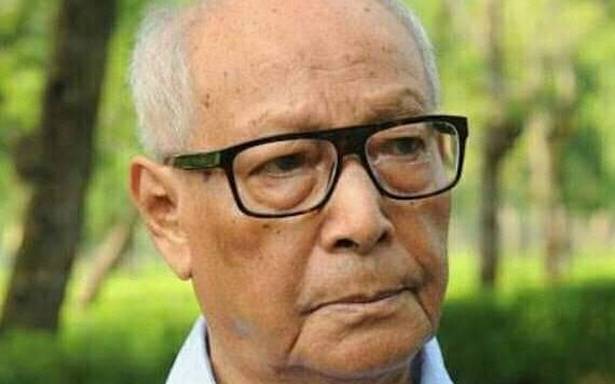

On May 12, 2021, the Assamese lost one of their guardian angels. In tributes and condolence messages flowing in from all sides, Homen Borgohain (1932~2021) has been referred to as a ‘batabrikkha’, a revered banyan tree that sustained an entire ecosystem of readers, writers and literary enthusiasts, now uprooted.

One of the foremost intellectuals of Assamese literature, Homen Borgohain has left for his heavenly abode. An eminent journalist also, he was an inspiration to writers and journalists in Assam. My heartfelt condolences to his family, friends & followers.

Having lived not just a moderately long life, but a meaningfully productive one, Borgohain has left behind a massive body of work. He has to his credit five collections of short stories, thirteen novels and novellas, around fifty volumes of non-fictional prose, four books that are autobiographical, several edited volumes, and a single book of poems titled Hoimonti (1987). He won the Sahitya Akademi award in 1978 for his novel Pita-Putra (1999) but returned it in 2015 in protest against the Dadri lynching. Two of his other notable books of fiction, namely Matsyagandha (1987) and Halodhiya Soraiye Baodhan Khai (1973) were made into feature films, and the latter, directed by Jahnu Barua, won the national award in 1988. His Subala (1963) is notable not just for being the first ever work in Assamese literature on the life of a prostitute but also for being a decisive point in the development of post-war Assamese fiction, in the same rank as Birinchi Kumar Barua’s Jibanar Batat (1945) in waking up Assamese fiction from its long hibernation.

An esteemed journalist known for his thought-provoking and razor-sharp political writings, he was the founding editor of many weekly magazines like Nilachal (1968), Nagarik (1977), Samakal (1987), Sutradhar (1989). He also served as a special correspondent at the Calcutta-based daily Aajkaal, his work featuring in its North-East section, for a few years from 1981, where he wrote many pieces and was the first person from Assam to interview Mrs. Gandhi at length.

In his own words, he studied each day of his life like a student who was preparing for his exams. When interviewed, he put it thus: "I write two hours and read for two hours every day." This, in addition to the work he did in the capacity of a chief editor for various dailies, weeklies, and monthlies throughout his life. There is a word of Bengali origin in relation to music, ‘riyaaz’ — a constant honing of one’s musical skills. Borgohain did that to his writing because he knew it required constant sharpening. To him the act of writing was what we call in Assamese neerab sadhana — quiet meditation — and he practised it rigorously, regularly and religiously so that the gift never left him.

Hailing from the remote and backward village of Dhakuakhana in the Lakhimpur district of Assam, Borgohain was an example of what a man of humble origins and unexceptional looks (it made him suffer from inferiority complex during the Cotton College days as mentioned in his immensely popular autobiography Atmanusandhan) could achieve. He was an inspiration to generations of Assamese youth in the latter half of the twentieth century and beyond, most of whom forayed into the world of reading with his books. On his death, the Assamese as a people are almost chanting in unison, “He introduced us to the world of books. Our love for literature began with reading him.” Not that the Assamese did not read before him, but the range and habits of reading changed substantially, a new reading public emerged from the lower and lower-middle classes.

A voracious reader himself, he did in the world of Assamese letters what the medieval saints did to the sacred texts by translating them from classical languages to regional ones, thus decoding these for common people and making knowledge open to all. Borgohain popularised the form of the personal essay in Assam, and applied his wealth of reading into these pieces, combining personal experiences and moments of introspection with allusions to and anecdotes from the worlds of literature, philosophy, civilisational history, etc. The 154 personal essays collected in the three volumes of Mor Tokabahir Pora (Pages from My Notebook) have reserved their due place in the canon for posterity. The index of contents from one of his earliest collection of nonfictional prose called Ananda Aru Bedanar Sandhanat (In Search of Joy and Sorrow) introduces the masses to names like Jorge Luis Borges, Edgar Lee Masters, Goethe and Charlotte von Stein, Heinrich Heine, Dag Hammarskjold. He was not the intellectual’s writer (although he had everything that it took to be one) but the people’s writer. Like capsules, he packed knowledge in the simplest of forms, making it accessible to the masses, that too in a pre-Amazon and pre-ebooks era when not just readers but even bookshops were numbered.

Borgohain had a gift for spotting fresh or obscure talent — and not just spotting but encouraging them onwards. Despite his busy schedule, he took time out to draft letters of appreciation to these young minds, sent for them from his office, or rang them up asking them to submit work. He provided platforms to new and emerging voices, put his faith in writers whose works were turned down by other leading magazines that played it safe by only publishing trusted and revered writers. While it is not unlikely that a senior and experienced writer anywhere in the world would help or guide aspirants in that field, what sets Borgohain apart from all of them is the sheer number of people he had helped take flight. In Assam at present, be it established or struggling writers, or journalists, academicians or intelligentsia, there may be few who, at one point or the other, had not been mentored by him or taken him as a role model. That measures the magnitude of the Borgohain effect.

Immediately after the news of his demise spread, an old video of the stalwart has resurfaced, and has been doing the rounds, widely shared and forwarded in social media platforms. It is an interview where he is heard saying, “Till my last breath I will keep labouring hard. Just as you extract the juice out of sugarcane until only the bagasse remains, I will work till the last drop of life is strained out of me so that when I discard the mortal flesh I am no more than bagasse [translation mine].” And so he did. He remained active as the editor-in-chief of the Assamese daily Niyomiya Barta until his death, caused by post-Covid complications. What the Assamese as a race should remember and emulate is Homen Borgohain’s proclivity for hard work.

I would like to end this write-up with my translation of one of Borgohain’s poems, ‘Smriti’ (Memory); more often than not death and art reveal their true merit only retrospectively.

(Here is a list of Homen Borgohain’s writings in English translation for those who do not read Assamese)

· The Collected Works of Homen Borgohain; translated by Pradipta Borgohain, Amaryllis, 2017.

· Astorag (Sunset). Translated by Ashok Bhagawati, Sahitya Akademi, 1996.

· The Field of Gold and Tears; Translated by Pradipta Borgohain, Spectrum Publishers, Guwahati, 1997.

· Pita-Putra (Father & Son). Translated by Ranjita Biswas, National Book Trust, 1999.

· Image and Representation: Stories of Muslim Lives in India; Edited by Hasan Mushirul and Asaduddin M. (contains his story “In Search of Ismail Sheikh”), OUP, 2002.

· The Muffled Heart: Stories of the Disempowered Male (2005) translated by Jayita Sengupta.

· Asomiya Hand-picked Fictions selected by the North East Writers’ Forum (containing his story “In Search of Ismail Sheikh” tr. by Pradipta Borgohain), Katha, 2003.

(Written with inputs from Bijit Borthakur)

Source: Read Full Article