There’s a peevish quality to all the films on this list, which is fitting, because peevishness is the defining characteristic of most Malayalis.

These films, even at their saddest, darkest and grossest, retain their sense of humour, their sense of proportion, which again is something you associate with a Malayali.

Finally, as in the case of Malayalis, who are known to carry on in the toughest of conditions, these films have survived bad picture quality, poor subtitling, general neglect, and still remained relevant and vital.

Sreehari Nair lists 10 classic Malayalam movies you can watch on OTT.

Manichitrathazhu

Where to watch? Disney+Hotstar

One of the many things that separates Manichitrathazhu from its substandard remakes is the original film’s wet look, somehow the look of untrammeled mystery, of fermenting evil.

For my money, this is our finest potboiler. And like all great potboilers, here too, the gaps in logic are plugged by a searing desire to never let the viewer off the hook or let a routine go on for too long.

Shobana’s gaze of regretful longing is balanced by Mohanlal’s buoyancy, but his velvety touches soar just as much.

When the jaunty psychiatrist, Dr Sunny, takes a break from his deviltries and pranks to eke out his swift appreciation for a Kathakali performance, with an off-the-cuff shake of his head, he recalibrates the priorities of the movie.

An index of Manichitrathazhu‘s enduring popularity among Malayalis is how little its dedicated audience cares about Dr Sunny’s psychiatric mumbo jumbo.

I have had more than a few close relatives who have happily gone to their graves believing this to be ‘a damn good ghost story’.

Ponmuttayidunna Tharavu

Where to watch? YouTube

A Vanity Fair of performers least vainglorious. Raghunath Paleri’s continually unfolding, witty script about pastoral pettiness, blind beliefs and artful dodges inspired Sathyan Anthikad to go all out with his stock company of actors.

So Oduvil Unnikrishnan comes on with a fluttering moustache, Karamana comes on with an exaggerated Malabar headgear and Jagathy Sreekumar (not an Anthikad regular by any measure) is an oracle with an overflowing mane.

The characters, though caricatures, are immensely memorable — from Krishnankutty Nair whose bed-ridden twig of a body becomes a source of constant anxiety for his family of ever-ready mourners to Sankaradi as an insufferable moralist who turns into an old-world prurient by night.

Other ‘incomparables’ like Philomina, Mamukkoya, KPAC Lalitha and Innocent make up the enclosing circle, at the centre of which is Sreenivasan as a tender-hearted goldsmith and Urvashi as the blithe girl who breaks the goldsmith’s heart.

The entire cast seems to be performing in clover, and Sreenivasan’s foolishly-in-love face sets off Innocent’s genius at playing the sweet-talking swine.

The movie was first released as The Goldsmith Who Laid The Golden Eggs and after unrelenting protests from the goldsmith community it was renamed The Goose That Laid The Golden Eggs.

Back in 1988, full-page ads announcing the changed name had appeared in the newspapers, accompanied by a note from Sathyan Anthikad that read, ‘Here’s hoping the geese don’t take offence to our new title.’

Irakal

Where to watch? Amazon Prime Video

Thilakan is magisterial as Mathukutty, a hard-nosed rubber baron, the grand yet loveless façade of whose mansion shelters a well-oiled culture of cruelty.

Mathukutty’s youngest, Baby (Ganesh Kumar, in his screen debut), may strike you as a straight sadist at first but the scope of this K G George masterwork expands as we keep at it.

In one scene, we hear Baby expressing his reservations about conventional sex thus: ‘I do not like it when somebody readily gives me something; my real joy is in snatching it out of their hands.’

Later, we see this self-appointed executioner shedding a few tears after he has successfully completed one of his many strangulations.

It then dawns on us that murder is an escape for Baby; that he too is one of the ‘victims’ that the title is trying to point us towards.

Such sequences should put to rest all those crude political readings that have attended the movie since its first show.

K G George’s temperament is both humanistic and gothic; and he views the human race as capable of doing so much better, if only we weren’t so doomed and damned.

George’s ambivalent stance toward religion is reflected best in the character of Mathukutty’s old man, who spends his time cooped up in his chamber, creating stews out of dramatic Bible verses and his son’s brutal exploits.

There are a lot of strange camera angles to contend with; though the sudden close-ups, used to heighten the force of psychopathology, may look dated now, at its heart this is a rich, contemplative picture that moves along on a current of slowly enveloping despair.

