‘Indira Gandhi, it appears, did not to consult her Cabinet colleagues, or the diplomats, or the civil servants when she decided to sign the agreement at Shimla.’

‘We ruefully recall Bhutto’s perfidy and the Indian prime minister’s gullibility,’ says Lieutenant General Ashok Joshi (retd).

The blitzkrieg by India that brought about the spectacular victory on December 16, 1971 was a rare event in post-Independence history.

The military campaign that had lasted no more than 14 days produced decisive results on the battlefield. Such was the impact of the speed of operations that a stunned Pakistani military leadership surrendered to the numerically smaller Indian contingents at Dhaka.

The surrender ceremony, which included a guard of honour to the winning commander, was promptly organised by the Pakistan military. Over 90,000 Pakistan prisoners of war were in the bag.

The Indian military operations liberated the eastern wing of Pakistan from the brutal repression by the Pakistan army and assisted Bangladesh in securing its freedom. The prestige of the Pakistan military was in the dumps.

The undertaking of a military campaign by India to liberate the oppressed and persecuted Bengalis in the eastern wing of Pakistan had not been a facile decision on its part.

The refugees started trickling into India from East Pakistan towards the end of March 1971. Soon, the trickle turned into raging torrents of hundreds of thousands, and eventually of millions. Several hundred thousand Bengalis had been massacred by the Pakistan army. No wonder that the dispossessed and the hunted turned to India for succor.

Finding food, shelter and minimal medical help for this sea of humanity was a herculean task for India, itself a developing nation. But it shared with the refugees the half loaf that it had.

The United States, normally at the forefront of humanitarian causes, was preoccupied at the moment with building a friendly relationship with the People’s Republic of China. The move was based on enduring geopolitical factors that would confer major advantage on the US in the ongoing Cold War.

The initiative had come at the highest level and President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had decided to open this new front in the Cold War with Pakistan’s assistance. This would have outflanked the Soviet Union.

The Pakistan military was active in helping the US establish a friendly relationship with China. Such was the obsession of the Nixon-Kissinger duo with their new Cold War manoeuvre that they had become unmindful of public opinion in the US. Their obligation to the Pakistan military made them turn a blind eye to the reign of terror unleashed by the Pakistan army.

Many eyewitness accounts of Pakistan atrocities in the eastern wing appeared in the US media. The Blood Telegram tells the story of the duo’s insensitivity in vivid detail. The US exerted considerable pressure on Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to desist from any military action against Pakistan.

Indira Gandhi showed great fortitude and courage in withstanding this pressure. She entered into a treaty of friendship and cooperation with the Soviet Union in August 1971 and turned the tables on Pakistan.

Her foresight paid rich dividends, and when the US sent the USS Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal with a view to browbeating India, Soviet submarines nullified the effect by trailing the task force. The Indian military’s swift and decisive operations left the US with no choice.

The happy enmeshing of military and political objectives by India continued. It was a wise decision to commence the deinduction of the Indian armed forces from Bangladesh as early as March 2, 1972. This harmonised the national interests of India and Bangladesh.

The pursuit of political objectives by India after the military victory was not so sure footed. The Indian military had created a unique opportunity that was waiting to be exploited.

The victory against Pakistan had been won at considerable human cost — over 3,840 soldiers killed and about 2,500 wounded. The sad truth is that India failed to make use of the unique opportunity that was ripe for exploitation.

The very large number of Pakistan POWs in Indian custody yielded a great leverage to India and it would have been unwise not to utilise it in the national interest. It is true that India could not have retained the Pakistan prisoners indefinitely; it did not have to.

Some of the leverage could have been used up to get back Indians captured by Pakistan. This aspect had obviously not been well thought out and there are reports even now that 54 Indian military men were left to rot in Pakistan jails.

India had the choice of appointing a judicial commission with members from India and Bangladesh to record evidence to expose the role of senior Pakistan military officers in atrocities committed against the Bengalis.

The guilty, mostly senior Pakistan army officers, could have been retained. India could have released a large majority of POWs.

The genocide in Bangladesh was the handiwork of the Pakistan generals who were racists to the core. They were waiting for an opportunity to sort out the contentious Bengalis who had the temerity to ask for greater share of power and resources.

They had no time for the ‘small and dark’ people from the eastern wing, particularly so if they were Hindus. The Pakistan generals decided to teach a lesson to the unruly in the east, and eliminate the Hindus. These aspects of the stark reality could have been culled from the available evidence which was waiting to be formally brought on record.

This was a unique opportunity for India to place before the common man in the subcontinent, the problems created by the Pakistan military leadership for the entire subcontinent, not excluding their own country.

Unlike in most other countries where the armed forces are raised and maintained for protecting national interests and assets, the Pakistan military had appropriated a country for itself.

It ruled out the possibility of peaceful coexistence with India, and created a myth that hostility to India was a pre-condition for the very survival of Pakistan.

Next, it tried to appropriate the leadership of the Islamic world by pretending that it is an extension of the Middle East into the subcontinent. Thus, it justified a fat military budget to an impoverished country.

