Dalit artist Rahee Punyashloka, also known as @artedkar, on his first solo show in Mumbai

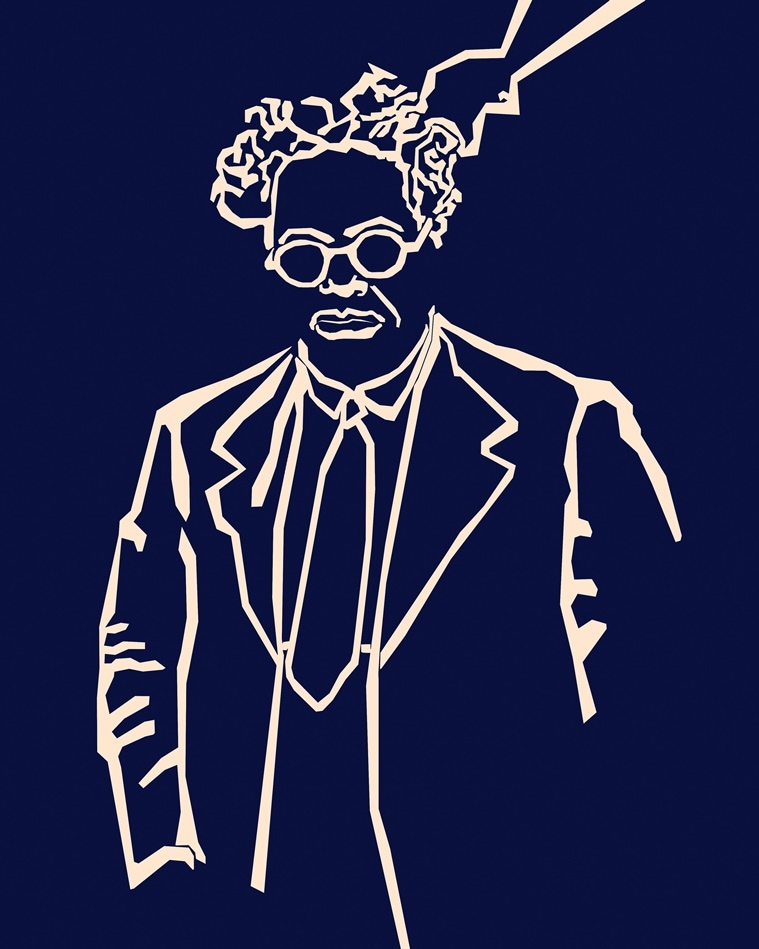

Stark ivory lines that swirl into fists, fingers and faces on an indigo background are synonymous with Rahee Punyashloka, 28. The artist is better known by his social media handle @artedkar, where his duo-chrome works memorialise and celebrate the Dalit resistance against India’s troubling caste practices. From this virtual showcase, the posts now have a physical presence, with Punyashloka’s first solo show of digital works at gallery Method in Mumbai.

“These works are like a bildungsroman. I choose moments from the history of Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi communities as well as those from my specific community. It’s how these moments have moved me or how I have learned immensely from them to reach the political awakening I have now,” Punyashloka says.

Based out of Delhi and Bhubaneshwar, Punyashloka trained in filmmaking. He has made experimental shorts, some of which were selected by international film festivals. As @artedkar, he presents his many observations as a Dalit artist, with both visuals and text, with both the past and the present – history and current events – at his disposal. He is also working on his first novel, A Manual for Shapeshifting, with the mentorship of author Madhuri Vijay under South Asia Speaks’ debut mentorship programme.

It’s no small coincidence that his exhibition opened on August 15. Method suggested to Punyashloka that since it was Independence Day, the show could highlight how several communities in India are yet to experience true independence. The artist is calling his show, which runs till August 26, “Séances, Featuring my Kin with Fantastically Large Shadows”. The title evokes the double meanings of “shadow”, he says. India’s caste system considered the oppressed castes as untouchable, a practice that is still very much prevalent in several parts of the country. The “lower castes” were impure, including their shadows. They couldn’t move about the town during the day, lest their polluting shadows fall on others. Punyashloka is also hinting at growing up in the shadow of the icons of Dalit resistance.

But it’s possible that we need none of these prefaces for a set of works that speak for themselves. The figure of the visionary Dr BR Ambedkar and vignettes from his writings are evoked often. The works are political, where even Ambedkar’s hair is indicative of a struggle against the caste system. As Punyashloka explains, Ambedkar’s messy hairstyles in his early years was because barbers refused to cut a Dalit man’s hair. He was forced to cut his own hair and the uneven results of his attempts were compounded by a receding hairline. It was only when he converted to Buddhism did he shave his head.

