Cheteshwar Pujara could measure his life and world in the eight years between the two Motera Tests and feel immensely proud and contended. From old to new — a lifetime of memories.

The last time Cheteshwar Pujara played a Test match at the Motera, in 2012, he was just 25, clean-shaven, with barely a stubble, let alone a more defined beard that he spots these days. He had come straight off his engagement in Rajkot, his home-town that’s a four-hour drive away from Ahmedabad, he hadn’t yet nailed the No 3 spot. He alongside Virat Kohli, was thrust with the uneasy burden of carrying the legacy of the fab four forward, of which only Sachin Tendulkar remained.

Eight years on, in 2021, four days away from his reacquaintance with Motera, he is 33, a doting father, a world-beating batsman with hundreds in Australia, England, and South Africa, the ninth highest run-getter for his country, and with little to prove to himself or the world (anyway, he never conceded the impression that he has anything to prove to himself or the world). He could measure his life and world in the eight years between the two Motera Tests and feel immensely proud and contended. If he closes his eyes and meditates, he could see those years flash like a blur in front of him. From Motera (old) to Motera (new)—a lifetime of memories.

There was a sudden gush of excitement in his voice when he looked back at the 2012 Test. The most obvious reason for that Test to be special, he says, that it came just after he got engaged. “That Test will always be a special one, because it was the first I played after I got engaged. It will always have a special place in my heart,” he says.

That he scored a double hundred (206 in 513 minutes with a barely a blemish or shot in anger), against an attack featuring James Anderson, Stuart Broad and Graeme Swann, would undoubtedly make the particular outing even more memorable. It was Pujara’s second hundred, but it was this knock that stamped the self-effacing genius of Pujara, that furnished assurance in the post-Rahul Dravid era.

In many sense, the knock was a precursor, a preview into his methods that would lead him to the pinnacle of the game. Those dancing feet when he repeatedly glided out to smother the devilish off-breaks of Graeme Swann. Those dextrous hands when he defended the reverse-swinging James Anderson, that sculpted discipline and drilled judgement when he left the out-swinging Stuart Broad, that cold-eyed ruthlessness when his eyes met a loose-ball, those reserved celebrations (just a smile, a nod in the direction of his teammates and then back to business, then as well as now) and that rare gift of patience. Even back then, he was a throwback and even now he remains one, unhinged by any temptation to change. A fixed world.

He also explained his batting philosophy: “I never like to get out. There’s always a price on my wicket. Even after scoring a double-hundred I never wanted to give away my wicket. That’s the reason why I’m able to score big runs.” Bowlers world over would offer painful testimonials.

A lot has changed in the intervening eight years, yet, a lot has remained still. Technically, he has made minor alterations to his game, like reducing the flourish of his cover-drives, one of his most productive shots during the double hundred, but the soul remains intact. The heart, grit and greed for the runs.

All these virtues, he believes, would see him through his longest stretch without a three-figure score, the last one coming as far back as January 2019, the drought spanning 26 innings. He’s not unduly worried, certainly it has not reached a point to feel alarmed. “I have started well, got off to starts but got out, unfortunately, a few times. The way I am batting, although the three-figures haven’t come, I am hoping it won’t be too far away. As a batsman, what is in my control—my practice, preparation, process—it’s been wonderful. I’m confident of getting a big score very soon,” he explains.

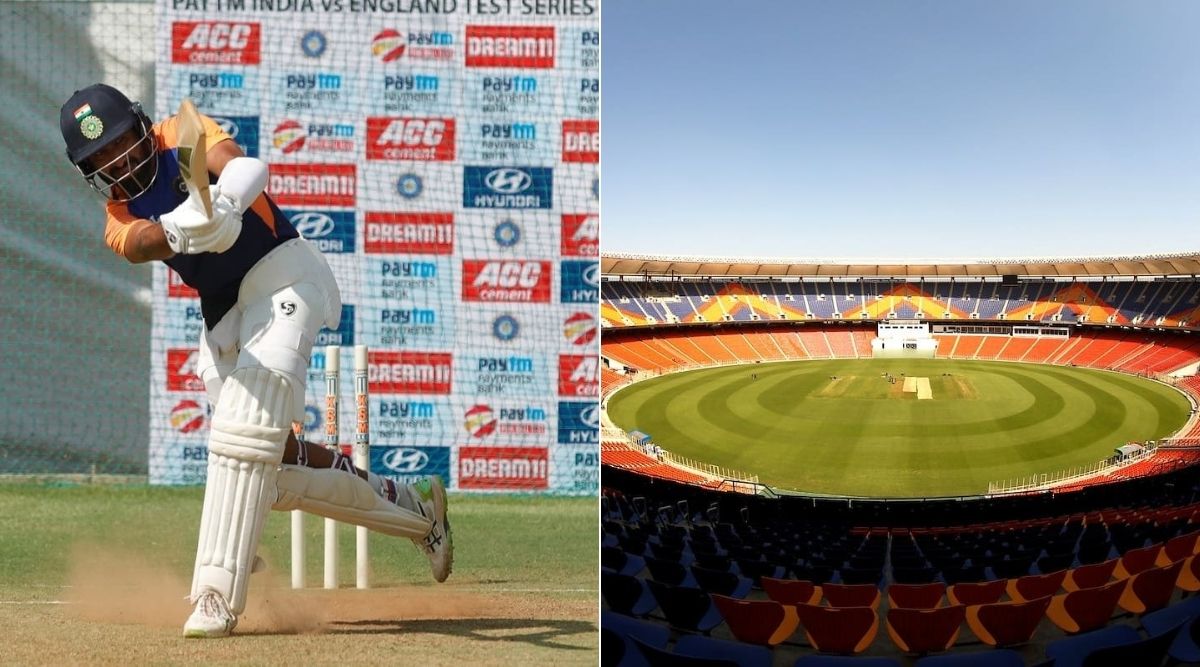

The surroundings in his return to Motera will be starkly different too. Once a nondescript, featureless stadium is now a modern-day colosseum. The Test will be played with pink balls and under lights—like Pujara, the game itself can meditate on the changes it was beheld in the eight years between Motera Tests. In many ways, it’s a leap into the unknown. No one knows how the pitch would behave or if there would be dew, whether the grass would be trimmed, or whether there would be spin and reverse swing. But all these unknowns make the match of an intensely-competitive series all the more engrossing. “With the pink ball, it’s difficult to assess. You expect something, but it could turn out to be something else,” he says.

But Pujara or the Indian team is not losing sleeping over it. “I don’t think it matters a lot when you play one-off pink-ball Tests, we will get used to it as we keep playing more. We’ll have to just play normal cricket, have similar game plans as we had in the previous Test match, depending on the pitch. We’ll just stick to that,” he says.

Neither do the memories of the last innings he played with a pink ball haunt him—the Adelaide Test. “In Adelaide, the ball was swinging around and we had one bad session of poor batting that led to that disaster, but overall if you look at the first innings, we were in a dominating position,” he points out.

Somehow, Adelaide 2020 seems far away, and Ahmedabad 2012 feels closer. Between Motera 2012 and Motera 2021. A lifetime of memories. A career fulfilled. A man contended.

Source: Read Full Article