s narrative has kept the film in the collective conscience of generations of Indians who love old classics.

Pyaasa was released 10 years after India attained Independence and it eventually questions the state of a bright future promised to the nation by its idealist first prime minister.

In one of the most popular songs Jinhe Naaz Hai Hind Par, the film offers a reality check on where the nation is at that particular juncture.

In Guru Dutt’s vision, the nation has failed its people, especially the downtrodden, the disenfranchised and those who live on the fringe of society.

Shree 420 (1955)

If Pyaasa presented a bleak state of affairs in the newly Independent India, Raj Kapoor’s Shree 420 (as with many of his other films) offers a sense of hope, despite villainous rich characters, unscrupulous money lenders and a hot dancer who attempts to lure Ranbir Raj (Kapoor, at times reflecting a Charlie Chaplin-inspired persona) into the bad world of corruption and moral rot.

Raj Kapoor’s regular scriptwriter K A Abbas, a journalist with a socialist bent of mind, always wrote simplistic film narratives.

So, in Shree 420, good wins over evil (including the film’s pure and innocent female lead, Vidya, played by Nargis, who wins over the love of Raj from the vamp Maya, played by Nadira) and the rich and powerful have to bow down before the poor.

And if it is a Raj Kapoor film, the message of a bright future for India and Indians has to be liberally sprinkled with several songs, each one a big hit, including the somewhat clichéd anthem for every Indian living outside the country, Mera Jota Hai Japani.

Source: Read Full Article