Jayaprakash Narayan was the People’s Hero, a leader unmatched in Independent India.

Archana Masih/Rediff.com travels to JP’s village looking for Bihar’s greatest son as the claimants of his legacy go to war in what is being called the Election of Elections.

This is where the borders of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh meet.

The two great states of the Hindi Heartland are divided by the Ghagra or Saryu in western Bihar. A river beautifully named, but one that has proved to be a vicious destroyer when its waters break the banks and ravage everything in their path.

Across the river, the road runs on a bund lined by huts of people who have moved to higher ground after their homes were destroyed by the floods.

Their cots lie out on the road in the sun. Their corn is drying out by the roadside. Their children play.

I am looking for JP. It is a pilgrimage to see one of India’s greatest icons.

A man of great moral standing on whose call, students, netas and thousands of Indians joined a movement to overthrow a powerful leader.

A man whose legacy is claimed by all the leading men of Bihar politics, leaders who took their baby steps in politics in the JP movement.

But it is not easy to find JP. There are no boards and you have to ask villagers at every turn, which leads to Jayaprakash Nagar in Ballia, UP. It is a hot afternoon and there are only a few people that can be spotted in the neat village. A startled neel gai (the Indian blue bull) nearly jumps onto the car’s bonnet.

The search ends at a nicely maintained house that I am told was JP’s home. Inside I learn there is another house that claims to be JP’s and that lies in Lala Tola, a short distance from here, in Bihar. The Modi government recently declared the construction of a memorial in Lala Tola.

Though JP was born when Bihar was part of the Bengal Presidency, his village, Sitab Diara, straddles both UP and Bihar. And that is the reason for the tug-of-war.

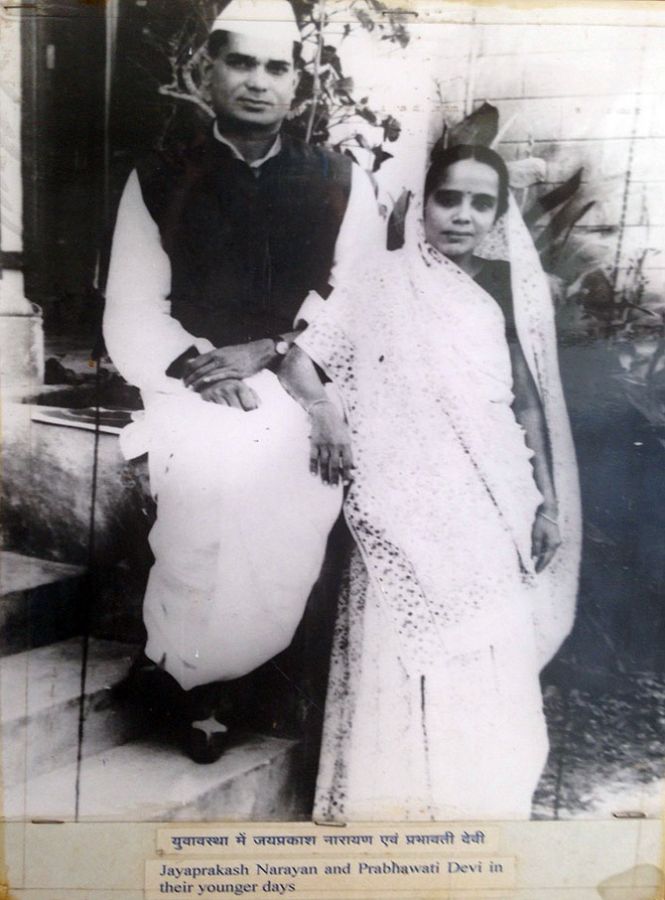

This one is a charming house, lined with beautiful crotons. A verandah leads to an inner courtyard which is bordered by rooms. Antique easy chairs lie lazily in the verandah. A meshed room contains a dining table with brass untensils used by JP and his Gandhian wife Prabhavati Devi. On the other side is JP’s bedroom.

It is a sparse room. Two beds on either side, his slippers on the floor, coat in a glass case on the wall and a photograph with Rabindranath Tagore hanging on the opposite wall.

“Not many people come to visit,” says Rajnikanth Prasad, a staffer at the trust that looks after the house and adjoining museum.

