Technological solutions to make rice and sugarcane cultivators use water more sustainably can work if there are right incentives, and agri-input pricing is on the right track.

On World Water day (March 22) Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the “Catch the Rain” campaign under the government’s flagship programme, Jal Shakti Abhiyan. He emphasised the importance of using every penny spent under MGNREGA to conserve water. This is a laudable objective. But what is the state of our water resources? How can we ensure that everyone has access to safe drinking water, while industry and agriculture also get sufficient supplies to produce enough to meet the country’s demands? These issues demand close attention.

As per the Central Water Commission’s reassessment of water availability using space inputs (2019), India receives a mean annual precipitation of about 3,880 billion cubic meters (BCM) but utilises only 699 BCM (18 percent) of this; the rest is lost to evaporation and other factors. The demand for water is likely to be 843 BCM in 2025 and 1,180 BCM by 2050. So, the targets are not beyond our reach, if we remain focused and follow an appropriate strategy that not only “catches more rain” but also ensures better demand management of this precious resource.

As per the UN’s report on Sustainable Development Goal-6 (SDG-6) on “Clean water and sanitation for all by 2030”, India achieved only 56.6 per cent of the target by 2019. This indicates that we need move much faster in order to meet this SDG goal. Further, as per the Niti Aayog’s Composite Water Management Index (2019), 75 per cent households in India do not have access to drinking water on their premises and India ranks 120th amongst 122 countries in the water quality index. India is identified as a water stressed country with its per capita water availability declining from 5,178 cubic metre (m3)/year in 1951 to 1,544 m3 in 2011 — this is likely to go down further to 1,140 cubic metre by 2050.

How does one move forward? Agriculture uses about 78 per cent of fresh water resources. And as the country develops, the share of drinking water, industry, and other uses is likely to rise. Unless one learns to give effect to the credo of “per drop more crop” in agriculture, the challenge can be daunting. We need a paradigm shift in our thinking and a strategy to not just increase land productivity measured as tonnes per hectare (t/ha), but also maximise applied irrigation productivity measured as kilogrammes, or Rs, per cubic metre of water (kg/m3).

So far, with decades of large public and private investments in irrigation, only about half of India’s gross cropped area (198 million hectares) is irrigated. Groundwater contributes about 64 per cent, canals 23 per cent, tanks 2 per cent and other sources 11 per cent to irrigation. This results primarily from the skewed incentive policy of free or highly subsidised power, particularly in the country’s north-west, the site of the erstwhile Green Revolution. Over exploitation of groundwater has made this region amongst the three highest water risk hotspots, the others being north eastern China and south western USA (California). Overall, about 1,592 blocks in 256 districts in India are either critical or overexploited.

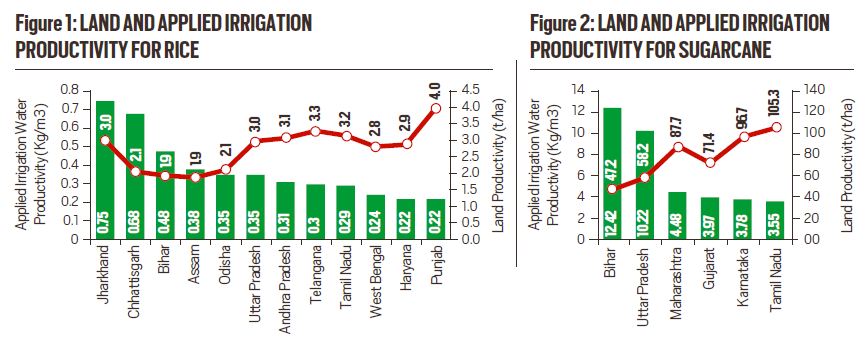

When it comes to the issue of using water more wisely in agriculture, two crops — rice and sugarcane — deserve special attention. As per a NABARD-ICRIER study on Water Productivity Mapping, these crops alone consume almost 60 per cent of India’s irrigation water. Figure 1 shows applied irrigation water productivity against land productivity for rice and sugarcane in important growing states. It is interesting to note that while Punjab scores high on land productivity of rice, it is at the bottom with respect to applied irrigation water productivity. Similarly, in the case of sugarcane, irrigation water productivity in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu is only 1/3rd of that in Bihar and UP (Figure 2). There is, thus, a need to realign cropping patterns based on per unit of applied irrigation water productivity.

There are technologies to produce the same output of these two crops with almost half the irrigation water. Jain Irrigation, for instance, has set up drip irrigation pilots for paddy in Karnal (Haryana) and Tamil Nadu and for sugarcane in Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. The results of these pilots indicate while it takes 3,065 litres of water to produce 1 kg of paddy grain (yield level 7.75 t/ha) under traditional flood irrigation, under drip, it can be reduced to just 842 litres. The benefit cost ratio of drip with fertigation in case of sugarcane in Karnataka is observed to be 2.64. An extension to this is the “Family Drip System” innovated by the largest drip irrigation company in the world, the Israel-based — Netafim. The company has also launched its largest demonstration project in Asia at Ramthal, Karnataka. Technologies like Direct Seeded Rice (DSR) and System of Rice Intensification (SRI) can also save 25-30 per cent of water compared to traditional flood irrigation. Unfortunately, however, technological solutions cannot make much headway unless pricing policies of agri-inputs are put on the right track and farmers are incentivised for saving water.

The Punjab government, along with the World Bank and J-PAL, has started some pilots with an innovative policy of “Paani Bachao Paise Kamao” to encourage rational use of water among farmers. Under the initiative, meters are installed on farmers’ pumps, and if they save water/power compared to what they have been using (taken as entitlements) they get paid for those savings — this is credited directly into their bank accounts.

Overall, it seems it is time to switch from the highly subsidised price policy of water/power (and even fertilisers) to direct income support on a per hectare basis, and investment policies that help with newer technologies and innovations. Water and power need to be priced as per their economic value or at least to recover significant part of their costs to ensure sustainable agriculture.

This article first appeared in the print edition on March 29, 2021 under the title ‘Time to make the water switch’. Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture and Juneja is a Consultant at ICRIER

Source: Read Full Article