‘Some of his decisions were not so good, but his intentions were always guided by a deep national interest.’

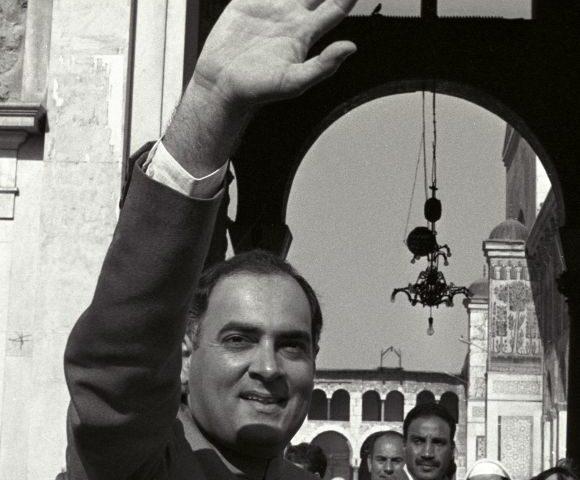

May 21, 2021, marks the 30th death anniversary of Rajiv Gandhi, who was assassinated on this day in 1991 by Sri Lankan Tamil terrorists in Sriperumbudur, Tamil Nadu, while on an election campaign.

Elected prime minister in 1984 with the biggest parliamentary majority ever, Gandhi oversaw many historic developments. Peace in terror-hit Punjab was restored through an accord, as also in Assam and Mizoram.

He also had a vision for the country’s technological future, and laid the foundations for the telecom boom that was to follow.

Indeed, the seeds for India’s emergence as an economic and military superpower were sown in his tenure.

But as always, there were also negatives to his governance.

The anti-Sikh riots in Delhi and elsewhere that followed his mother Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination, opening up the locks of the Babri Masjid and thus breathing life into an issue that had lain dormant for decades, overturning a Supreme Court verdict in the Shah Bano maintenance case to please the Muslim orthodoxy, the Indian Peace Keeping Force fiasco in Sri Lanka, and finally the Bofors kickbacks scandal which saw him voted out of power in 1989 — it is hard to balance the positives and negatives of his rule.

Three decades after his death, when his party is at its parliamentary nadir and when rivals harp on ‘dynastic politics’ within the party, how should we see Rajiv Gandhi’s legacy? As a man who saw tomorrow, or as someone who promised much only to deceive?

Rediff.com‘s Syed Firdaus Ashraf spoke to veteran Congress watcher Rasheed Kidwai, a Visiting Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation and the author of two books on the Congress party, about the Rajiv years, their impact on the country and in what lessons they hold for today.

How do you assess Rajiv Gandhi’s legacy 30 years after his passing?

Rajiv Gandhi’s legacy was quite inspirational, his tenure was full of momentous decisions. He had started off very well, but two years after becoming the prime minister, Rajiv had became peevish and cynical.

Just as Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi had diminished with advancing years, it happened to Rajiv a bit too soon. Between 1987-1989, many allegations of kickbacks and scandals eroded his credibility.

So, it was a mixed bag. Some of his decisions were not so good, but his intentions were always guided by a deep national interest.

That is the reason why he is appreciated and we are still remembering him.

Remember, when he died he was very young.

He was 1944 born and died in 1991.

He was the youngest prime minister India has ever had.

He was only 40 when he became prime minister of India.

He had a rollercoaster ride.

Rajiv Gandhi’s biggest contribution and legacy, which is sort of under-recognised, is that he put a thrust on technology, science and scientific temper.

He launched missions, be it technology, water, environment, climate change and global peace.

Many of these measures are under-recognised today.

Look at the telecom sector, Rajiv Gandhi was the architect of the information technology and telecom reforms which he set up with his friend Sam Pitroda.

I think he set up five technology missions which grew over the years.

Therefore, today we have the cheapest telephony or Internet rates in the world.

It is generally believed that India is suffering today because of his decisions on Kashmir, or the genocide of Sikhs in Delhi, or even the Ram Mandir issue. Should he not be held responsible for these?

It is a very uncharitable view to look at Rajiv Gandhi’s legacy in that light.

He inherited the Kashmir and Punjab problems which date back to Partition.

I do not want to go into great details, but that is a fact.

He was very sincere in solving problems.

