Joshi, who travelled to different parts of the world for hockey, had just one wish left from his bucket list: to watch India play at the Olympics. The Tokyo Games were on his wish list.

A Kenyan hockey team touring India is not an event that would enthuse many, not even the die-hards. However, when the African minnows travelled to New Delhi in the 90s, one man from Sehore on the outskirts of Bhopal bunked office and made the trip to the Capital.

It wasn’t just to watch Kenya play. He, instead, wanted to meet the team captain with a rather unusual request. A few years earlier, India had played a series in Kenya and he was desperate to find out the names of the two goalscorers missing in his list.

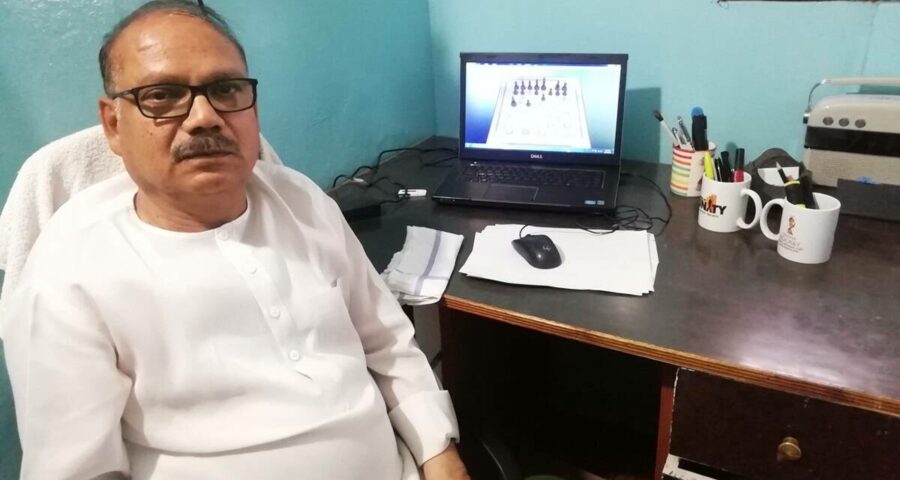

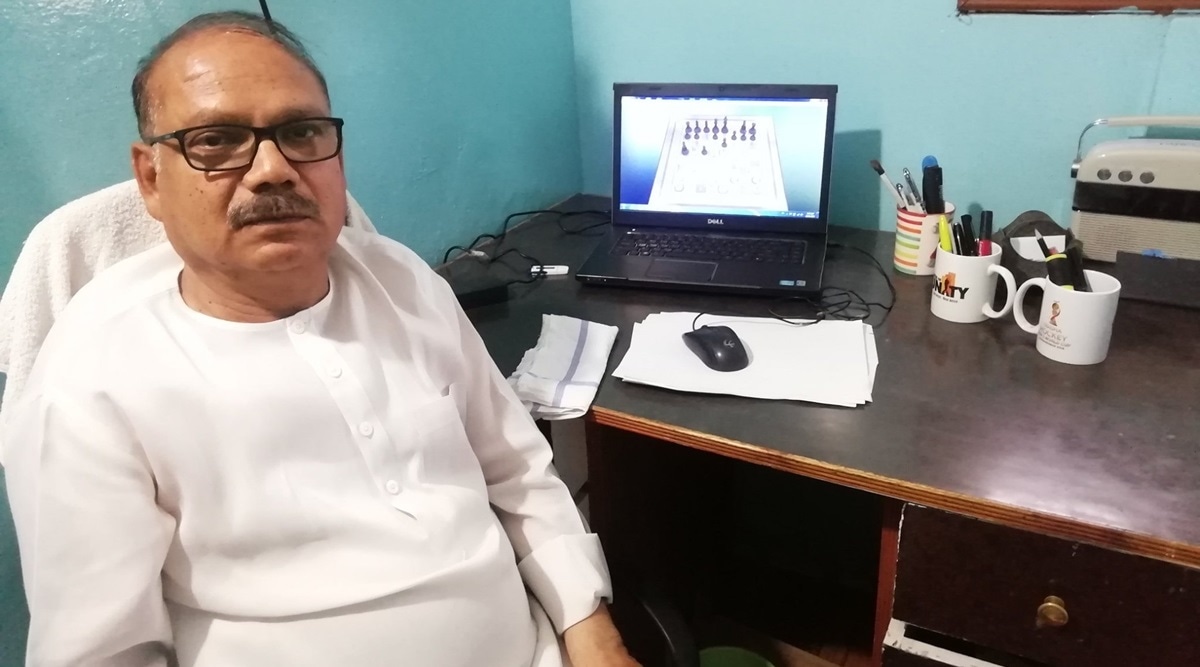

It was this dedication to his craft that made Baboolal Goverdhan Joshi, who passed away on Tuesday due to Covid-19, one of the most prominent hockey statisticians with an unparalleled body of work. He was 67.

At a time when professional sports had dedicated teams to maintain statistics, Joshi was a one-man army in a sport that was bereft of any such data, especially on Indian players. He went to extreme lengths to make sure not a single goal scored by an Indian went unrecorded. This, despite the sport not being widely telecast, matches being played at irregular intervals and barely any information available on the web, making stats-keeping that much harder. Yet, for close to five decades, he has been a go-to man for federations, players and journalists for all the numbers related to hockey, more so the Indian game.

A retired engineer with the Madhya Pradesh Water Resource Department, Joshi’s tryst with numbers began with the 1970 Asian Games in Bangkok, when he started keeping notes for himself listening to radio commentary of India’s matches. As India won three back-to-back World Cup medals, starting with the bronze in 1971 and culminating with a gold medal in 1975, Joshi’s interest in the sport grew further.

It was during this period that he started keeping stats seriously – first by making a £10 subscription to the World Hockey Magazine, which the International Hockey Federation (FIH) published monthly with all match data (“The subscription cost was more than my monthly salary, but still I somehow managed,” Joshi often recalled).

