In 1966, he left for Copenhagen to train in furniture design at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, worked with Poul Kjærholm, and a host of other designers during the golden period of Danish design.

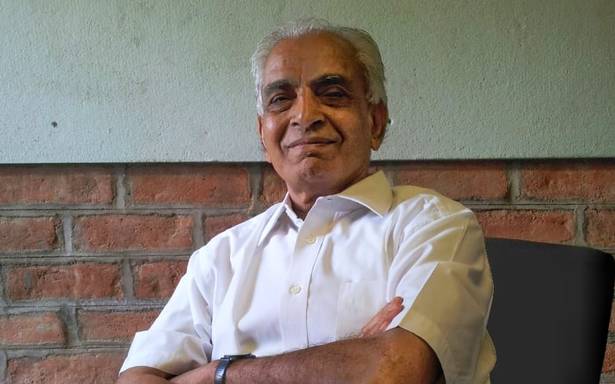

In 2018, when I last met Gajanan Upadhyaya, he was as full of enthusiastic energy as in the 1980s when I was a student at the institute. He quizzed me in that inimitable way of his, ‘But you are not a furniture designer, you are a communication designer, why have you come to ask me about my chairs?’. As quickly and without waiting for my reply, he proceeded to explain the details of the particular chair he was holding up.

It was at the National Institute of Design, NID, that furniture design as a formal discipline was first established in India. The founding visionaries of NID, Gira and Gautam Sarabhai, were integral in bringing in national and international creative professionals to guide the early years of the institute, and Upadhyaya was one of the first Indian recruits. The ethos of ‘learning by doing’, on which the curriculum was largely based, resonated with GU, as he later came to be known, speaks of a childhood in rural Gujarat, spent working with his hands, from making simple slingshots to the more complex weaving of coir onto a charpoy.

Through the course of his career, he brought his initial training as an architect as well as the sensibilities he imbibed as a farmer’s son. In 1966, he left for Copenhagen to train in furniture design at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, worked with Poul Kjærholm, and a host of other designers during the golden period of Danish design. He returned to India in 1974 to teach in the NID furniture design department for over 20 years, contributing his designs to iconic furniture stores such as Taaru in New Delhi. Even after retirement he continued to keep his design skills alive by working as a consultant for the TDW Design, a furniture design firm in Ahmedabad.

GU’s non-narrative approach towards his work sought a Plato-like ideal; conversations about the prosaic—material, thickness, structure, and such—often turned philosophical. Ideas of robustness and anonymity spoke as much of his work as to his personality. GU’s designs were remarkably modern in thought and expression, despite his steering clear of political and ideological discourse around the Modernist movement. Distinct in the economy of material used, absolute in structure — his work was ‘pure’ and ‘honest’. His interactions with furniture designers such as the American Japanese George Nakashima, and Danish Hans Gugelot, both of whom participated in the workshops at NID, as well as his stint in Denmark, working alongside modern masters — furthered his sensibility towards a universal idiom. The 24/42 chair that GU worked on with Gugelot displayed his approach to an economy of material, while the Kornblut chair, he built with Nakashima, was as much a tribute to wood as it was poetic in form.

In 2018, his strides were as sharp and quick as his commentary on the finer details of furniture design, as he stepped over furniture pieces in the iconic prototype room at NID. Within his life, are lessons not just for the furniture students he taught but also the many other students, faculty and colleagues who had the opportunity to come in touch with him. Generations of designers are indebted to him and strive to emulate his work and life ethos. However, the absence of public recognition of GU-—who is reasonably called the father of Indian furniture design and who trained a host of Indian designers for close to half a century — is conspicuous and speaks as much to his personality as to his designs — solid, yet anonymous.

This is an adapted extract from a forthcoming publication on the seating culture of India, written and edited by Sarita Sundar and to be published in 2022 by Godrej Archives, Godrej & Boyce, Mumbai.

Source: Read Full Article