National Award-winning filmmaker Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, who grew up in Delhi, on his memoir, what brought about his best-known work and why one has to be the change one wants to see.

When Arun Jaitley, then I&B minister, met Bombay filmmakers to discuss “censorship”, filmmaker Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra recalls having said, “take the scissors, throw it in the ocean.” “You need certification, not censorship. Mr Jaitley formed a committee (Benegal Committee, 2016) with chairman Shyam babu (Benegal), Kamal Haasan, Goutam Ghose, myself…we spent a year on it, spoke to all stakeholders, there was enough experience and representation in the room. We framed a law, he (the late Jaitley) liked it, but it never saw the light of day. The ministry changed and he (Jaitley) was made the defence minister,” says Mehra, 58, his long hair and beard freshly trimmed.

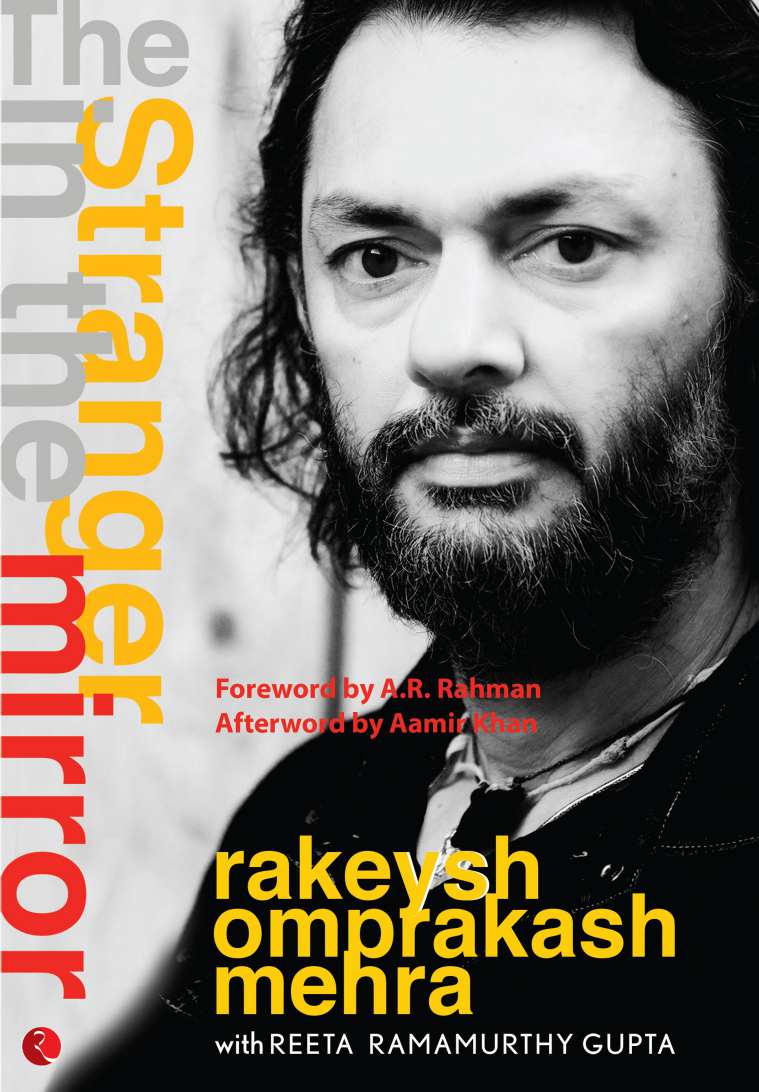

Such nuggets don’t find mention in his recently released autobiography, The Stranger in the Mirror (Rupa Publications, Rs 595), co-written with Reeta Ramamurthy Gupta, that has been four years in the making, with a working title “Interval”. One had to be “precise, not meander,” says Mehra, who starts his day by talking to himself — a stranger every time he looks into the mirror, a leitmotif that runs through his films, and, now, his memoir. The “avid reader of film books seldom found books on Indian films” and wrote one before his memory fades.

Mehra writes intimately of his successes and failures, his middle-class roots and aspirations to make it big. The second of three children, Mehra was born in the decade of counterculture and social revolution — the Sixties — in the syncretic Old Delhi. He grew up in the servant quarters of the very-British Claridges Hotel, where his father rose through the ranks from a dishwasher to food and beverage manager. It was there that, as a boy, he got a glimpse into the world of “goras” (foreigners), secretly watched his first cabaret show, and learnt to befriend water. Swimming (sports quota) landed him in Delhi University’s prestigious Shri Ram College of Commerce, but he fell short of qualifying for the final national team (water polo) in the 1982 Asian Games.

