There is simmering disquiet in the Communist party and the world is watching as to what can unfold in China in the days to come ahead of next year’s party congress, notes Rup Narayan Das.

Exactly a hundred years back on July 1, 1921, twelve Chinese people congregated at a private girl’s school in a French enclave in Shanghai to sow the seeds of the Chinese Communist party which today has grown into a the largest political party of the world.

Its chequered history has witnessed many upheavals and has not only survived, but has become more robust and masculine.

A major survival instinct of the party has been its capacity to adapt to political and social dynamics and not bogged down by rigid dogmas of Marxism-Leninism.

In an unindustrialised society where peasantry and rural household were the mainstay, it creatively and successfully galvanised this stratum of the society and polity and slowly indoctrinated them.

In the initial period of its coming into being, it remained predominantly under Soviet control from 1923 to 1931.

Fully realising that the party on its own could not liberate the country from warlords, it forged a tactical ‘united front’ with the nationalist Kuo-min-tang of Chiang Kai-shek in the early period of its liberation struggle.

The first experiment of the ‘united front’ was terminated in 1927.

The Communist International or Comintern in short ousted Mao Zedong from all part posts for his failure to comply with the party line which forced Mao to retreat to the border between Jiangxi and Fujian, which became famous as ‘Jianxi Soviet’.

Mao established a rural base area there. It was here that Mao established his Red Army.

It was during this time that Mao formulated his dictum that “political power grows out of the gun, adding that the party must always control the gun instead of gun controlling the party.

That is how the seamless connection between the two organs grew over the years and got enmeshed in the persona of the party supremo.

The Communist party while consolidating its position, forged the second ‘united front’ with the KMT.

The internecine civil war, however, continued till the victory of the Communist party in October 1949.

On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong rode through the streets of Beijing in a captured American jeep, ascending the rostrum at the infamous Tiananmen Square, proclaiming the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

The world had to contend with what Napoleon said about the Celestial Empire, ‘Let China sleep, for when she wakes up, she will shake the world’.

Be that as it may, China after its birth got entangled both internally and externally with a myriad of problems.

The radical reforms that Mao introduced like mass collectivisation of agriculture, handicrafts and private commerce had their flipsides, while land reform was popular.

There were criticisms and resentment domestically. To obviate the headwind Mao launched his campaign, ‘Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom; Let a Hundred Schools of Thought Contend.’

Although scholars sympathetic to Mao ascribe that Mao himself, based on his conviction that criticism would strengthen socialism since in the end truth wins out; the campaign was a euphemism for a power struggle.

Externally, China was embroiled in the Korean Peninsula, when war broke out there in the early 1950s.

The ‘Hundred Flowers’ campaign didn’t yield the desired result that China could gradually move towards socialism.

This impelled the Helmsman Mao to launch ‘The Great Leap Forward’ in 1958 exhorting people to toil hard so as to catch up and overtake industrialised countries of the world. The consequences were disastrous.

The high point of China’s projection as a major Asian power was the Bandung Conference 1955, thanks to India’s proactive role.

Before the dust could settle in the Korean Peninsula, the Sino-Indian border war broke out in 1962, which plummeted the relationship between the two countries to its lowest point.

It is not a coincidence that during this period there was an internal power struggle going on in China.

Mao started the ‘socialist education movement’ during this period between 1962-1966.

This was followed by the tumultuous ‘Cultural Revolution’ which started in 1966 and ended in 1969.

As the turmoil of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ ended, normalcy returned to China both domestically and externally.

The Tenth Party Congress, held in August 1973, witnessed the rehabilitation of some leading pre-Cultural Revolution leaders, including former party general secretary Deng Xiaoping.

With Mao’s death in September 1976, an era of China’s chequered history came to an end.

China became a member of the United Nation in 1971 replacing Taiwan.

Externally with the signing of the Shanghai communique a year later in 1972, its relationship with the USA was also rechristened, although the formal diplomatic relations were established in January 1979.

With the restoration of the relationship with the USA, Deng also ushered his economic reforms and liberalisation in 1978.

By the time the third plenum of the Communist party’s eleventh central committee was held in December 1978, the extent to which Deng had been able to exert his power was evident.

At the plenum Deng also reintroduced his pet ‘Four Modernisation’ programme consisting of modernisation of industry, agriculture, science and technology and national defence.

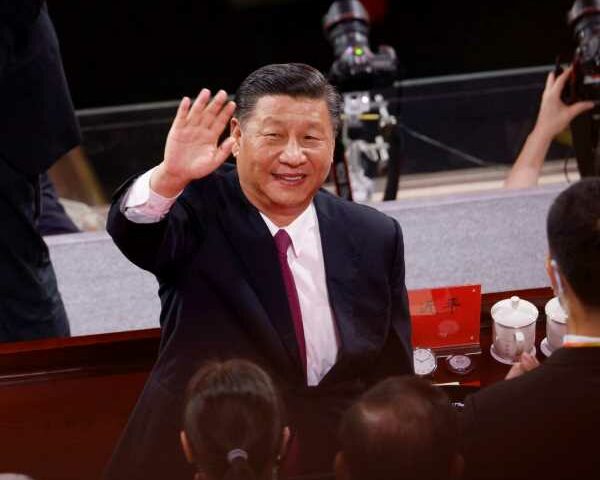

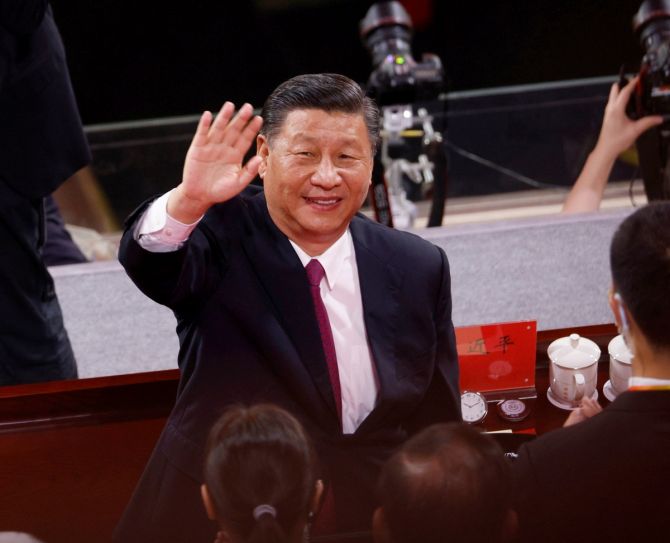

After Deng, who passed away in February 1997, Xi Jinping is the most powerful leader in China.

Xi is the first top leader born after the birth of the People’s Republic of China. He grew up in the tumultuous history of China in the post-liberation years.

He is, what is called in China a ‘princeling’, the son of top Communist Party leader Xi Zhongxun who suffered during the Cultural Revolution.

Xi came to power in 2012. The 19th party congress in October 2017 consolidated his full grip not only on the party but also on the entire edifice of the Chinese State.

There is simmering disquiet in the Communist party and the world is watching as to what can unfold in China in the days to come ahead of next year’s party congress.

Dr Rup Narayan Das is a China scholar and currently a senior fellow at the Indian Council of Social Science Research at the Indian Institute of Public Administration, New Delhi. The views in this column are personal.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article