‘From the very start, PM Modi was insistent that visiting foreign leaders should be exposed to an India beyond its capital.’

‘Through these experiences, he felt that the full Indian narrative would be much better understood across the world,’ explains External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar.

A riveting excerpt from Bluekraft Digital Foundation’s Modi@20: Dreams Meet Delivery.

As he took over as Prime Minister on 26 May, 2014, Narendra Modi surprised India’s foreign policy establishment by making a bold move in that domain.

He invited neighbouring leaders to the swearing-in ceremony of his Council of Ministers in New Delhi.

This unusual decision, leave alone the enthusiastic response, was not even contemplated by most observers.

There was even more surprise that this initiative should come from someone who many thought of as a novice in international relations.

Over the next few years, the world was to discover that he was, in fact, a leader who had developed his policy insights and ideas over many years.

Not just that, he also had his unique way of messaging, implementation and follow-up.

Since then, we have all become a little more familiar with the strategy and approach of Narendra Modi.

Only the very partisan would dispute that their cumulative impact has significantly enhanced India’s global stature.

It is, therefore, worth reflecting on the habits and worldview of a Prime Minister who has put such a strong personal imprint on foreign policy.

Along with his legendary energy level, what is striking about Narendra Modi is his enormous curiosity about the world.

His zest to absorb and process information is matched only by the ability to deploy it effectively.

For us, it may be a data point; for him, it is a way of connecting and influencing.

This may be an innate trait of a politician, but he has taken it to an altogether different level.

The goal is obviously to arrive at the best possible understanding of what awaits him and to shape it to advantage.

It could be the intricacies of American politics before meeting President Obama, Chinese history as he was going to Xian, or perhaps the post-Soviet era to get a good feel for President Putin.

He would not only soak in what was being explained but constantly push us to do better.

The interest may pertain to happenings, subjects and domains; it could as easily be about people and their interplay.

There is also a sense of self-discipline in the exercise.

He wants to be clear about the red lines before engaging.

For the PM himself, sources of information are broad and diverse, ranging from the spoken and written word to the officialdom, political world, media or networking.

The idea is to get into the mind of the other party.

Interacting with him as Foreign Secretary, I noted that he was never hesitant to ask and always patient in listening.

What has now become an SOP (standard operating procedure) for the Delhi bureaucracy was initially a novel experience for all of us.

Anyone engaging with him at any level clearly had to prepare thoroughly to hold their own.

A clinical analysis of a period that I know well brings out how much the Prime Minister has shaped its contours.

But the experience of participating in policymaking has also been a process of discovery about him.

There are clearly learnings and judgments that Narendra Modi brings to bear from his chief ministership days.

His extensive travels within India and around the world in the period before joining the government have given him a good feel for social forces and political sensitivities.

I had anticipated some of that but was still sometimes taken aback at the highly-informed references he would make to countries and persons in our conversations.

During his 2014 visit to the US, while discussing the instincts of Americans, I spoke of travelling across that country in my younger days, only to discover that he had been to more states than me.

And as he jokingly told me, not by car or air but on a Greyhound bus! Similarly, his long-standing acquaintances in Diaspora societies suggest an early interest in foreign affairs.

It could be Mauritius, Guyana or Suriname; he seemed to know so many people.

His sojourns in Nepal were similarly a revelation, be it insights or factoids about that society.

For someone schooled in orthodox diplomacy, it dawned on me that he had approached the same landscape from a more socio-political and grounded perspective.

It is said that travel broadens the mind and certainly in his case, it appears an important contribution to PM’s global awareness.

This is because he is autodidactic by nature with a perpetual desire to comprehend the world better.

That PM Modi has little appetite for conventional sightseeing is well known.

What I discovered accompanying him was how strongly the experiences abroad were driven by a goal of identifying and absorbing best practices.

The railway station we went to in Berlin fed into his modernization plans at home.

The bullet train in Japan actually ended up as a project.

The convention centres where we spent time, each of them had a lesson to offer as we went about building our own.

A cleaned up river in Seoul further strengthened our resolve on rejuvenating the Ganga.

