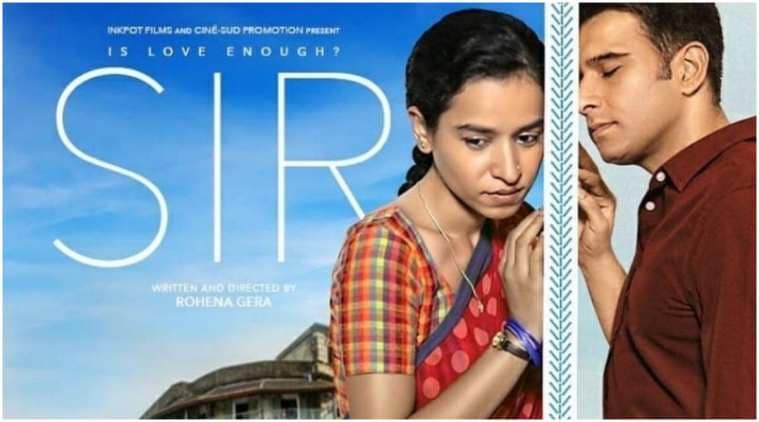

With Is Love Enough? Sir, Rohena Gera desists viewing togetherness as love’s end goal, gently uncovering the gifts of being in it instead.

Love thrives in conflict. Turbulence of any kind–social, cultural, communal–serves as an impetus. In a way, if love’s biggest incentive is togetherness then its purest purpose is to upend all hurdles which prevent that. The velocity and effectiveness with which this is done approximate the intensity of the emotion itself. It is this twisted assumption which sustains the premise of star-crossed lovers as the most familiar trope to be rallying for. That there are so many reasons for two people not to be together makes their union so gratifying. Love then is the last stop where all discord ceases to be. It is both the trigger and the shield, the reason and the purpose, the beginning and the conclusion. This alone makes Rohena Gera’s Is Love Enough? Sir — an uplifting and heartbreaking film revolving around the unlikely bond between a house help and her employer— a love story for the ages. For conflict thrives in inequality.

When we meet Ratna and Ashwin (Tillotama Shome and Vivek Gomber) they are already together. He curtails his trip, she cuts short her maternal visit. They stay at an upscale apartment in Mumbai. But there exists an island between them. She is a house help, her role in the house restricted to labour. The entire space belongs to him, she has put together her world in a small room. He watches French films and she consumes Hindi serials. He looks at the city from his verandah, she observes it from the terrace. Mumbai brought him back under compulsion and fettered him. She fought to come here and found an identity. He has free pass to places she longingly looks from outside. Their chosen tongue differs. The only two words she shares from his lexicon denote acknowledgement and subservience: thank you and sorry. He has ten different ways to call her, she has only one: sir. Silence fills in the space.

Yet there are more similarities between them than they would know. She is a widow and he has just called off his marriage. Both are bound by their duties as siblings. She pays for her younger sister’s education, he has come back from New York to take care of his ailing brother. Both have been afflicted with loss. The house, though withholds different meanings for them, is their meeting ground.

In films, love is always deemed as a solution, its enoughness instinctively assumed and never questioned. As much as the poor girl and the rich boy, the upper-caste girl and the lower-caste boy are aware of their differences, they are emboldened by the conviction that being together will realign disparity, that they are equal despite their circumstantial dissimilarities. Thus, even though fuelled by inequality, love serves as an equaliser. The focus then is to find the other person to elevate the ordinariness of lives to the extraordinariness of a story.

Gera not just deconstructs this preexisting depiction but also constructs a new one. She resists conflating the plurality of individuals to the homogeneous entity of lovers, locating love’s core principle as shared acceptance and individual aspirations. There is not one story here. The people involved are living their own stories, especially Ratna who is at the heart of the film, lending her tone, if not her name, to its title. She does not bear the narrative burden to be a concept with the sole preoccupation to reflect social inequality, neither does she want to be rescued. Instead Gera (who has also written the screenplay) infuses her with dignity but mostly with desire.

We see Ratna not the way others see her but also the way she is: her ambition to be a fashion designer, her willingness to learn and her aspiration to become. Widowed at the age of 17, which implies definite halt in a woman’s life at her village, she did not succumb to fate but made something out of it. Unlike Ashwin she knows not all ends are endings. She tells him this one morning. This time it is Ashwin whose gaze lingers long after she has left. Even though he had always been kind and polite he also did not view her outside her service. That she had a life before this and has the desire to live her own way makes him see her differently. It makes him— and us— see her as a person. She holds on to this integrity even when both are in love and he, fortified by it, is ready to face the world on her behalf.

With Is Love Enough? Sir, Gera desists viewing togetherness as love’s end goal, gently uncovering the gifts of being in it instead. And by doing so pursues what it can lead to when struggles are not shared, and individual stories–and not the one crafted together–are extraordinary. The ending of the film, which cuts to the bone with its tenderness reserves the answer: love at its best is about finding the other person and at its most transcendental it is about finding oneself.

But love also thrives in hope. The film reveals its understanding of this by treating the unbearability of endings with the lightness of a new beginning. Till then love is enough.

(Is Love Enough? Sir is streaming on Netflix)

Source: Read Full Article