As per the latest V-DEM report, in 2020, the third wave of autocratisation has accelerated considerably and now engulfs 25 countries and 34 per cent of the world population

Last month, V-Dem Project (Varieties of Democracy), a Sweden-based independent research institute, released its annual democracy report making a key observation that India, the world’s largest democracy, has turned into an ‘electoral autocracy’. As per the report, 87 countries are now electoral autocracies and home to 68 per cent of the global population.

Apart from this, the report also pointed to an accelerated autocratisation in several countries including G-20 nation-states United States, Brazil and Turkey that has hastened the decline of democracy globally. Liberal democracies, the report says, have diminished and now constitute only 14 per cent of people.

The report says that with the backsliding of democracy in Asia-Pacific region, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America, the level of democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen in 2020 is down to levels last found around 1990.

This decline in democracy, the report says, is part of the “third wave of autocratisation” – 25 countries, home to 34% of the world’s population (2.6 billion people), are in democratic decline by 2020. At the same time, the number of democratising countries have dropped by almost half down to 16 that are home to a mere 4 per cent of the global population.

What are the waves of democratisation?

The concept ‘Democracy Wave’ was first introduced by the American political scientist Samuel P Huntington in his book ‘The Third Wave’ in 1991. In the book, he writes that since the early nineteenth century, there have been three major surges of democracy as a political system and two brief periods of decline. He calls these surges as ‘waves of democracy’ and the ebbs as the ‘reverse waves.’

As per Huntington, the first ‘long’ wave of democratisation began in the 1820s, with the widening of the suffrage to a large proportion of the male population in the United States, and continued for almost a century until 1926, bringing into being some 29 democracies including France, Britain, Canada, Australia, Italy and Argentina.

He argues that this ‘long and slow wave’ was followed by a ‘reverse wave’ leading to the weakening of the democratisation process. Between Mussolini’s rise to power in 1922 and 1942, the number of democratic states in the world was brought down to a mere 12.

The triumph of the Allied Forces in World War II initiated a second wave of democratisation taking the number of democratic countries to 36 by 1962. This, says Huntington in the book, was followed by a second reverse wave (1960-1975) that brought the number of democracies back down to 30.

The third wave of democratisation, Huntington proposes, began with the Carnation revolution in Portugal in 1974 and continued with a number of democratic transitions in Latin America in the 1980s, Asia Pacific countries and, saliently, in Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union. He points out that this democratic wave was so strong in Latin America that out of 20 countries in the continent, only two countries (Cuba and Haiti) remained authoritarian by 1995.

In 1991, when he published the book, he observed that signs of the commencement of a third reverse wave were already there, with nascent democracies like Haiti, Sudan returning to authoritarianism.

What are waves of Autocratisation?

Following Huntington’s lead, a number of political scientists have used these concepts to explain the ebbs and flows in the march of democracy.

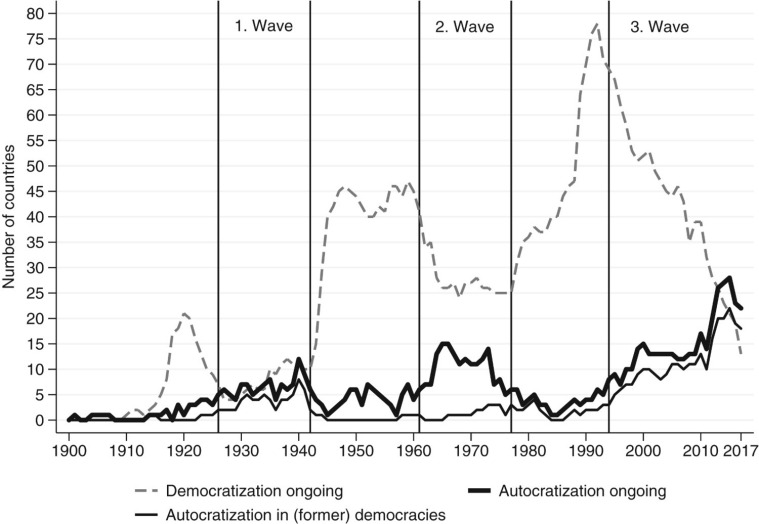

For example, in March 2019, Anna Lührmann and Staffan I. Lindberg published a research article, ‘A third wave of autocratisation is here: what is new about it?’ in which they mapped the strengthening and weakening of democracies across the globe in over a century and ‘identified’ a distinct third wave of autocratisation that commenced in 1994.

