The Chinese dependence is far from over, industry players are also citing a shortage of electronic toys in the country.

Until recently, Bengaluru-based Shumee Toys, which makes eco-friendly toys, Ahmedabad-based ARKidzoo Company, which focuses on flash cards and story books using augmented reality, and Pune-based Funvention that looks to raise interest of kids in studies through toys and puzzles were all little-known start-ups.

Earlier this year, however, Prime Minister Narendra Modi noted their names in his “Mann ki Baat” radio address that stressed his “vocal for local” campaign.

They were, he said, examples of the growing interest of start-ups and local manufacturers in the toy sector.

They are also among the major gainers of the government’s efforts to focus on the “toyconomy” to reduce “the 80 per cent dependence” on Chinese imports at that time.

The transformation has been remarkable.

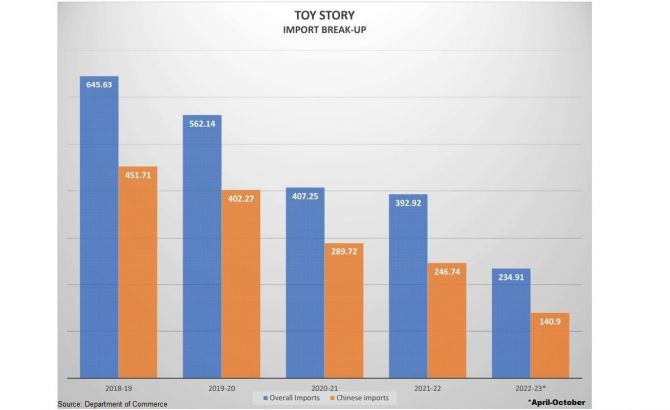

In the last four years (starting 2018-19), India’s imports of toys, games and sports requisites and their parts and accessories declined 39 per cent.

In the same period, Chinese imports, too, dipped 45 per cent from $451.71 million to $246.74 million in 2021-22.

More to the point, in the case of only toys, exports increased 61.38 per cent from $202 million in 2018-19 to $326 million in 2021-22.

Imports of toys alone have dropped 70 per cent from $371 million in 2018-19 to $110 million in 2021-22.

One of the major reasons for this import-export shift is a sharp increase in basic customs duty from 20 to 60 per cent in February 2020.

This was followed by the decision to bring toys under compulsory Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) certification starting January 1, 2021.

Under this, every toy manufactured or sold in India needs conform to the requirements of relevant Indian standards and bear the standard mark (ISO) under a licence.

This quality control became applicable to both domestic and overseas manufacturers.

These two decisions turned out to be the game-changer for the industry in terms of competing with Chinese imports.

According to the Toy Association of India (TAI), the size of the industry was around Rs 20,000 crore in retail value in 2020, of which only around Rs 5,000 crore came from local manufacturing.

Based on a report by IMARC, a market research company, the Indian toys market size reached $1.5 billion in 2022 and may touch $3 billion by 2028, a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.2 per cent.

“We are seeing a rise in our sales numbers.

“At present, we are exporting to around 30 countries and are planning to increase it to around 40 countries in the coming months,” said R Jeswant, chief executive officer of Chennai-based Funskool.

Funskool, a subsidiary of tyre major MRF, is part of the large organised section of the toy industry.

But now, industry sources indicate that with imports reducing, local manufacturing and the involvement of more micro entrepreneurs and start-ups is on the rise.

More than 100 new registered manufacturers entered the sector in the last two years and local production has gone up 20-30 per cent according to TAI.

BIS norms were introduced after a study by the Quality Council of India, an autonomous organisation under the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, in 2019 showed that out of 121 different varieties of toys procured only 33 per cent passed quality tests with 67 per cent failing to make the cut.

It cited that 30 per cent of plastic toys and 45 per cent soft toys failed to meet the safety standards of admissible levels of phthalates (a group of chemicals used to make plastics more durable) and heavy metals.

Industry experts indicate that the issue seems to be far from over because Chinese toys are still available in the Indian market and only around 1,000 local manufacturers have registered under BIS, despite widespread campaigning by the authorities.

On the other hand, there are only a handful of registered overseas manufacturers.

“Right now, there are too many Chinese toys in India despite BIS norms. Some are coming in the CKD (completely knocked down or delivered in parts and assembled at the destination) or SKD (semi-knocked down or partially-assembled) form,” said Ajay Aggarwal, TAI president.

Significantly, mass manufacturers are not prepared to come under the BIS umbrella owing to the level of paperwork this exercise entails and the heavy compliances burden it imposes.

One estimate says that the country has around 6,000 toy manufacturers, with a majority of them under the micro, small and medium enterprises segment.

In a sign that the Chinese dependence is far from over, industry players are also citing a shortage of electronic toys in the country.

“In India, the number of electronic manufacturers is relatively low.

“We are specially importing chips and ICs (integrated circuits) from countries like China, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

“We have suggested to the government that we can hire a company to make IC and chips for the local toy manufacturers and we can export also,” Aggarwal added.

Tellingly, despite the new-found focus in the sector, India still lacks a research and development (R&D) centre or a design institute to drive the changes in the sector.

Source: Read Full Article