'UNESCO declared it as a world heritage site. Unfortunately, visitors do not gather the significance as there is limited connection with ancient religion and iconography,' says Dr Manjiri Bhalerao, associate professor of Indology at Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth

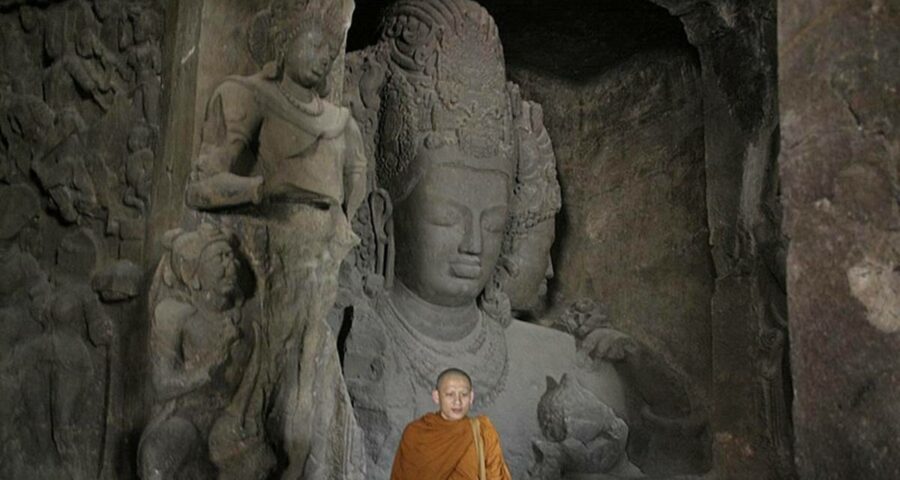

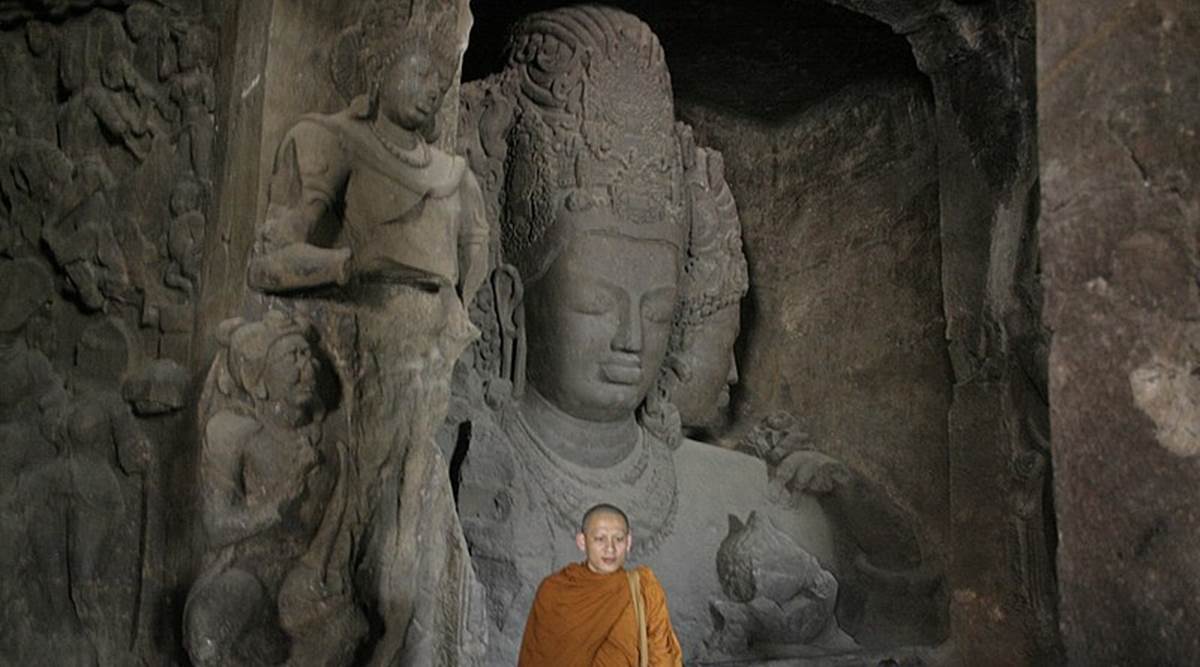

The six-metre monolith of the three-headed Trimurti Sadashiva, the primary attraction at Elephanta Caves, is so iconic, it has been immortalised as the official logo of the state tourism department. The colossal basalt rock structure is the depiction of Lord Shiva with three visible faces; the other two are left to the viewer’s imagination.

