I got to know that every referred case for angiography and angioplasty got a kickback of Rs 5,000 and Rs 15,000 respectively.

Seeing this trend, doctors started paying referring doctors Rs 1 lakh in advance and adjusting it as and when patients came in.

This menace slowly spread its tentacles all over the medical field, including radiological diagnostics and biochemistry laboratories.

For every test ordered, 20 per cent of the bill was given back to the referring doctor.

This led to doctors recommending unnecessary tests.

The pharmaceutical companies also saw burgeoning business.

Acclaimed doctors were given televisions sets, refrigerators, air conditioners and cars depending upon the prescriptions.

General practitioners would prescribe unnecessary drugs, and were given returns in cash.

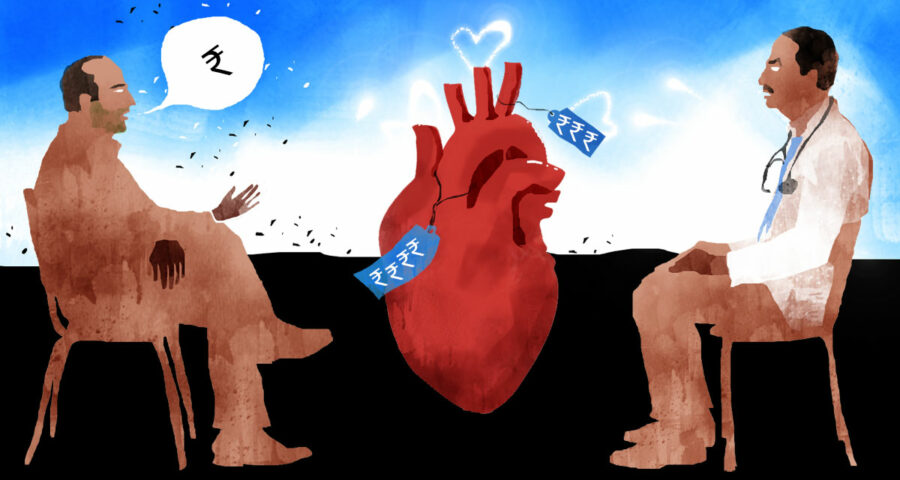

A fascinating excerpt from Dr Upendra Kaul’s When The Heart Speaks.

Dr Upendra Kaul, a trailblazer in interventional cardiology in India, is the chairman and dean academics and research at the Batra Hospital and Medical Research Centre, New Delhi.

Dr Kaul trained in New Delhi and Australia and has held prestigious positions at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, G B Pant Hospital, Delhi, Batra Hospital and Fortis Health Care, Delhi.

In his memoirs When The Heart Speaks, Dr Kaul recalls his childhood and family life in Kashmir and his innings as a senior cardiologist, known for his skills in elaborate, ground-breaking cardiac procedures.

In this revealing excerpt from When The Heart Speaks, Dr Kaul highlights disturbing practices at private cardiology hospitals in New Delhi.

During my 40-odd years of clinical practice in Delhi, I was witness to the changing patterns in patient care by medical and paramedical staff from the pharmaceutical and device industry.

Till the middle of the 1990s, things were reasonably in order and the medical fraternity was in general held in very high esteem. The doctor was regarded as ‘next to God’ by patients and their families.

Referral patterns were straightforward and the doctor used to do it in the best interest of the patients without expecting any returns, except for feedback regarding their welfare.

The kickback, at best, would be in the form of free registration for a continuing medical education programme or help in the registration and accommodation of students during conferences. Doctors would also distribute free samples of medicines to needy patients.

My first encounter with the changing system was within a year of my joining Batra Hospital in 1997. I was referred to a few patients by a practitioner from Jabalpur, all of whom needed angioplasty.

My team and I did it and kept our Jabalpur colleague informed about the outcomes and procedures, including the follow-up treatment. The patients were sent back to him in a few days.

A few months later, the doctor called up to say that he was coming to Delhi and would like to meet me. I told him he was always welcome and asked him to come over. He reached my office on the appointed day and we talked about his practice, his city and I asked him if he would be interested in having lunch together.

He refused the offer and said, ‘No, I just came here to offer my namaste.’ I was a bit taken aback, but still folded my hands and said, ‘Namaste’ and stood up to leave.

