Hundreds of Pakistani Hindus have migrated to India in search of security and citizenship but are caught in a maze of rules and regulations that have left them stateless for years. Mohammed Iqbal reports on their plight and the politics around citizenship

Maharaj crossed the border into India with nine family members in August 2000. He decided to stay in the country, in Jodhpur, to escape the economic hardship and discrimination he was facing in Rahimyar Khan district in the Punjab Province of Pakistan. “Our father passed away waiting for citizenship. Our family has 19 members and we have nowhere to go,” says Harjiram Bheel, Maharaj’s son.

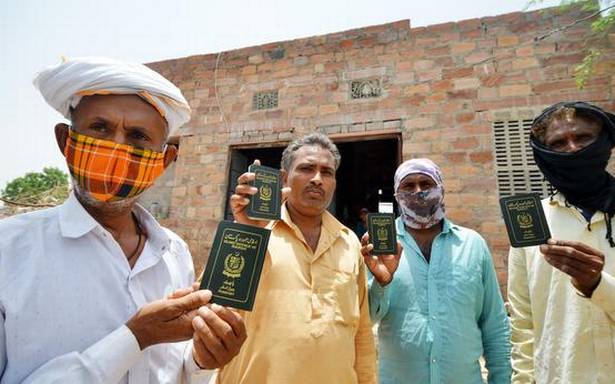

Bheel says the family has been wandering from one citizenship camp to another over the years. These camps were organised by the Union Home Ministry from time to time to receive new applications for citizenship and dispose of or clear old ones. But the camps have not been successful because of red-tapism. Bheel’s family is one among many whose Pakistani passports and Indian visas have expired.

Karamshi Koli, 43, who migrated to India in 2015, lives as an asylum-seeker in the Anganwa hutment. Koli says he has not even succeeded in getting a long-term visa which would enable him to find a private job or take up self-employment to sustain his family.

The weary residents of the mud houses in Anganwa, adjacent to a water filtration plant, have no access to electricity, water, toilets and sanitation facilities. Women and children fetch water from a well in the Shri Khetanand temple situated 2 km away, while solar lights — some donated by philanthropists and some purchased by some of the migrants — are used at night.

The number of Pakistani Hindu migrants staying in 21 settlements in Jodhpur district is estimated to be about 30,000. The land where they have built their ramshackle dwellings belongs either to the Municipal Corporation or the village panchayats and Forest Department. These migrants came to India expectantly, but their eagerness has turned into disillusionment over time. They are unhappy with the way they are being treated in a country which they had hoped would accept them wholeheartedly and they could call home.

No sense of belonging

Young Laxman Singh, who hails from Sindh’s Mirpur Khas district, says unhappily that migrants like him seem to belong nowhere. “We faced persecution on the ground of our religious identity in Pakistan. In India, we are being ostracised for being Pakistanis,” he says. Most men like him, who were landless farmers or daily labourers in Pakistan, have failed to find any gainful employment in or around Jodhpur. The pandemic-related lockdowns have only made matters worse.

Hemji Koli, who is a shelter manager on a contractual basis with the Municipal Corporation, runs a ‘Chetana’ study centre on behalf of a non-governmental organisation, Universal Just Action Society, in the Anganwa settlement. The centre provides basic literacy to children up to five years of age and tuition to those going to nearby government schools. About 350 children who were attending school before the COVID-19 outbreak have been confined at home for over a year due to the pandemic.

Pakistani Hindu migrant children return after fetching water from a well located more than 1.5 km away from their Anganwa settlement in Jodhpur district of Rajasthan. | Photo Credit: R.V. Moorthy

“No person in this locality has been given citizenship so far. This is a relatively new settlement. The only saving grace is that we have not been driven out of this land,” Hemji says. Some migrants in the other settlements have got citizenship after completing the mandatory 11 years of stay for eligibility under the Citizenship Act of 1955, but even they struggle daily to get food, water, healthcare and education.

Since 2014, most Hindu migrants have been entering India, into western Rajasthan and northern Gujarat, on a pilgrim visa. They often leave their family members in Pakistan in the hope that they can travel later when they find employment in India. However, they are invariably disappointed when they are left to fend for themselves.

The migrants are mostly Dalits from the Meghwal, Koli, Bhil, Jatav, Kumawat and Mali communities. They are considered underprivileged on both sides of the international border, though some caste Hindus, belonging to the Rajput, Maheshwari and Brahmin communities, have also crossed into India.

They all say that they were segregated and persecuted in Pakistan on religious grounds. They say young girls are sometimes abducted and forcibly converted to Islam in the interior areas of Sindh. Their children faced discrimination in government schools. Their shops and commercial establishments were attacked by robbers. And Hindu residents were not allowed to buy property.

