The dark cloud which seems to hang over the Imagine spirit may have little to do with material circumstances and more to do with our failure to locate the spirit in the completeness of life.

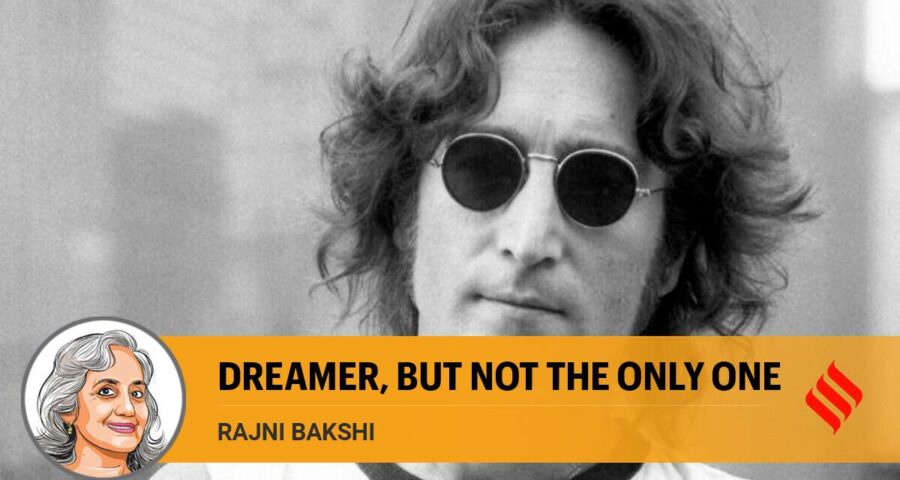

John Lennon’s Imagine turns 50 tomorrow. Though a song cannot be pinned down to one day, it was on July 4, 1971, that finishing touches were put on the recording of Imagine. It was released in an album later that year.

How might we honour, or just respond to, this poignant anniversary? What is the bittersweet significance of Lennon’s dream of a world living as one? Should his longing for universal brotherhood be dismissed as futile because Lennon himself was killed by a “fan” who, among other reasons, was incensed by Imagine?

At a time when identity-based hatred is diversely justified across the world, it is easy to feel entrapped in a pessimistic view of human societies. For those so afflicted, Imagine can be little more than a hippie fantasy.

Most of us know people who feel offended by Lennon’s proposition that there is neither heaven nor hell, “above us, only sky”. Add to that the vision of “no countries”, “no religion”, “nothing to kill or die for” — and opposition is inevitable.

Long after the defeat of communism, Lennon’s appeal that we “imagine no possessions”, can be ridiculed by anyone who is invested in a global economic culture that requires an endless desire for more material goods and purchasable experiences.

Of course, Lennon’s lyrics anticipate this disdain. Thus, the refrain of the song is, perhaps, even more famous than its title: “You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.”

Whether or not he intended it, this puts Lennon in the company of anarchists — and that does not mean rebels who throw bombs at kings and other rulers. Here, the term anarchist refers to all those who have been inspired by the rallying cry — “Demand the impossible”.

When Gandhi insisted that with the power of love and truth, one’s opponent can be persuaded to have a change of heart, he was reaching beyond the conventional “possible” in politics.

When a wide range of bhakti poet-saints across India, through different times, urged us to look for god within and find divinity in our fellow travellers, they were turning the impossible into possible.

So, one way to honour the anniversary of Imagine is to locate it in the wider reality within which it was written. After all, Lennon later gave interviews saying that much of the song was taken from Yoko Ono’s book Grapefruit.

The Indian dimension of the Imagine spirit is still older. Sahir Ludhianvi’s Woh subah kabhi to aayegi was written in 1958. Shailendra wrote Kisi ki muskurahaton pe ho nisaar in 1959. Kishore Kumar wrote Aa chalke tujhe main leke chaloon in 1964. These sterling examples of still-living, often-sung songs, show how this spirit has had a life of its own in India’s popular culture.

If you are a die-hard sceptic, it is easy to dismiss these songs as a poet’s fantasy. But these poets were not preoccupied with a Neverland. Instead, they were expressing hopes and ideals that had tangible political form in their times. This was notably manifested in, but not limited to, the Progressive Writers’ Association.

The songs referred to above reaffirmed an ancient human longing — to live peacefully with each other and with the natural world. They drew simultaneously on ancient roots, like the Sanskrit prayer in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad which begins “Sarve bhavantu sukhinah” (may all sentient beings be at peace) as well as on a contemporary politics of brotherhood and unconditional dignity for all.

These aspirations were never limited to, or containable in, specific ideologies — be it communism, socialism or any shade of liberalism.

Today, in part, the Imagine spirit is manifest in certain regional terms becoming globally familiar. So ubuntu from Africa, which roughly translates as “you are therefore I am”, inspires people across the world. From Latin America, buen vivir, the good life, carries the same resonance of mutual aid and fruitful interdependence. From India sarvodaya, well-being and upliftment of all, is invoked across the world by those who — as Lennon urged — “imagine all the people, sharing all the world”.

The dark cloud which seems to hang over the Imagine spirit may have little to do with material circumstances and more to do with our failure to locate the spirit in the completeness of life.

We can more rigorously live by this spirit if we take to heart what I learnt from Om Prakash Rawal, a gentle Gandhian-socialist politician from Madhya Pradesh. In the 1980s, Rawalji was an elderly guiding light at many activist gatherings, where at some point we inevitably sang Aa chalke tujhe main leke chaloon. One day Rawalji reflected on the second line of the song about a world with no tears, no sorrow and only love.

“How can this be?” he asked. “How can there be love in a world where there is no sorrow?”

This column first appeared in the print edition on July 3, 2021 under the title ‘Dreamer, but not the only one’. The writer is an author and founder of the online platform ‘Ahimsa Conversations’.

Source: Read Full Article