Rajnikanth opens the museum which is well maintained and has on display many letters, articles and some photographs documenting JP’s journey from the freedom movement to the 1970s.

I notice how JP addressed his letters to Jawaharlal Nehru as ‘Bhai’ and to Indira Gandhi as ‘Indu.’ There are letters from Gandhiji and also a letter by J R D Tata expressing his admiration.

There are some newspaper cartoons showing his moral high ground before the Emergency, the dark 19 months in Independent India’s history when ‘Indu’ suspended individual freedoms and democracy.

For a man who contributed so much to India’s journey — from the freedom movement to socialism, the Bhoodan movement — JP’s many contributions have unfortunately been sidelined to his pre and post Emergency roles in India’s history.

It was certainly not the sum of all his parts and the museum captures his other important contributions in the shaping of our nation.

Outside the immaculate gardens and mango trees that border the house and museum, I look for Lala Tola, the other place that is said to be the place of JP’s birth.

Down the narrow road which again bears no boards or signs, Lala Tola is a long way off the main road. This is the only village across the Ganga where newly-made toilets can be spotted.

A bust of JP is placed outside a house which locals point out as JP’s house.

It is a crumbling house, its thatched roof propped up by a log of wood. It is messy, a bed lies in the verandah and large pictures of JP’s journey hang from the cracked walls.

I am greeted by an old lady. Her name is Phunni Devi. She has white hair, walks with a stick and warmly insists that I sit down and have some biscuits.

She is the wife of JP’s younger brother, she says, and arrived from Kolkata before his birth anniversary on October 11 when BJP President Amit Shah had come to pay tribute and participate in the bhoomi pujan to construct the memorial.

“The house that JP was born in was by the river,” she says, “But it got washed away in the floods.”

One of the rooms has a plaque saying Prabhavati Devi library, a few books lie in the dust inside. In another room, a mosquito net is strung up on an old bed.

Phunni Devi does not know whether the government will restore this house that belongs to her where she now lives alone. A caretaker helps her with her daily needs.

She comes to the door to say goodbye. The sun is setting behind her.

There is confusion about JP’s place of birth and there has been constant political wrestling about his legacy — like it does with the legacies of many of India’s leaders.

As I leave Sitab Diara and go over the bridge on the Saryu, under a signboard which says ‘Welcome to Bihar,’ I look at photographs of the museum I have taken on my phone.

One of JP’s messages pasted on the museum wall stands out:

‘Politics, at least under a democracy, must know the limits it may not cross. Otherwise, if there is dishonesty, corruption, manipulation of the masses, naked struggle for personal power and gain, there can be no socialism, no welfarism, no government, no public order, no justice, no freedom, no national unity — in short, no nation.’

It is a message that the leaders of today must heed. Unless they do, the search for JP will continue. We may keep looking for him, but may not find him.

Postscript: Ramdhari Singh Dinkar’s poem: Singhasan khaali karo ki janta aati hai (Vacate the throne because its true claimants, ‘the people’, are here to claim it), was recited by JP at the Ramlila Grounds in New Delhi in June 1975.

Dinkar, like JP, belonged to Bihar. The poem also has a verse which broadly translated means: Why do you search for your Gods in temples and palaces

The gods can be found laying roads

The gods can be found toiling in the fields…

As Bihar goes to the polls, its leaders — and in fact, all the leaders of this country — should reflect on the great poet’s words and work for these lesser Gods. It is in their service where India’s leaders will find real salvation.

This is the concluding feature in the ‘I Am Bihar’ series, on the day Saran, the district that JP hails from, goes to the polls. There could be no better way to sign off than by remembering the man who can truly be called a worthy claimant to that title.

I AM BIHAR SERIES

- ‘The farmer is the most stubborn of men’

- ‘Once someone fired a gun at my show’

- ‘No one in my family knows what IIT is’

- ‘When you’re in the ring, you know no fear’

- ‘It’s a boy!’

- A midday meal with Kareena

- ‘Education gives me confidence to survive in an unequal world’

- ‘They built 20 toilets. Not one is fit to be used now’

- Mobile phone has reached her, but bijli hasn’t

- ‘They shoo the poor as if they are dogs’

Source: Read Full Article