Hindu Singh Sodha, president of the Seemant Lok Sangathan, an organisation working for the welfare of migrants, points out that there have been three waves of migration of Hindus to India from Pakistan. The first was during and after Partition. During the 1971 war, about 90,000 persons migrated to India when Indian troops strategically occupied important areas 50 km deep inside Pakistan. The third wave, which started as a result of a backlash against Hindus during the Ram temple movement and after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, has been a prolonged one. Migrants still continue to come to India. Also, in 1996, the Taliban captured power in Afghanistan. This led to a change in atmosphere in Pakistan, with the minority communities in the Balochistan and Sindh Provinces increasingly being targeted.

A maze of rules and regulations

While a growing sense of insecurity in Pakistan has led to the migration of thousands of Hindus over the past two decades, they cannot expect to get the status of refugees because India is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, nor its 1967 Protocol. The Pakistani immigrants do not receive the protection or benefits which they would have been entitled to on getting official refugee status if India had been a signatory.

All foreign nationals, including asylum-seekers, are governed by the provisions of the Foreigners Act, 1946; the Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939; the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920; and the Citizenship Act, 1955, as well as the rules and orders framed under these laws. The Union government possesses the power to detain and deport foreigners and restrict their movements, but it has no international obligation to enact a legislation for refugees.

For accessing legal entitlements and services, Indian citizenship is the only viable option for the migrants. But the migrants face major challenges in obtaining citizenship status, ranging from the condition of having stayed in India for a certain number of years to keeping the registration permit from the Foreigners Regional Registration Office up-to-date and paying a hefty fee for frequent renewal of their long-term visas.

Having all the Indian documents is not enough. The migrant must also hold an unexpired Pakistani passport, which can only be obtained at the Pakistan High Commission in New Delhi. Bhagchand Bhil, who left his medical practice in Karachi and crossed the border in 2014, says that most of the migrants are illiterate and unable to decipher and navigate this maze of rules and regulations, which makes them vulnerable to deceit and exploitation by government officials.

Even when they do get citizenship, their problems don’t end. Obtaining documents such as ration cards and caste certificates is no easy task and they find it difficult to avail themselves of the benefits of the government’s healthcare, education and employment schemes. Sodha, who had himself migrated as a young boy from Tharparkar district’s Chachro town in 1971, rues that there is no provision for the rehabilitation of people from Pakistan.

The Seemant Lok Sangathan has raised these issues repeatedly with the Union Home Ministry over the past few years. While affirming that the government needs to be migrant-friendly, Sodha has sought the grant of citizenship through special camps, which will benefit the migrants who still have their family members in Pakistan. “During the last 30 years, I have not found a single family which says it has no member over there. The families are divided,” he says.

Moreover, the gaps in livelihood development and rehabilitation status should be identified at the State level and a robust policy for rehabilitation introduced at the Central level for migrant families, he says. Stateless persons belonging to higher castes, who comprise 20% of the migrant population, manage the hardship better because of their socioeconomic condition. They are generally engaged in business or private employment.

Also read | Post Partition, Dalit refugees from Pakistan continue to suffer

The children of these migrants are the worst affected. Schools reluctantly give them admission and do not provide them emotional support and counseling. The children struggle as their medium of instruction was Urdu and Sindhi in Pakistan and Hindi in India. They are often singled out by the teachers and other students because of their Pakistani origin. Government schools, which earlier demanded their identity proof, started giving them admission only a couple of years ago.

Despite this, some migrant children have excelled in their studies. Chandra Prakash, son of a migrant teacher, Manjhiana Rana, topped Class 12 at the Maulana Abul Kalam Azad School, run by the Marwar Muslim Educational and Welfare Society, in 2019. Chandra Prakash is now studying MBBS at the Sardar Patel Government Medical College in Bikaner.

The Marwar Muslim Educational and Welfare Society’s CEO, Mohammed Atiq, says plans are afoot to open a primary school this year exclusively for the children of migrants at a plot of land situated near the Maulana Azad University in Bujhawar village. The school will be gradually upgraded to include higher education after the intake of 60 children in the first year.

As an indication of the State government’s consideration for the rehabilitation of the migrants, Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot inaugurated the Vinoba Bhave Nagar housing scheme for them, comprising 1,700 plots at the land measuring 300 bighas, in Chokha village near Jodhpur earlier this month. The residential scheme, announced in the 2021-22 State Budget, will be executed by the Jodhpur Development Authority.

Hope and despair

On the one hand, the government is making efforts to improve their quality of life, but on the other, the migrants have also had to face the problem of exploitation by government officials. In May 2018, a racket involving extortion of money from the migrants for extension of long-term visa, visa transfer, and grant of citizenship came to light after the arrest of a Home Ministry official by the Rajasthan Anti-Corruption Bureau. The official visited Jodhpur regularly to attend hearings on writ petitions moved by the migrants in the Rajasthan High Court. The official had three agents who identified themselves as Pakistani migrants with Indian citizenship. The case indicated that a larger nexus was at work to exploit the migrants for money. The Anti-Corruption Bureau’s probe revealed that the official had demanded and accepted bribes from about 3,000 migrants in 2017 alone.