They used V-Dem’s data on 182 countries from 1900 to the end of 2017 (or 18,031 country-years ) to demonstrate a third wave of autocratisation. They did this by identifying a total of 217 ‘autocritisation episodes’ in 109 countries from 1900 to 2017.

The dates for the first two reverse waves presented by them are very similar to Huntington’s despite the conceptual and measurement differences. As per them, during the first reverse wave 1922–1942 a total of 32 autocratisation episodes took place; they identified 62 episodes in the second reverse wave between 1960–1975; during the ongoing ‘third wave’ of autocratisation they located 75 episodes starting from 1942 (until 2019).

“By 2017, the third wave of autocratisation dominated with the reversals outnumbering the countries making progress. This had not occurred since 1940,” they say in the paper.

“In sum, an important characteristic of the third wave of autocratisation is unprecedented: It mainly affects democracies – and not electoral autocracies as the earlier period – and this occurs while the global level of democracy is close to an all-time high. Hence, for now at least, the trend is manifest, but less dramatic than some claim,” they say.

Auotocratisation has become less dramatic

Political scientists like Micheal Coppedge note that a key contemporary pattern of autocratisation is the gradual concentration of power in the executive, apart from the more “classical” path of intensified repression.

Larry Diamond, another American political scientist sees the decade 2006 to 2016 as that of an incipient decline in democracy bringing in instability and stagnation among democracies. As per him, the decade brought an incremental decline of ‘grey-zone democracy’ (which defy easy classification as to whether or not they are democracies), deepened authoritarianism in the non-democracies, and caused decline in functioning and self-confidence of the established, rich democracies.

Although various observers including V-Dem, Freedom House, point to substantial autocratisation over the last decade in countries as diverse as the United States, India, Russia, Hungary, Turkey, and Venezuela, the democratic breakdowns have become less conspicuous. This, political scientists say, is because the contemporary autocrats have “mastered the art of subverting electoral standards without breaking their democratic façade completely.”

“Democratic breakdowns used to be rather sudden events – for instance, military coups – and relatively easy to identify empirically. Now, multi-party regimes slowly become less meaningful in practice making it increasingly difficult to pinpoint the end of democracy,” pinpoint Luhrmann and Lindberg in the article mentioned earlier.

“A gradual transition into electoral authoritarianism is more difficult to pinpoint than a clear violation of democratic standards, and provides fewer opportunities for domestic and international opposition. Electoral autocrats secure their competitive advantage through subtler tactics such as censoring and harassing the media, restricting civil society and political parties and undermining the autonomy of election management bodies. Aspiring autocrats learn from each other and are seemingly borrowing tactics perceived to be less risky than abolishing multi-party elections altogether,” they argue.

As per Luhrmann and Lindberg, the ‘erosion model’ has emerged as the prominent tactic in the third wave of autocratisation. The first and second waves, on the other hand, were dominated by blatant methods such as military coups, foreign invasions or abolishment of the key democratic institutions by a legally elected officer.

“Democratic erosion became the modal tactic during the third wave of autocratisation. Here, incumbents legally access power and then gradually, but substantially, undermine democratic norms without abolishing key democratic institutions. Such processes account for 70 per cent in the third reversal wave with prominent cases of such gradual deterioration in Hungary and Poland. Aspiring autocrats have clearly found a new set of tools to stay in power, and that news has spread,” write Luhrmann and Lindberg.

The ‘Third Wave’ accelerates

As per the latest V-DEM report, in 2020, the third wave of autocratisation has accelerated considerably. “…It now engulfs 25 countries and 34 per cent of the world population (2.6 billion). Over the last ten years the number of democratizing countries dropped by almost half to 16, hosting a mere 4 per cent of the global population,” says the report.

The Third Wave by Samuel P Huntington

A third wave of autocratization is here: what is new about it? by Anna Lührmann & Staffan I. Lindberg

Eroding Regimes: What, Where, and When? by Micheal Coppedge

Facing up to the democratic recession by Larry Diamond

Source: Read Full Article