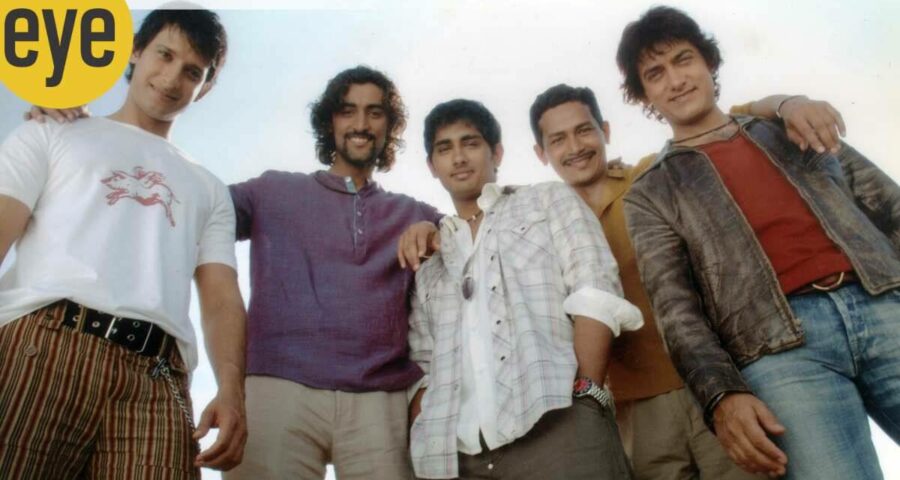

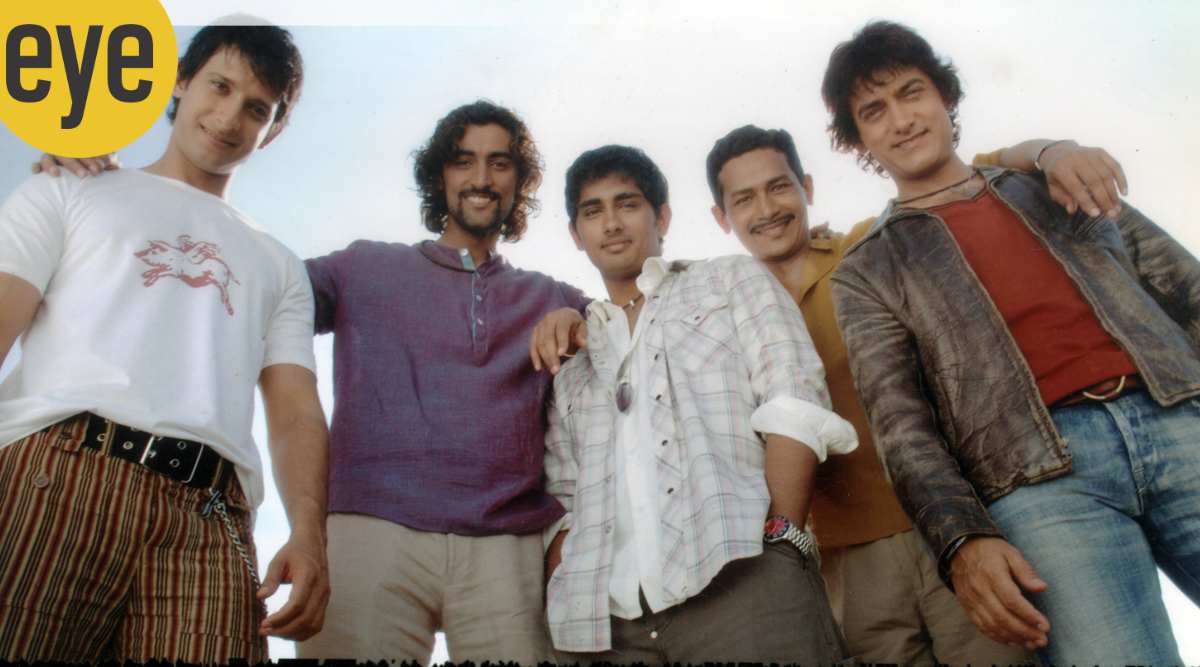

Films had always been a companion. If Mughal-e-Azam (1960) was the soundtrack of his childhood, his adolescence was spent watching movies gratis at Delhi’s single-screen theatres thanks to his father’s acquaintances from his ticket checker-torch man days at the now-defunct Jagat Cinema. It took 36 years — fabrics business, selling vacuum cleaners door to door, an advertising career (“over 200 ad film commercials”) — for filmmaking to embrace him. For his sophomore, Rang De Basanti (RDB, 2006), he wanted to turn the local sociopolitical context into world cinema, juxtaposing the past (freedom fighters Bhagat Singh, Shivaram Rajguru, Chandrashekhar Azad, Ashfaqulla Khan, Ram Prasad Bismil) with the contemporary. It became a milestone in Hindi cinema with its advocacy of citizens’ intervention for change. It also made Hindi-film dialogues great again.