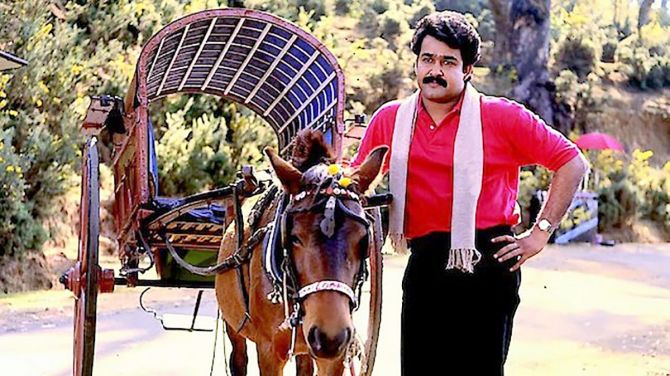

Kilukkam

Where to watch? Disney+Hotstar

Watching it again recently, it struck me just how important ‘mist’ is to the magic of Kilukkam. In this Ooty-set movie, the characters, one by one, emerge from the mist and mark their territory.

Other times they go in and out of the frame at will, as in the case of that superbly performed scene of Innocent abusing Thilakan while doing a freestyle trot across the screen.

Thilakan and Jagathy are the two pilings holding up the film’s structure, and the other actors — including Revathi, displaying a peculiarly boyish charm, and a surprisingly long-chinned Mohanlal (who knew the great man had such a prominent mandible?) — sportingly move this way and that when pushed.

The whole movie has been made in that improvisatory spirit so evident in Priyadarshan’s strongest works.

Yet, for the last 32 years, it has informed the way people from Kerala banter with each other.

This movie alone is responsible for a good two dozen catchphrases that an average Malayali carries around in his head at all times.

Elippathayam

Where to watch? YouTube

Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s scorching dissection of empty feudal pride is also a comedy of inertia and stasis. The setting is decadent but Adoor’s gentle wit pervades the proceedings.

Karamana Janaradanan, as Unni, wishes to conduct his entire life from his armchair. And when he rebukes his sisters for something ‘not done right’, you can see how much he has softened himself over the years.

Adoor also allows Unni’s unfulfilled desires to break through every now and then.

In one scene, the naturally petulant feudal lord gets ready to whack a little boy, who has been stealing from his backyard.

The boy’s mother, one of Unni’s house-workers, intervenes by flashing her cleavage and thereby securing the safe escape of her kid.

It’s a hilarious scene, and it ends with Unni silently counting up the chance pleasures that life has occasionally thrown his way.

Amaram

Where to watch? YouTube

Mammootty’s Achootty is as elemental as the salt of the sea he swears by.

The actor’s perfectly modulated performance is what elevates this Bharathan-Lohitadas melodrama, set in a fishermen’s hamlet in Alappuzha, to the level of unforgettable drama.

The characters seem to be yelling at each other in their bid to outdo the susurrations of the waves.

Bharathan allows the music in this bellyaching style of talking to emerge, and then he gives us an actual conflict, a war of egos, which ends with the mercurial Achootty bringing back the son-in-law he disapproves of (Ashokan is all eyeballs and arched eyebrows) from the bosom of the sea.

Pretty broad stuff but full of feeling; and it’s heavenly to see Mammootty’s lips curling and to hear his voice breaking right in the middle of a long dialogue.

He is a happy imitator of Nature here.

Godfather

Where to watch? Disney+Hotstar

I am perhaps the only Malayali who has a rather low opinion of Siddique-Lal’s feted buddy-buttslap comedy In Harihar Nagar (I find the skirt-chasers in that movie more intent on making each other jealous than actually getting girls).

But I have no such problems with the directing duo’s 1991 release, Godfather.

Theatre veteran N N Pillai (then, mourning the death of his wife) is cast as Anjooran, a widower who has pledged himself and his shaggy, ready-to-rumble sons to a life of complete celibacy.

Anjooran sits on his porch perfecting his nasal twang, even as his gate bears the sign, ‘Women Not Allowed’.

The old crank’s wrongheadedness is the stuff of colourful dictators.

It’s a sparkling premise, made frothier by the complications that arise when one of the four sons loses his willpower and falls for a girl — and she is a Capulet to his Montague, no less.

The gags-for-the-sake-of-gags approach produces some remarkable instances of visual and verbal slapstick: sketch jokes and marionette tricks.

There’s also a fair amount of sentimentality, but watching those hairy blimps cry and beat their chests is amusing in its own right.