Rajiv Gandhi was one prime minister who sacrificed his successive elected state governments.

Look at the Assam Accord, for example when he handed over power to the Asom Gana Parishad in December 1985.

The AGP’s victory made Assam the fifth state to be ruled by a regional party and the eighth to be lost by the Rajiv-led Congress.

In 1986, Laldenga was brought from Britain and made chief minister of Mizoram, which was given full statehood the following year. It had earlier been a Union territory after being carved out of Assam in 1972.

The year 1986 also saw Rajiv sign an accord with Farooq Abdullah in Kashmir, leading to the exit of the key Congress leader in the Valley, Mufti Mohammad Saeed, from the party.

In Punjab, Darbara Singh, the secular and balanced chief minister of Punjab, had in 1983 been sacked by his political master, then prime minister Indira Gandhi. Rajiv held state polls in September 1985 that saw the formation of the Akali Dal government.

Looking back, Rajiv’s gambles to forgo power did not make many of these accords stable, though his moves were based upon realism and aimed at quelling unrest.

By the time Rajiv was voted out of power in 1989, India’s moral and administrative fabric had been corrupted to the core.

The decline had begun during Indira’s tenure and the Emergency, but, by 1989, respect for law, human dignity and the rights of an individual were not even talking points in the country’s administrative culture.

This track record, no prime minister of India can match.

Today, if you see, majorities are being engineered in border-sensitive states of the north east.

Rajiv was straight-forward and clean at heart.

It is said that he was responsible for opening up the locks of the Babri Masjid.

But a recent book by Wajahat Habibullah says that Rajiv Gandhi was not in the know.

It was Arun Nehru who as minister of home told then Uttar Pradesh chief minister Vir Bahadur Singh, that Rajiv Gandhi wanted the locks of the Babri Masjid to be opened.

That led to the entire problem.

Of course, Rajiv did make certain mistakes, like sending the Indian Peace Keeping Force to Sri Lanka.

That was a major misadventure from his side.

We must realise, though, that whoever had advised Rajiv Gandhi, it was a great misadventure.

Remember today, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s minister, Hardeep Puri, was the number two diplomat (in Sri Lanka) when the IPKF was sent.

Why has nobody probed what were the inputs of the Indian high commissioner and that of the deputy high commissioner to the Rajiv Gandhi government at that point of time?

When you look back and see how he overturned a Supreme Court judgment and restored the Muslim Personal Law in the Shah Bano case, don’t you feel he had started this whole Muslim appeasement politics?

About the Shah Bano case we have to remember that the Muslim clergy and Muslim masses then did not want this new law and wanted to continue with the old existing Mohammedan law on divorce of Muslim women and maintenance settlement.

But what have successive governments learnt from it?

If the majority wants something, we see so many governments’ legislations and decisions determined by this consideration of the majority.

Has any lessons been learned?

The answer is, No.

Of course, Rajiv Gandhi is to be blamed for the Shah Bano fiasco, but as successive books show, who were the people to be blamed? They were Zia-ur Rahman Ansari, M J Akbar and Najma Heptullah.

Both Akbar and Heptullah are in the Bharatiya Janata Party now.

These people who were actually responsible for it were rewarded, and it is a paradox.

Does it mean Rajiv Gandhi was, as we say in Hindi, kacche kaan ke (wet behind the ears) and could be easily manipulated into doing things?

Let me pose a counter. Do we assume that that the present COVID-19 crisis, of shortages of oxygen and beds, are a failure of the system and not that of Prime Minister Modi?

Then, by the same yardstick, Rajiv Gandhi’s mistakes — be it the Indian Peace Keeping Force or Ayodhya or Shah Bano — were a systemic failure as he was given inputs by his advisors, foreign office and other institutions.

We must remember Rajiv Gandhi was an Indian Airlines pilot.

He was an accidental prime minister.

He came into politics after his brother Sanjay died (in a plane crash). He had no prior ministerial experience or interest in politics.

Let me quote some books to substantiate what I am saying.

When (Sanjay Gandhi’s friend from Doon School) Akbar ‘Dumpy’ Ahmed suggested Rajiv’s name from Amethi after Sanjay’s death, S S Gill quoted Indira as saying, ‘Do not be silly. His [Rajiv] politics is not like ours.’ [page 392, The Dynasty — A Political Biography of the Premier Ruling Family of Modern India, S S Gill, HarperCollins 1996].

