The Great Indian Kitchen has the arc of an inspirational story where the inherent reward resides in watching an individual break free from all the odds stacked against them.

I can recognise my mother’s bare hands in a crowd: her nails unevenly broken at the sides, their colour blanched and her palms dipped in a tinge of yellow. Like she secretly carries turmeric in them. This is an enduring image, also a familiar one. All elderly women in my household, my aunts and now my sister married for over a year, have hands like these. Growing up when Ma came to bed to put me to sleep and rest, she would place her palm on my forehead. I still remember that smell– a stifling admixture of food and detergent, so different from mine like we had separate meals. That nagging whiff remains as if all soaps in the intervening years had conceded defeat. In more than one instance in The Great Indian Kitchen, the newly-married girl smells her hand after cooking and swabbing the floor. A faint sense of disgust betrays her face. She says nothing but I knew what it smelt like.

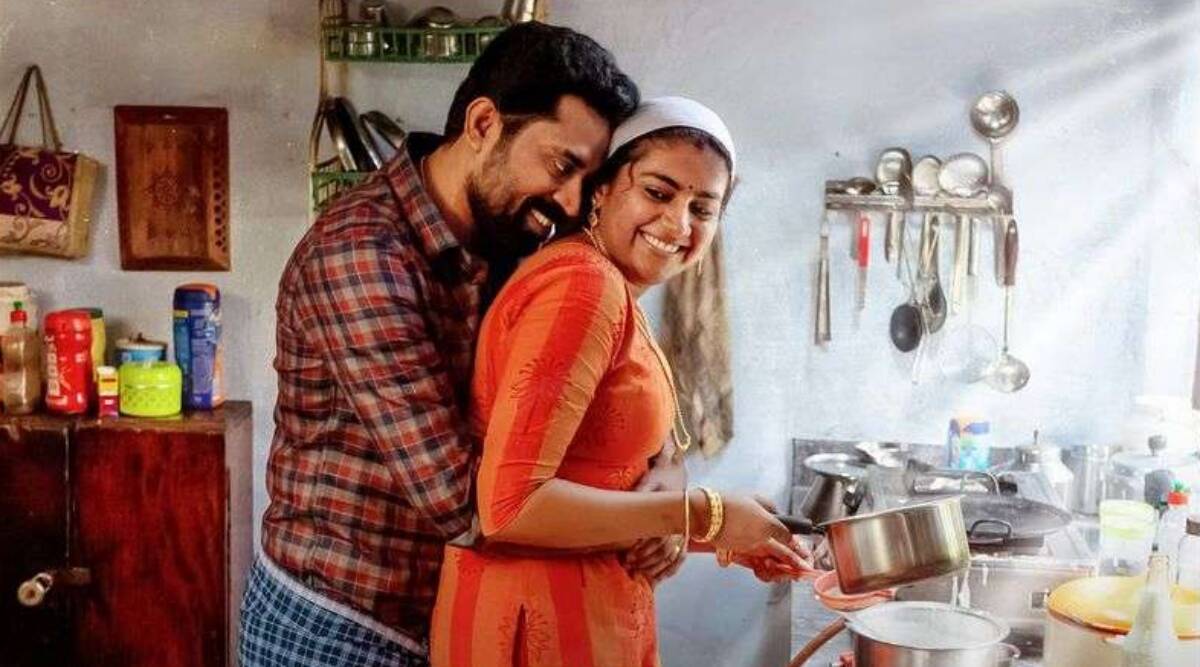

Jeo Baby’s film opens with a great Indian wedding. A couple (Suraj Venjaramoodu and Nimisha Sajayan, none of them is named in the film) is hitched through an arranged set-up. Her husband is smitten and in-laws are far from demonic. Her mother-in-law is particularly caring and kind. It is her absence that puts all pressure squarely on the protagonist. Days begin with preparing breakfast, cleaning tables and afternoons are spent making lunch. The ritual is repeated for dinner. Initially her husband eats at the office canteen but he would prefer carrying tiffin from home. He informs her over the phone, not as a complaint but neither as a request. She agrees. Her father-in-law would prefer it if she grounded masalas by hand and not used the washing machine, especially for his clothes.

A premise such as this is nothing out of the ordinary. In fact, The Great Indian Kitchen could as well have been about two strangers falling in love after marriage. But in such arrangements, it is the emotional upheavals, initial awkwardness followed by growing proximity, which is considered as the only offshoot, especially for women. Jeo departs from this by underlining the unspoken jaggedness embedded in a marriage suffered by women alone, emphasising on the impossibility of depicting their emotional toil without acknowledging its constant counterpart: physical labour.