He even paid advance money to a newspaper vendor in Bhopal for copies of The Hindu, which he referred to for hockey match reports. Once a month, Joshi travelled to the state capital to collect his bundle as the daily wasn’t delivered to Sehore. After a decent database was established, a regional newspaper started publishing his stats during the 1978 World in exchange for a token amount.

That encouraged him to travel for hockey by taking leave from work. He started by visiting national training camps, where he collected data of every Indian player first hand. When he visited Lahore for the 1990 World Cup, he collected data of players from the leading nations from the team brochures.

It’s a practice he continued till the very end through more or less the same means: meet players and officials in person and gather data as many hockey matches are not shown on TV even today and sketchy details available online.

The stockily-built man with hearty laughter was an unmissable presence at every major hockey tournament, especially the ones held in India.

“He did painstaking work to keep his records updated,” Joshi’s son Shravan said. “He used to dictate each stat and I fed it on the computer. And like a teacher, he used to rebuke me for any spelling mistake or wrong entry I made,” Shravan said.

His son wasn’t the only one to get an occasional firing. Joshi would even chide the FIH for their improper upkeep of stats and often urged Hockey India, the sport’s domestic governing body, to maintain the historical data related to the Indian players. Joshi would instantly correct the errors made in the official accounts by referring to the volumes of work he carried along.

Even in routine conversations, he would randomly throw stats and trivia, at times even reminding the visiting teams of the significance of their goals. “We have to figure out a way to not just preserve his legacy but also carry it forward. He invested his entire life for this, we can’t let it go waste,” Shravan said.

Joshi, who travelled to different parts of the world for hockey, had just one wish left from his bucket list: to watch India play at the Olympics. The Tokyo Games were on his wish list. As fate would have it, his last post on Facebook was about India at the Olympics. “Indian hockey team’s performances (against Olympic champions Argentina) in preparation for the Olympics, which are three months away,” he wrote, “bring a smile to my face.”

Joshi’s post number 1226 (of course, he numbered them!) summed up the man: a die-hard with unwavering faith in the team and always smiling.

Source: Read Full Article