“UNESCO declared it as a world heritage site. Unfortunately, visitors do not gather the significance as there is limited connection with ancient religion and iconography. The Trimurti is misinterpreted by many, who think it is a representation of Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh, which it is not. In 1939, Austrian scholar Stella Kramrisch published an article on the Elephanta Caves, where she mentioned it is a Pashupata cave and a place where Pashupata sadhak (seeker) went to do his sadhna (meditation). Technically it is Trimurti — as you can see three faces — but then the interpretation is of Sadashiva, the omnipresent Shiva who has five heads and not three. Very few people actually understand the philosophy behind it,” Dr Manjiri Bhalerao, associate professor of Indology at Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, explains.

Bhalerao, who will be visiting the caves on January 19, elaborates the sculptures on the walls were carved not with an intention of visual art. Instead, the carvings were there to guide the sadhak or seeker who is on his path to salvation, according to the Pashupata traditions that draw from Lord Shiva.

“One of the stages of this religious, ritualistic and philosophical journey to salvation is to spend time in a cave. The sadhak has to understand the existence as well as the non-existence of the world. For example, the wall carving of the wedding of Shiva is not only a depiction of his marriage with Parvati, but it is the union of the father and mother of the world. Similarly, one needs to appreciate the sculptures and derive the apparent meaning. The sadhak follows the sculptures, pursuing the hidden meaning and in the end, after he leaves everything behind, all he knows is Parashiva, the ultimate truth in the universe at the sanctum,” Bhalerao says.

While the Trimurti is the manifest form of Lord Shiva, the un-manifest form is present at the sanctum, which is a Shiva linga. According to Bhalerao, it is here the journey of the sadhak ends, where he becomes one with his own God, that is Lord Shiva. “The caves depict the greatness and stories associated with Lord Shiva’s life but for the seeker, it holds a very different meaning.”

The reason why similarities can be drawn between cave 29 in Ellora and Jogeshwari in Mumbai, and the Elephanta Caves, is because of the same function in the ritual journey of the Pashupata sadhak, Bhalerao explains. “It was not art for the sake of art. The art created in ancient India had some functions attached to it, like religious, social, sometimes even economical and political context. The remains you see today are of religious monuments and some function can be associated with each, mostly to earn some merit or punya.”

The Elephanta island — roughly 10 km from the Gateway of India, and visited after a ferry ride — has two prominent hills: the Stupa Hill and the Gun Hill. The latter has the Pashupata caves.

The Gun Hill has a direct view of the jetty, an ideal location for bunkers and a huge cannon that dates back to the British era. On the other side of the island is Stupa Hill, which is not completely excavated. Old stair-like structures are used to visit the other end with a dam between the two hills constructed years ago.

Bhalerao says when the Portuguese reigned over the area, they used the caves for multiple purposes such as practising their shooting or having a safe space for cattle. It is believed a stone inscription was found by them, but today, it remains untraceable. “We still cannot really narrow it down to who created these magnificent caves but it is attributed to King Krishnaraja of the Kalachuri dynasty, a great Shiva devotee. Several tourists and visitors have found coins by King Krishnaraja, and therefore they think the caves may belong to that period.”

By the seventh century, according to an inscription, the area was a flourishing site with its multiple ports such as the Mora bunder and Raj bunder. “The latter seems to be the entry port for the royalty. The famous elephant stone sculpture after which the caves were named by the Portuguese is currently at Bhau Daji Lad Museum. Earlier, the island was called Agraharapuri, which later corrupted to Gharapuri,” Bhalerao says.

Although Bhalerao has visited the caves many times over the years, she is still mesmerised by the greatness of the artists who chiseled the stone sculptures.

“Every time you visit the caves, you learn something new about the artists. Sadly enough, none of these artists had their name mentioned. Instead, we come across names written by visitors. Tourism is both a boon and a curse and the preservation of the caves is at a 50-50 proportion. While the government, its bodies and expert tour groups make it a point to hold onto the heritage, several individuals visit Elephanta but miss out on the significance of the caves,” she concludes.

For more lifestyle news, follow us: Twitter: lifestyle_ie | Facebook: IE Lifestyle | Instagram: ie_lifestyle

Source: Read Full Article