He does so by unsparingly documenting her every day. Her rush to the kitchen to fetch hot dosas, the precarity with which she holds several things in her hands, her eyes darting from the crowded basin to the plate of vegetables waiting to be chopped. It is like every being of her body has been trained to an unspeakable sense of haste. All of this occurs while her father-in-law leisurely reads his morning newspapers in the courtyard, her husband practises morning yoga and both leave their dirty dishes on the table.

None of these is an exaggeration. I have grown up watching men in my family sitting first to eat without the least hint of hesitance, devouring the biggest piece of chicken like it is their birthright, and framing rules of the house like no one existed other than them. At every get-together, I see them summoning their wives and with a child-like helplessness asking about clothes. But they are also the most gentle men I know- respectful towards elders, never raising their voices, discussing instead of arguing. Growing up I wanted to be like them. You see entitlement is addictive. My decision to leave my hometown with an unsaid urgency and stay alone was informed by my stubborn refusal to be like my mother. For close to five years I would dump my clothes in a bin and go to the office only to find them washed and folded later. I refused to enter the kitchen or learn cooking. Just like my father. When I visited home it was his advanced age and difficulty to cope with it that troubled me. His struggle saddened me. Ma was always in the background waiting for a new audience for her old stories.

This changed during lockdown. Like everybody else I was left to myself to do all chores. I do not remember exactly when but after a while my hands started smelling like hers. I was repulsed. I kept washing them but the smell returned. One evening my nail broke doing the dishes and when I called Ma with a lump in my throat to tell her about my burnt hand (the mark remains), it dawned upon me that after years of resistance I have become like her. Disgust gave away to a deep sense of shame.

The invisibility of her labour and its unbearable weight opened up before me with a blinding jolt. Suddenly I was just not aware of everything she has done all these years but the extent of it and mostly the thanklessness with which it was always been received. For years whenever we were supposed to go out, Ma would be the last person to get ready. Before the Uber-era, Baba would get a taxi. I remember without fail how Didi and I would stand in the balcony, keeping a watch for the yellow vehicle. We knew the rising meter was equivalent to Baba’s rising temper. It is like a short film that always played on loop: Ma hurrying from one room to the other, checking the gas, bolting the windows and me running after her with the sari.

This haste manifested in not getting time to find a matching blouse or forgetting to wear earrings. Even after all these years Baba regrets Ma’s inability of getting ready in time and imbibing no shred of his discipline. When I grew up a little I started echoing him. Really, how long can some habits last? Only lately, as late as 28 years did I realise she took that long because her work never ended. Our collective blithe assumption of Ma knowing everything in the house weighed down on her, it still does perhaps. She knows because none of us make any effort to. Our love is her labour.

This continuous, supposedly invisible physical labour is allocated on the basis of gender. Entitlement, contrary to what I had naively assumed, is not inherited but bestowed upon. And though for some women it is more easily accessible than most, we win even by losing. Faces in the kitchen might change but but the assumption from the gender to be there remains the same. Away from family when I was not doing my chores someone else, a woman, was doing it for me. She had replaced Ma till I replaced her. The contrarian argument could as well be that the lockdown was democratic when it came to such labour but the rebuttal, one that I felt in my bones is contrary to a man, a woman enters a kitchen to never leave. I knew it was a compulsion so I treated it as a choice till I could.

And this is where the recent Malayalam film really excels– in its understanding of the viciousness of this gendered cycle. The Great Indian Kitchen has the arc of an inspirational story where the inherent reward resides in watching an individual break free from all the odds stacked against them. Bigger the barrier, the greater is the triumph of overcoming it. The intrinsic characteristic of such a narrative is the possibility of the change it withholds, the solution it offers. The idea is that the person who breaks the glass ceiling also shows others the way to do so.

Even though the film plays out like this, heightening —not exaggerating— the abuse with the inclusion of religion, the “solution” is hardly feasible. The structure then is a conceit. But Jeo chooses to use it for the same reason I have found it convenient to write about my father, and not my mother in the past. Stories are about those who got away, life is about those who stayed.

(The Great Indian Kitchen is streaming on Neestream)

For more lifestyle news, follow us: Twitter: lifestyle_ie | Facebook: IE Lifestyle | Instagram: ie_lifestyle

Source: Read Full Article