Mehra quotes Sahir Ludhianvi’s poem, the inspiration for his first celluloid hit. “Bahut dinon se hai yeh mashgala siyasat ka, ki jab jawan ho bachche toh qatl ho jaye (For many days, it’s been the ploy of the establishment/to kill the young when they find their voice against the rulers)”. There were many triggers: the news about “flying coffins” (MiG-21s, called so because of their poor safety record); the VP Singh government’s introduction of the Mandal Commission in 1990 that brought the youth to the streets and saw a DU student Rajeev Goswami’s self-immolation bid in protest; and Mehra and friends who were fence-sitters in college would “point fingers at everything” but themselves. “That’s where RDB came from. I have a huge admiration for youngsters who join the idea of India — Army, Navy, Air Force, the IAS, IPS, IFS, politics, to bring about a healthy change,” he says.

The film, which had an “unpalatable military angle”, was shown to the IAF and Ministry of Defence. The then defence minister (Pranab Mukherjee) found no “problem” — unfazed by the film’s parallel that much of the blame falls on the shoulders of the defence minister — and the then Air Marshal found “nothing derogatory”. Were those different times? Mehra says, “I don’t see why you can’t make an RDB or Delhi-6 today. That’s a fallacy. To say the film is more relevant today is biased, unfair and against the present establishment…There will never be a perfect establishment. It wasn’t perfect when I was growing up. Right after the Emergency, I joined college. It was not good; it was not right. Likewise, the polarisation today is not good. A nation where everybody discusses politics on the breakfast table is not a healthy nation. The youngsters have to step up. The young energy is what brings the revolution. There can be various forms (of effecting change). There could even be a Tiananmen Square (protests in China, 1989), why not? It brought the most stringent power in the world to its knees — a lot started there.” In its afterlife, RDB roused people, bringing them to the streets to seek justice for model Jessica Lal’s murder in 1999.

In the memoir, Mehra’s first-person narrative is interspersed with voices from his personal and professional spaces, that give the readers a glimpse into his “easy-going”, “explorer” persona — and his eight-hour-long script narrations. It has interesting nuggets, too: when Daniel Craig auditioned for RDB but James Bond happened, AR Rahman replaced Mehra’s initial choice of Peter Gabriel for RDB’s music and Aamir Khan ensured Mehra pays double (Rs 8 crore) if he “defaulted” paying on time. Mehra is equally candid about his relationship with his film-editor-cum-wife PS Bharathi — the girl in a “polka-dotted skirt” he had met at adman Prahlad Kakkar’s office. “Marriages are outdated. We had to get married to fulfil social norms, otherwise society won’t let you coexist. We chose friendship 30 years ago, not a husband-wife relationship,” he says.

Mehra defies chronology to write first about his third film Delhi-6 (2009), starring Abhishek Bachchan. His first with him could have been Samjhauta Express, Bachchan maintained a diary and had become the character, but Jaya Bachchan announced her son’s debut would be JP Dutta’s Refugee (2000). Mehra, who burnt his script, says, “22 years ago, you couldn’t call a Pakistani Pakistani (but ‘padosi mulk’, neighbouring country), you couldn’t have your hero as a terrorist.” A decade later, the failure of the project closest to his heart, Delhi-6 — not a commercial success despite its popular music and relevant theme — would make Mehra sink into depression and turn to alcohol for solace for a very long time. Mehra admits that the criticism had hurt. “It was not the box-office debacle. It had a fair collection (Rs 52.18 crore), huge for us. You win some, you lose some, that’s the nature of the beast. If you can’t accept that, you’re living in a fool’s paradise. What threw me off was when the reason I was making Delhi-6 for didn’t get accepted,” he says. Mehra sent a fresh “Venice cut” to the Venice Film Festival that got lauded.

After the huge success of the sports biopic Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013), his projects have had lukewarm reception but he’s upbeat about OTT changing the game’s rules. Earlier, he couldn’t have dreamt of his film reaching a “theatre-less C-town in India” but Toofaan (2021, Prime Video) went to “200 countries, 86 million households at once,” says Mehra, who’s currently busy writing his take on — trying to reach the core of the thought of — the mythological drama Karna, in which Shahid Kapoor will play the lead role.

Does his mojo lie in making socially relevant films? “It’s not about the message. If that’s the intent, then it’s preaching, not telling a story. You want to feel about things strongly, but not all the time. If I were to make 10 films in my lifetime, five-six times I’d like to say what I feel. It could be a philosophy, like in Aks (2001), my first — I was trying to decipher about good and evil as being two sides of the same coin and treated it like a paranormal thriller. We give too much bhaav (importance) to filmmakers. Filmmaking has the impact, but it is not an agent of change. It can be the wire through which electricity passes, it’s not the electricity, that’s the audience — you, your consciousness,” he says.

Source: Read Full Article