This was also an opportunity for India to persuade Pakistan to accept the ceasefire line (CFL) in Jammu and Kashmir as the de facto international border. The Pakistan military has looked upon the CFL as eminently violable. Most of the wars between the countries can be traced to this conviction.

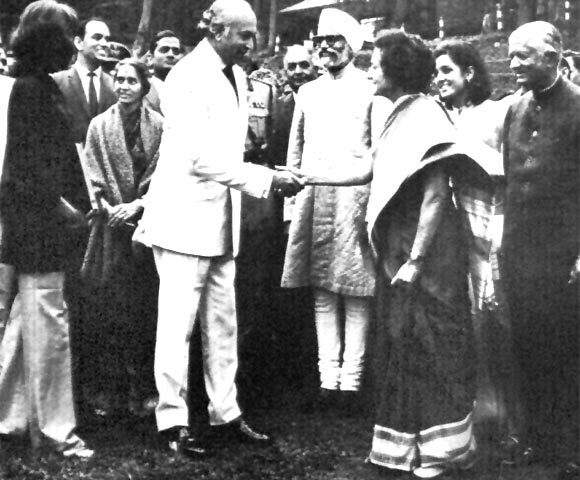

Six months were to lapse before the talks to normalise the relationship between the two countries were held at Shimla in July 1972. The Pakistan objective was clear and simple — to take back the prisoners.

India had been informed that Bhutto had vowed to sleep on the ground for so long as the Pakistan prisoners were in Indian custody. This dramatic gesture was principally aimed at the home constituency.

The agreement that was on the anvil at Shimla reflected the fulfillment of all the requirements of Pakistan that Bhutto had brought with him. There was nothing in it for India except Pakistan promises of goodwill and good neighbourliness.

It offered to allow India and Pakistan to retain the territory across the CFL that they had captured in December 1971. This conferred no advantage on either side.

On the other hand, Pakistan was to get back all the prisoners without any enforceable commitment on its part. Bhutto was unwilling to include in the agreement the one single Indian demand that the de facto CFL would be recognised by both countries as the international border.

There were some internal contradictions too in the draft agreement as it was; What it said in the preamble that ‘the two countries (would) put an end to the conflict and confrontation that have hitherto marred their relations’ was negated in Paragraph 3 (ii) by saying that the agreement about the withdrawal of the troops across the new ceasefire line would be ‘without prejudice to the recognized position of either side.’

This created room for Pakistan to air its unchanging argument that the Kashmir dispute was to be resolved by plebiscite, and further that Kashmir was a part of the unfinished agenda of Partition.

This being the case, Indira Gandhi was not willing to sign the agreement. The Shimla talks had virtually broken down. This meant that Bhutto would have had to return empty handed, without securing any agreement about the repatriation of Pakistan prisoners.

At this stage, Bhutto pleaded with the prime minister that he needed time to prepare Pakistan for acceptance of the CFL as the de facto international border although he himself had no reservations on that score.

In order to achieve the common purpose, India should help Bhutto in building up his image in Pakistan. To this common end, he requested Indira Gandhi to sign the agreement although the written word was at variance with his verbal assurance.

‘Aap mujh pe bharosa ki jiye (Trust me)‘ and Indira Gandhi believed him. She decided to sign the agreement. This decision was taken at the eleventh hour when the talks had broken down and the bags had been packed.

In the early hours of the morning, some unpacking had to be done to get the agreement ready for signatures because by then even the typewriters and stamps had been packed. It is believed that in spite of much searching the stamp could not be found, and the agreement does not bear the stamp impression.

Bhutto had his way and except for a promise he conceded nothing.

India lost opportunities by signing the Shimla Agreement on July 2, 1972. On that day, India agreed to repatriate Pakistan POWs without any pre-condition or any written assurance from Pakistan.

It is believed by some that the release of Pakistan prisoners was agreed to in return for the recognition of Bangladesh by Pakistan. If so, there is no such mention in the agreement. The recognition ultimately came about in 1974.

The linkage between the release of prisoners and the recognition of Bangladesh by Pakistan is a highly tenuous proposition.

The prime minister, it appears, did not consult her Cabinet colleagues or the diplomats or the civil servants when she decided to sign the agreement at Shimla.

The question of consulting the military leadership just did not arise. General (later Field Marshal) Sam Manekshaw, the army chief, had certainly not been consulted. There may have been a reason for it.

After the victory at Dhaka, his image had been built up by the media in the popular mind. This was clearly not acceptable to the political leadership or the bureaucracy. Possibly Bangladesh should also have been consulted before releasing the prisoners since the Mukti Bahini had played its part in bringing the Pakistan army to its knees.

Bhutto returned victorious. He set about training terrorists to operate in India and building Pakistan’s nuclear bomb.

Very little that is tangible is left of the talks at Shimla.

We ruefully recall Bhutto’s perfidy and the Indian prime minister’s gullibility.

It now seems that what was won at Dhaka was squandered away in Shimla.

Source: Read Full Article