Indira’s friend Pupul Jayakar has written about how Indira told her that Sanjay was very frugal, but Rajiv and his wife ‘need certain comforts’. [page 417, Indira Gandhi — A Biography, Pupul Jayakar, Viking 1988]

He wanted to reform the Congress party.

He wanted to modernise the Indian nation, wanted economic reforms and economic restructuring which were later followed by P V Narasimha Rao and Dr Manmohan Singh of which we reaped the fruits of benefit.

So, I think to blame Rajiv completely is wrong and to absolve him completely is also wrong. The truth lies somewhere in between.

The Bofors kickbacks scandal was the biggest bolt to him.

It was a big blow to him and the Congress party.

The party did not recover in 1989 and subsequently also.

Again, nothing has been proved and Rajiv Gandhi was absolved by the Delhi high court and other courts.

It is a very telling commentary on the kind of legal system we have.

People are accused of corruption and not convicted by a court of law, and by that yardstick are innocent.

But what happens to the period when the case is going on?

Take the example of Abdul Rehman Antulay, then Maharashtra chief minister who was accused of corruption.

After 20 years he was declared innocent, not guilty.

But, then, for 20 years he lived in the wilderness, and who is going to be held accountable for that period?

He could have grown in national stature as a politician, but instead lived in anonymity and insult.

In the 1987 Allahabad by-elections and 1989 general elections, V P Singh used to say that he had the proof and names of beneficiaries of Bofors kickbacks in his pocket.

But he never disclosed it.

After that the Chandra Shekhar government came and even the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government ruled for six years, but nothing came out of the Bofors case.

What about Rajiv Gandhi’s foreign policy, was it also a mixed bag?

Rajiv Gandhi had a vision and deep understanding of foreign policy issues.

He must have inherited it from his grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru or mother Indira Gandhi.

He had a very good set of advisors advising him: K Natwar Singh, G Parthasathy, Mani Shankar Aiyar, S K Singh and K R Narayanan who spent their lifetime in foreign policy. They were towering personalities.

Rajiv had a very open mind on many critical and vexed issues.

When he went to China, he went with a very open mind of give and take. Therefore, his trip to China was very successful.

Even with Pakistan, he had a formidable challenge in Zia-ul Haq who was a very crafty politician and dictator, but Rajiv Gandhi wanted good relations with Pakistan.

He went for the campaign of disarmament and call for a nuclear-free world.

Rajiv Gandhi at that point of time was a major global player.

He was not a weak person and understood India’s foreign policy requirements.

His foreign policy was pretty good, and he is not given the credit which is due to him.

You mentioned Pakistan, but there are allegations that Rajiv rigged the 1987 assembly election in Jammu and Kashmir to ensure Farooq Abdullah’s victory after which many young Kashmiris took to arms as they felt India would never hold free elections in J-K.

In principle, every decision or any lapse or failure should fall at the doorstep of the political leadership, that is the prime minister, and at that time it was Rajiv Gandhi.

We must keep that in mind and we must consider that for present-day India too.

The key point here is, Rajiv Gandhi’s Kashmir policy was guided by the then governor of J-K, Jagmohan, who held the post even during V P Singh’s time.

He evicted Kashmiri Pandits from the Kashmir valley and from that point of time Kashmir politics, which was not communalised and polarised, became communal and polarised.

Rajiv’s attempts to build bridges with Zia-ul Haq and Benazir Bhutto were sincere.

Even though he won 190-plus seats in the 1989 Lok Sabha election and the Congress the single largest party, why did he not form the government with an alliance?

Among other qualities Rajiv Gandhi had was he was a democrat at heart.

He understood the Westminster model of parliamentary democracy.

He knew that if an incumbent prime minister does not get a majority, he should not form the government.

That was the yardstick that he kept in mind.

From 1996 to 2004 that changed.

Rajiv put up a very shining example.

He could have cobbled up a majority and formed the government in 1989, but did not do so.

He declined. He allowed others to form the government.

It was V P Singh who formed the government with the Hindu right and the Left’s support.

The country paid a price for the V P Singh and Chandra Shekhar governments and ultimately Rajiv Gandhi paid for it by sacrificing his own life.