The public housing in Singapore was an input into our affordable housing scheme.

As a student of history, the Prime Minister reminded me of the Meiji era reformers in Japan who contemplated the world through the lens of changes at home.

One of the shifts that PM Modi brought into Indian foreign policy is its focus on leveraging external relationships for domestic development.

After all, the Asian economies that developed rapidly in the era of globalization were those that had accorded precisely this primacy to economic growth.

This, of course, was a far cry from the earlier days of ideological hubris and looking down on business.

But to understand this facet of Prime Minister Modi, it is necessary to go back to Chief Minister Modi.

By initiating the Vibrant Gujarat Global Summits, he created a platform to encourage flow of resources, technology and best practices.

Visits and interactions that were at its core were clearly an invaluable experience for him.

Whether it was partners like Japan, Canada, Denmark, South Korea or Kenya, or sectors like automobiles, railways, pharmaceuticals, renewables and chemicals, they demonstrated that the world would respond to right policies.

Interestingly, many of the relationships formed in this period helped to give a head start as new directions were set in his prime ministership.

His conviction that India must grow with the world would constantly lead him to advise his Cabinet colleagues to be connected and open-minded.

The practice of global personalities, starting with Singapore Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam, delivering the NITI Lectures to policymakers is very much in that vein.

The Vibrant Gujarat gathering of entrepreneurs and investors certainly helped to make Gujarat think internationally.

There were not many other events in the country that could be put in the same class.

Pulling off this achievement regularly clearly infused confidence in the ability to think bigger.

This ambition kicked in strongly once Prime Minister Modi raised his global profile after assuming office.

In the years that followed, India’s engagement with the world reflected the vision that he had for his nation.

India had done two collective summits till then with Africa; the third one, held in 2015 under the vision of PM Modi was of a different order with forty-one leaders present from that continent.

Before 2014, the country had invited individual ASEAN heads for the Republic Day; the celebrations held in 2018 saw all ten ASEAN heads of State attending.

Meetings with the European Union had taken place before; the 2021 engagement involved all twenty-seven EU leaders for the first time.

Whether it was the Nordic States, Central Asia or the Pacific Islands, the collective engagement carried its own message.

This was a Prime Minister who, by the dint of his earlier experience, has made the country think ‘scale’ in a range of domains.

There are other examples of the influence of the Gujarat period on Modi’s prime ministership.

As a Chief Minister, he was an enthusiastic proponent of renewable energy well before this became mainstream thinking.

His experiments with solar panels on canals also attracted international attention.

Tellingly, he authored a book called Convenient Action in response to the perception of climate change being an inconvenient truth.

And being Modi, he also established a department within the state government on climate change as far back as 2009.

If we fast-forward to COP-21 in Paris, it is no accident that he was now a prime mover to establish the International Solar Alliance.

Similarly, his state-level experience on disaster recovery led him to propose another global initiative: the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure.

It was revealing that global issues that he took up as PM — especially terrorism, climate change or disasters — were confronted squarely by Chief Minister Modi during his terms in office.

The long stint heading the state also gave his foreign policy thinking a greater federal perspective.