The inordinate delay in the grant of citizenship has led to a host of problems for the migrants. In November last year, a migrant woman, Janta Mali, was reunited with her family in western Rajasthan after being stranded in Pakistan for 10 months during the lockdown. Since her No Objection to Return to India (NORI) visa had expired, she was not allowed to travel back. Mali’s husband and children, who are Indian citizens, travelled back to India in July 2020 after visiting her ailing mother in Pakistan’s Mirpur Khas. The Seemant Lok Sangathan took up the issue with the Rajasthan government and the Centre and succeeded in bringing her back after six months by getting her visa extended.

Though the migrants have been staying in cities in western Rajasthan such as Barmer, Jaisalmer and Bikaner for several years, Jodhpur emerged as the preferred destination after the Thar Express train linking Karachi with Bhagat Ki Kothi railway station started in 2006. The train was stopped in August 2019 when tensions escalated between India and Pakistan following India’s revocation of special status to Jammu and Kashmir. The Munabao-Khokhrapar rail route was restored after a gap of 41 years following the 1965 war to reduce the distance and journey of time for people from central and southern Indian States travelling to Pakistan. It gained popularity among the Pakistani Hindus who wanted to migrate to India. The train was also used by migrants frustrated by the delay in the grant of long-term visa or citizenship to return to Pakistan.

While the Collectors of Jodhpur, Jaipur and Jaisalmer districts were empowered to grant citizenship in 2016, the new notification has now delegated the same powers to the Collectors of Jalore, Udaipur, Pali, Barmer and Sirohi districts. Sodha says these powers should be conferred on the Collectors of all districts in the State to speed up the process of application, security check, and inquiry for grant of citizenship.

The Home Ministry says that the latest notification is not related to the contentious Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) of 2019, which has not come into effect and seeks to benefit the undocumented or illegal migrants from the six “persecuted communities” who entered India before December 31, 2014. The CAA will reduce the requirement of 11 years of aggregate stay in India to five years for citizenship, which would help fast-track the applications of migrants.

The president of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties in Rajasthan, Kavita Srivastava, disagrees. She says that the notification amounts to implementation of the CAA “by stealth” even as the law has been challenged in the Supreme Court. “The delegation of powers to the Collectors is only with respect to the communities covered by the CAA and not those otherwise eligible for citizenship by registration and naturalisation,” she says. While demanding immediate withdrawal of the notification as well as nullification of the CAA, Srivastava says the notification’s intention is to rush through citizenship without waiting for the court’s verdict. She says it is also in complete disregard to the massive protests against the law in late 2019 and early 2020. “It is the first salvo towards implementing the 2019 Act, as its intention is to keep Muslims out of the purview of the citizenship law,” she says.

Civil rights groups have called for taking measures to smoothen and hasten the process for grant of citizenship to migrants irrespective of their religious identity. Popular Front of India’s State president Mohammed Asif says the organisation will stage protests against the May 28 notification in a democratic manner once the COVID-19-related restrictions are lifted, as it bears resemblance to the CAA which discriminates on the ground of religion.

COVID-19-related problems

A new issue that the migrants are now facing is inaccessibility to vaccines. This remains unresolved despite the intervention of the Rajasthan High Court. The State government has refused to inoculate those who do not possess Aadhaar cards or other prescribed documents. About 15 migrants, including those who tested positive for COVID-19 and those suspected to have the virus or are symptomatic, have died in Jodhpur during the second wave of infections.

A Division Bench of the High Court, which earlier ruled that the Centre’s standard operating procedure on vaccination did not exclude the migrants from Pakistan, has hauled up the State government for seeking clarification from the Union government, and sought an explanation from the Chief Secretary. The migrants settled in Barmer have started getting vaccinated on the basis of their Pakistani passports.

Hearing the additional submissions made on behalf of the migrants in a suo motu case, the court also directed the State government to supply ration material and food packets to them through the Food and Civil Supplies Departments, local bodies and non-governmental organisations. It was submitted to the court that only the migrants residing in Jodhpur were getting the food packets, while those in Jaisalmer, Barmer and Jaipur districts were deprived of food supply during the pandemic.

Hoping against hope that their basic needs will be met, the Pakistani Hindu migrants are caught in a vicious circle of poverty and vulnerability. They face an unresponsive government and uncertain legislation. Out of their homeland and across the border, the migrants wait endlessly for the day when they can call India their true home.

Source: Read Full Article