But it was Rajiv Gandhi who withdrew support to the Chandra Shekhar government in 1991.

It was a very unprincipled form of an alliance government.

The Chandra Shekhar government had only 54 MPs and the rest 400 MPs supporting it were out of the government.

This was something Rajiv Gandhi was waiting for and there was nothing unethical about it per se.

The same thing was done by Indira Gandhi after she allowed a split in the Janata Party and supported the Charan Singh government.

Charan Singh was prime minister for a very short tenure and Indira Gandhi withdrew her support only to bounce back in 1980 to win the elections and become prime minister again.

Rajiv Gandhi was just following his mother’s footsteps.

Chandra Shekhar knew that he was at the mercy of the Congress party as his party did not have a majority of its own.

Moreover, Rajiv Gandhi and Chandra Shekhar lacked personal rapport.

The rapport was between Chandra Shekhar’s minister, Subramanian Swamy, and Rajiv Gandhi.

Swamy even claimed that Rajiv wanted him to be prime minister, but I don’t know whether it is true or not.

The fact of the matter is there was total distrust between Rajiv Gandhi and Chandra Shekhar. That resulted in a breach of faith.

He was not morally, constitutionally or duty bound to support the Chandra Shekhar government for five years.

One can always question why did he withdraw support after just four months.

Because Rajiv Gandhi felt that he could win the elections in 1991 if they were held.

That is what happened as the Congress got 231 seats in 1991, but Rajiv Gandhi himself was assassinated.

Rajiv Gandhi is blamed for the Sikh genocide in Delhi of 1984 just as Narendra Modi is blamed for the 2002 post-Godhra riots.

1984 was a very traumatic period for the country.

The Bhopal gas tragedy happened.

There was lack of accountability.

Warren Andersen, CEO of Union Carbide, got away and the gas victims did not get adequate compensation.

The Sikh genocide was a shame and I think the society collectively was responsible.

Rajiv Gandhi was a young prime minister then.

But didn’t he say, ‘Ek bada ped girta hai toh dharti hilti hai (the ground shakes when a giant tree falls)’ to justify the anti-Sikh violence?

I am glad you asked this question.

We must have a sense of dates.

Today, the Internet is there and you can do a search as to when Rajiv Gandhi uttered these words.

It was in the third week of November 1984.

The genocide took place on October 31 and in the first week of November 1984.

This remark by Rajiv Gandhi was atrocious, but it was made much after all had happened.

The Sikh genocide was a savage reaction from members across societal strata and economic groups who participated and went barbaric.

I was present in Delhi then and saw it in the first person.

Responsible citizens were acting in a beastly manner.

I don’t want to go into details because Dr Manmohan Singh has spoken about this issue.

Of course, Rajiv Gandhi was responsible for not controlling the genocide, but P V Narasimha Rao, the then home minister, and the lieutenant general of Delhi (P G Gavai) too did not do anything to stop the genocide.

The Sikh genocide was a blot on Rajiv Gandhi and it always kept bothering Sonia Gandhi, who was apolitical at that time.

As the Congress party historian, one of the reasons I believe she made Dr Manmohan Singh the prime minister in 2004 was she wanted to atone for the wrongs which the Congress party and her husband did in 1984.

Rajiv Gandhi came to power with a huge majority of 400-plus seats, something even his grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru never got, yet in three years he became unpopular and lost the confidence of the people.

Why do you think Narendra Modi never lost that sheen in his first tenure? How did he keep going?

I have written a book for Rajkamal Publications which will soon be published.

It is called Bharat ke Pradhanmantri (India’s prime ministers) where I have examined the tenure of 14 Indian prime ministers.

I think Rajiv Gandhi was very young, naïve and lacked the kind of political craftiness which other prime ministers had, like Narasimha Rao, Vajpayee and Modi.

He lacked political management skills.

His sort of durbar was a mix of people who worked at cross-purposes.

Therefore, there was not a single reference point or set of advisors.

Modi, on the other hand, has been good at handling crises and averting them as the chief minister of Gujarat and had experience in running a state.

Rajiv Gandhi lacked an element of drama in his rule and event management.

Some glimpses were shown by V P Singh, though, who was his successor.

Source: Read Full Article