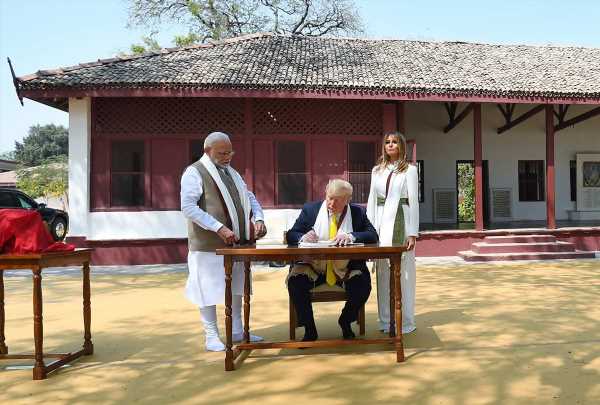

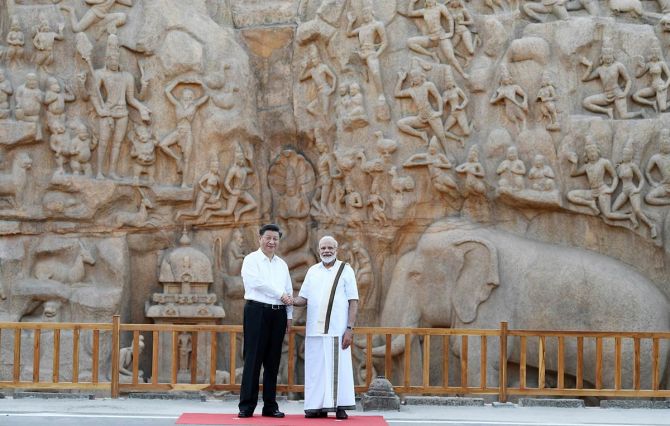

From the very start, PM Modi was insistent that visiting foreign leaders should be exposed to an India beyond its capital.

Through these experiences, he felt that the full Indian narrative would be much better understood across the world.

And sure enough, Amritsar saw a ‘Heart of Asia’ Conference, Goa a BRICS Summit, Kashi and Ahmedabad visits by Shinzo Abe, Bengaluru and Chandigarh by Angela Merkel and Francois Hollande respectively, and Mamallapuram by Xi Jinping.

He was also keen that the federal nature of our polity be factored into policymaking, leading to the establishment of a States Division within MEA.

Partnerships, events and visits organized with state government collaboration rapidly became the norm.

And their cumulative result broadened the message of Indian diplomacy.

The perseverance that has driven the transformation of Gujarat in the past two decades is now also in evidence when it comes to India’s projects abroad.

The Pragati model of project review instituted at the national level has led the Foreign Ministry to follow similar practices for its own endeavours abroad.

As a result, long-pending projects like the Terai roads in Nepal, housing and hospitals in Sri Lanka, rail connectivity and power transmission in Bangladesh or the Salma dam and public buildings in Afghanistan were finally completed.

And the new ones undertaken have been executed at a much faster pace, denoting the improvement in the manner of delivery.

Whether it is the Metro or Supreme Court in Mauritius, post-earthquake rebuilding of houses in Nepal or the ambulance service in Sri Lanka, India’s reputation as a development partner has undergone a sea change.

Among the Prime Minister’s many attributes, one that stands out is his deep sense of nationalism.

This is, of course, intrinsic to his political beliefs and one very much in evidence even when he was Chief Minister.

When I first met him as Ambassador in China in 2011, unlike many other Chief Ministers, he specifically sought a political briefing.

I recall his emphasizing that on issues of terrorism and sovereignty, we needed to make sure that we spoke with one voice abroad; especially in China.

This, incidentally, was also my first exposure to his method of working.

Among the takeaways was insistence that I should not hesitate to indicate clearly what he should say, and equally, what he should not say.

His letter on return to India went beyond the normal appreciation that visitors express for hospitality, etc.

What was different was a pointed mention of my successful upholding of the interests of our country in China.

As Prime Minister, it was only to be expected that he would be confronted with national security challenges, on a recurring basis and on occasion, as a crisis.

When it came to terrorism, especially of a cross-border nature, he has been crystal clear that he would never allow it to be normalized.

This determination has shaped our Pakistan policy since 2014.

My own recollection in this regard goes back to the SAARC Yatra that I was undertaking soon after becoming Foreign Secretary in 2015.

In his parting instructions, the PM told me that he had great confidence in my experience and judgement, but there is one thing I should keep in mind when I arrive at Islamabad.

He was different from his predecessors and would neither overlook nor tolerate terrorism.

There should never be any ambiguity on this score.

Insofar as China is concerned, Prime Minister Modi is a firm believer that our relationship should be based on mutual respect and mutual sensitivity.

He recognizes that we are two unique civilizations whose near-parallel rise poses its own challenges.

In all the meetings with Chinese counterparts that I have been present, he has never held back from voicing our interests and concerns.

Excerpted from Modi@20: Dreams Meet Delivery by Bluekraft Digital Foundation, with the kind permission of the publishers, Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd.

Source: Read Full Article