It’s not Ambedkar’s shadow alone that dominates the exhibition, however. One work shows Kantabai Ahire and Sheela Pawar, better known as the women who protested the discriminatory rules of the Manusmriti. In 2018, the two smeared black paint over a statue of Manu, the mythical figure who supposedly wrote the Manusmriti, that was placed outside the Rajasthan high court.

Punyashloka says that a lot of artists who inherit a history of pain and oppression tend to be angry in their art and there is an agit prop quality to it. “The moment you educate yourself of your histories, you do feel this agitation. But, Dr. Ambedkar’s call to “Educate, Agitate, Organise”, which is embedded in his decision to quit Hinduism in favor of Buddhism, is a thoroughly existential strategy. The final step is to contain the agitation, the anger, within yourself even as one feels it. It’s a baptism by fire, but the end product is never to prolong the pain,” he says. In one work, Savitribai and Jyotirao Phule are seen together; between the couple is a certain coyness and respect. The Dalit leaders, as revealed through letters written by the wife to her husband, were known to have a deep love between them, perhaps as constant as their social activism.

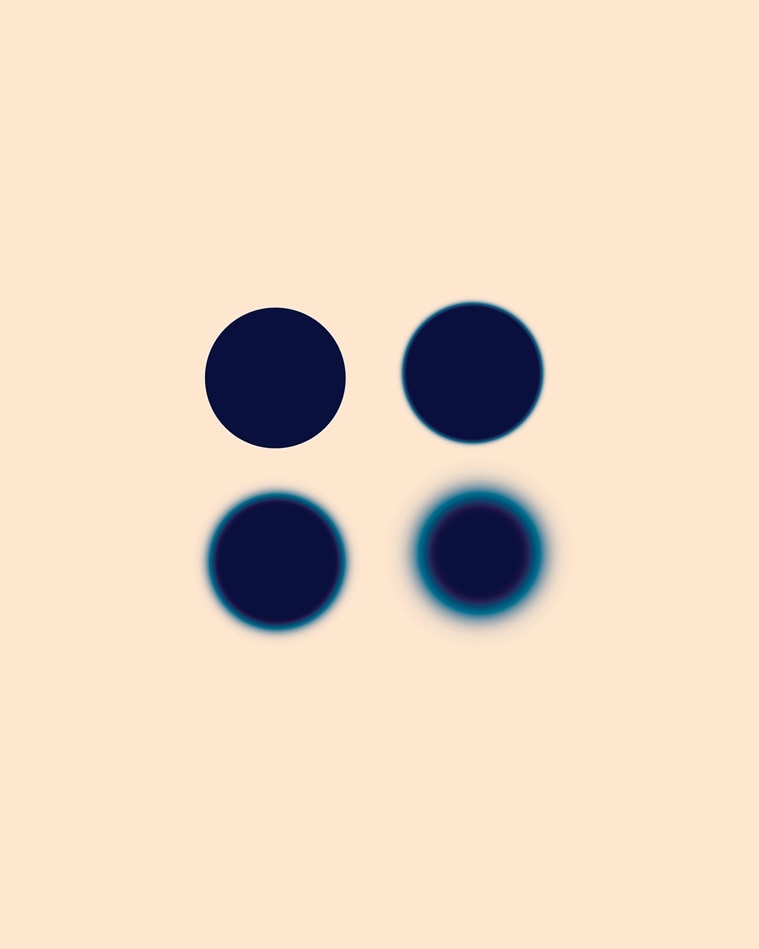

One work, probably the most abstract in the exhibition, inverts the white-on-blue approach. We see four indigo dots, with varying sharpnesses of margins, on a plain surface. They could be blood, they could be water but if one asks Punyashloka, he explains that they connect to his community of a dhobi, as stated in his caste certificate. The dots, usually made on the corner of clothing and linen, relate to a code that dhobis follow to mark the address and names of their customers. Punyashloka calls it “organic intellect” and coding by “dhobi ink”.

None of the works in the exhibition are for sale. Their purpose is something else altogether. The figures in the works are part of Punyashloka’s agenda to form a repository of images that can be identified as “Dalit art”, to overcome the gap in the visual language of Dalit and oppressed communities in mainstream art history.

Given a chance, Punyashloka believes he could make canvas works with “dhobi ink”. Even the use of the blue in his digital works, a colour strongly associated with the Ambedkarite movement, was just waiting to be picked up, he says. “It is iconic and inevitable. If not me, then it would have been any other Dalit artist.”

The exhibition is on till August 26.

Source: Read Full Article