He got up too and said, ‘Wait, what about my share?’

I turned around and said, ‘Share? About what?’ Apparently I was a simpleton without any grooming of what happens in the field.

He looked at me arrogantly and showed me a list of five cases he had sent me and demanded a sum of Rs 30,000 as his share.

I was stumped for a moment and then became furious. Never in my professional life had I been asked for money in this manner; neither have I ever demanded from anyone too when I referred my patients.

I stared at him coldly and said, ‘I don’t owe you anything. And never, ever disgrace the profession like this. Please leave before I call security.’

The colour rose in his face as I said this. Some people had assembled around us too and it was becoming an awkward moment. He looked around and then slunk off to the nearest exit. He never called or referred cases again.

This was my first exposure to this new business.

A new hospital had come up in Noida around the same time. The owner was a cardiologist with moderate skills. The hospital started doing very well and secured approved government empanelments, such as the Central Government Health Scheme, Ex-Servicemen Contributory Health Scheme, etc.

I soon realised that our referrals from physicians started falling in numbers. On trying to find out the reason and reviewing our success rates, I got to know that every referred case for angiography and angioplasty got a kickback of Rs 5,000 and Rs 15,000, respectively.

In fact, seeing this trend, the doctors went a step further and started paying their referring doctors Rs 1 lakh in advance and adjusting it as and when patients came in — an ingenious move.

This menace slowly spread its tentacles all over the medical field, including radiological diagnostics and biochemistry laboratories. For every test ordered, 20 per cent of the bill was given back to the referring doctor.

This led to doctors recommending unnecessary tests. The pharmaceutical companies also saw burgeoning business.

Acclaimed doctors and specialists were given freebies, such as fancy televisions sets, refrigerators, air conditioners and cars depending upon the prescriptions.

General practitioners would prescribe unnecessary drugs, multiple kinds of vitamin supplements and specific brands of drugs, and were given returns in cash. Very often, prescriptions were written in codes which could be deciphered only by specific chemists.

Over the years, the priorities of cardiology students also changed. I stood witness to the change happening over the last three decades. Between 1980 and 2000, the number of seats was limited and both consultants and residents were very committed despite the overwhelming clinical work.

Punctuality was the rule. Teaching institutions were mainly confined to government medical colleges in Delhi and AIIMS. There was no strict selection criterion and only students interested in learning applied for postdoctoral teaching, like a DM in medical specialities like cardiology, neurology and gastroenterology.

In surgical specialities, it was cardiothoracic and vascular surgery, neurosurgery and paediatric surgery. Other specialities got added later.

With the growth of specialities, the need for good specialists increased. The selection of candidates for post-MD specialities has become very competitive and there is a robust selection process for getting admission.

However, the standards of teaching have been very variable. In general, the teaching institutions like AIIMS and PGI Chandigarh have maintained the standards.

Private institutions, in general, do not have the same motivation. The faculty spends very little time in reading and keeping abreast of new developments. The motivation of postgraduate students has evaporated. They are only reading to pass the examination and are not interested in writing scientific papers and case reports. They try to find shortcuts for making presentations at seminars.

The same is true when patients have to be investigated and prescribed drugs. Patients are now known by their bed numbers and not by their names. The consultant’s ward round is more often a ‘treatment checking’ round and it is often revealed that the patients’ complaints are frequently not addressed. Residents are only conscious of their duty hours.

There is a definite need for more specialists in various super specialities in the country where the burden of non-communicable diseases has increased to alarming proportions.

There has also been a boom in the number of cardiology clinics, echocardiography and cardiac catheterisation laboratories throughout the country. Even smaller cities and towns have these centres.

While Delhi has more than 100 invasive cardiology centres, neighbouring places like Faridabad, Narela, Karnal, Sonipat, Panipat, Hissar, Rohtak, Mathura, Agra, etc have these facilities too.

Gurgaon (now Gurugram), Ludhiana, Jalandhar, Pathankot, Amritsar have become hubs with several big cardiology centres. Most of them are private enterprises and are doing quite well.

The downside is that there is no auditing, no appropriateness criteria stipulated by authorities, and it is a general impression that unnecessary and uncalled for procedures are being performed. These not only include diagnostic angiographies but also angioplasties and putting stents in non-critical cases which only need good evidence-based medical treatment.