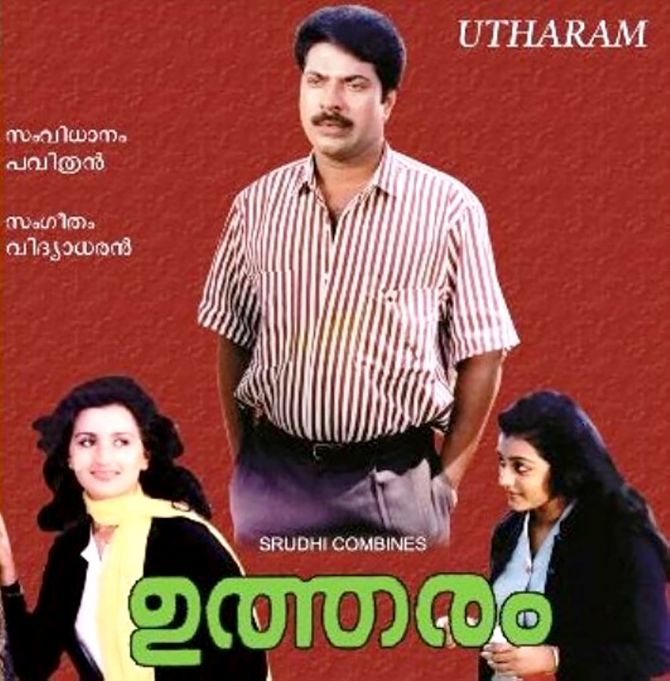

Utharam

Where to watch? YouTube

One of the most deeply felt investigative thrillers made in this country, and it has one of the most sensual opening scenes you’ll ever see: Trees crowding for sky-space, kennel and rubber sheets, a grumbling old man, a gunshot, a dame lying dead in a pool of blood, a shriek.

Mammootty is Balachandran, a journalist who retreads the life of Selina, the poetess who kills herself.

As the persnickety Balu works out the cause of the suicide, he unearths a dreamy, dopey, painful past in which girlish cheerfulness, evil, and poetry had commingled.

Neither M T Vasudevan Nair’s script nor Pavithran’s directorial approach feels exploitative, and we can sense the mind of the persistent poetess ringing through the narrative.

Mammootty’s voiceover in the climax, explaining Selina’s rush to self-slaughter, is like an unblinking eye cast over a moment of mortal desperation.

Oridathu

Where to watch? Disney+Hotstar

The village in Oridathu does not resemble a ‘movie village’ in the slightest. There’s an atmosphere of living interrelationships, connections established obliquely, and Aravindan, the director, seems to be using as inspiration the village of his childhood and adolescence: The story is set in the latter half of the 1950s, in a North Kerala dustbowl of full-bodied women, bare-chested men, kids in suspenders, and weeklies, one of which carries an article on Pather Panchali.

Aravindan’s special gift (as manifest in his cartoons) was for illuminating the responses of people who come up against something larger than themselves, and his penultimate motion picture concerns the electrification of the dustbowl.

At first, the villagers in Oridathu are transfixed by electricity and the paraphernalia that comes with it. But when it becomes the seat of misunderstandings, disruptions and a few deaths, the villagers begin to wonder if life was better without this touch of modernity.

Sure, there are ironies and paradoxes, but there’s no sweetening of the material. The downtrodden in this movie seem to believe that being exploited is their destiny, and their creator is too proud an artist to change their line-of-thought.

Though the movie plays out with unhurried care, there’s always something to take in, to marvel at. Aravindan and his cinematographer, Shaji N Karun, photograph everyday incidents as if they were events of historical dimensions.

We get this feeling of an entirely new civilization being built right before our eyes: watching the village being electrified is like getting to witness firsthand the designing of Harappa’s drainage system or the construction of the amphitheater in Rome.

Season

Where to watch? YouTube

I suppose Padmarajan’s mission statement going into this movie was to make Poojappura Central Jail breathe as freely as Kovalam Beach.

Mohanlal is Jeevan, and his voiceovers bouncing off the jail walls have the same exuberance as Wordsworth floating on high over vales and hills.

We can safely assume that, to the Malayali ticket-buying public of 1989, those voiceovers must have seemed as discordant as Illayaraja’s visionary soundtrack: the movie was a resounding flop!

This is a revenge drama held together by Padmarajan’s well-documented love for certain pockets of Trivandrum as well as his dread about spending a night alone in the city.

The love and the dread combine to form the fatalistic Jeevan, a revenge-movie hero who is out to make a ‘phony’ of every revenge-movie hero who came before him.

Jeevan is a romantic committed to vengeance, a diarist who abhors dull stretches, and he signs off with wistful nods to the streetlights, to the dew, to the blood stains that cover every part of his body.

Source: Read Full Article