The same is true of device implantations like permanent pacemakers. These uncalled for procedures are not only ethically wrong, but sometimes cost the life of the subjects because of clotting of stents and infection of devices, and lead to a lot of morbidity for these unfortunate subjects.

I know from personal experience that patients were being charged for coronary stents when no stent had been implanted.

One such case was referred to me by a state government for verification. The patient was subjected to angiography and following that his relatives were told that one of his three arteries has a critical blockage. He was advised immediate angioplasty and putting in a stent.

It was a government hospital and the doctor took money for the stent in cash. He went ahead and seemingly did a procedure in the laboratory. Following the procedure, he also handed over the box of the used stent to the family.

The news leaked out of the lab that no stent was put in. The patient’s family complained to the medical superintendent. The cardiologist defended himself and maintained that he had put in the stent.

The case was referred to me a few years afterwards. The original angiography records from the hospital went missing under mysterious circumstances.

I decided to do an angiography. Normally a stent is visible in angiography. I could not see any. In spite of this, I did a procedure called intravascular ultrasound to make sure because some stents are very thin and not well seen.

IVUS also confirmed the absence of a stent. In spite of my written report, no action was taken against the doctor. He took long leave and went to the US.

The patient ultimately filed a case in court and I was summoned as a witness a few years ago. The doctor pleaded that it was an absorbable stent and hence was not visible.

Absorbable stents had come in the market after several years of this procedure. These arguments still didn’t lead to any action being taken, even 20 years after the incident. ]

Obviously, the doctor was very well connected with the high-ups. (The perpetrators of) these incidents can only go scot-free in our part of the world. We need to have serious and rapid redress of such important issues.

There is an unmet need of having more trained cardiologists in our country. As per the figures from the Cardiological Society, we have 4,000 registered cardiologists with a paltry ratio of one per 300,000 population as compared to 23,000 in the US, giving a figure of 43.8 per 100,000.

The other issue is the quality of training, which varies a lot. It depends upon the institution which is imparting the training.

The authorities imparting training are the universities offering post-doctoral programmes called Doctor of Medicine and the hospitals without attached medical colleges were recognised by a central government body called the National Board of Examinations and were allowed to pursue a post-doctoral degree course called Diplomate of National Board which is equivalent to DM in a speciality.

Both are after postgraduation in medicine or paediatrics. The training of DM cardiology is more thorough and focusses on all the aspects. The focus of DNB imparted in private institutions invariably is on procedures like echocardiography, angiography, angioplasty and device implantations. Cardiology is much more than this.

An important issue which came up around 2014 was the exorbitant prices of stents for patients who needed an angioplasty. The number of such patients was around 500,000 per year with an annual increase of around 30 per cent.

The reason for the high prices was that there were several intermediaries in the stent supply chain between the manufacturer and the hospital authorities, especially in the privately owned ones. The average cost of an imported drug-eluting stent exceeded its real price by at least 60 per cent.

In the absence of any organised insurance system, most patients had to pay this money from their pockets in addition to the cost of the procedure.

This was taken up by a lawyer from Haryana, Birender Sangwan, whose friend had to pay Rs 126,000 for his father who underwent angioplasty in a Faridabad hospital. He filed a case in the Delhi high court to include heart stents in the National List of Essential Medicines in 2014. The court directed the government to get it included in the NELM.

It took three years and a number of contempt petitions by the lawyer before the government finally relented and handed over this pricing debate to the NELM. It worked and it was realised that the cost was being escalated several folds and left to the institutions at times and there was no maximum retail price written on the container boxes.

Finally, in February 2017, a price cap of approximately Rs 30,000 was mandated. It was a substantial reduction of at least Rs 90,000 for the imported drug-eluting stent for the patient needing it.

Many private hospitals seeing the loss in profits started hiking up the procedure costs and promoting reuse of the hardware during the procedure, a practice which is banned in Europe and the USA.

Such unhealthy practices need to be stopped by the hospitals and those found guilty need to be penalised.

Excerpted from When The Heart Speaks: Memoirs of a Cardiologist by Dr Upendra Kaul published by Konark Publishers Pvt Ltd, with the kind permission of the publishers.

Source: Read Full Article