Very few today realise that without Brigadier John Dalvi’s courage, we would never have known what really happened during those tragic days of October/November 1962, reveals Claude Arpi.

Today we are celebrating the 100th birth anniversary of John Parashuram Dalvi who commanded the ill-fated 7 Infantry Brigade on the Namkha chu (river) in the West Kameng Frontier Division of the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA) in October 1962.

Very few today realise that without his courage, we would never have known what really happened during those tragic days of October/November 1962.

When Brigadier John Dalvi returned to India on May 4, 1963, he and his 26 junior colleagues were interrogated like criminals, the government suspecting them to have been brain-washed by the Communist Chinese.

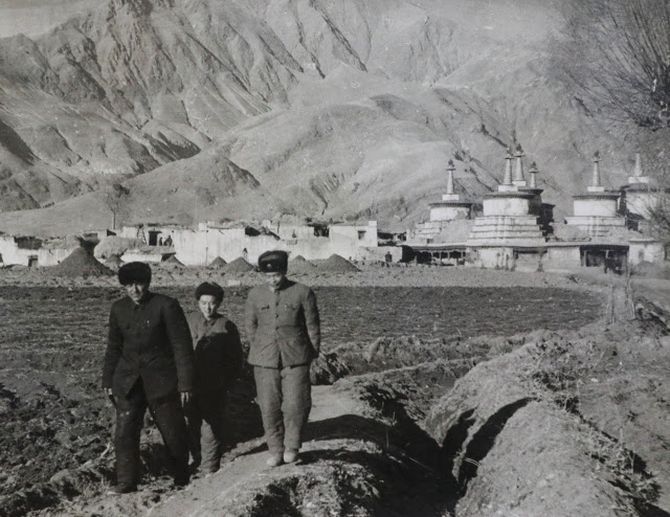

According to his family, this was even more difficult to bear than his days in captivity; he had been kept in a separate camp near Tsethang in Central Tibet, far from his men, in complete disregard of the Geneva Conventions. I have written about this on this blog (external link).

Later, Brigadier Dalvi was offered a second star (to be promoted as Major General) by a senior minister of the Nehru government to keep quiet.

He preferred to write about what really happened; he was never promoted.

His Himalayan Blunder had to first be published in the UK by his sister as no publisher in India dared accepting such a manuscript. It was only years later, that it was released in India.

Can you imagine what would have been our knowledge of the history of the conflict if Brigadier Dalvi had not penned his memoirs?

Remember that today, the Henderson-Brooks-Bhagat report is still kept under wraps at army headquarters.

As I was writing this tribute, I received this message from Michael Dalvi, Brigadier J P Dalvi’s son. It is very touching:

A SON’S HUMBLE TRIBUTE

The man you see here in uniform, in which he took such great pride, joy and honour, would have been 100 years of age today.

It is my honour, privilege and pride to be his son.

He is flanked by insignias of the Indian Army and his beloved Battalion, the 4th (Rajput) Guards.

Commissioned (Indian Military Academy, Dehradun) at age 21 he went straight off to do battle with the Japanese in Burma with his Regiment, 10/5 Baloch.

In 1962, he went off to do battle again. This time the Chinese, as Commander 7 Brigade then based in Tawang. NEFA.

Our collective energies are currently deeply absorbed in the Chinese challenge facing our nation.

It is as good a time as ever, indeed imperative, that at this crucial and critical time, we honour and respect the memory of the bravest of the brave of our warriors who have selflessly done battle before in the service of our nation.

And learn from the hard lessons of history.

Never ever again must a proud commander of the finest fighting men in the world have to go to a premature grave with the deaths of his men and officers on his conscience.

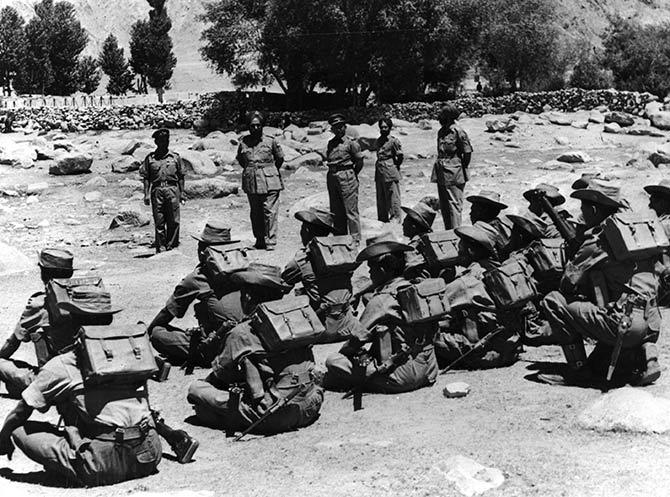

That his troops, under-clothed, armed with obsolete weapons, under fed and woefully ill-equipped for mountain warfare fought to the bitter end is a tribute to the discipline, training, fortitude and indomitable spirit of the Indian Army.

They died with honour, often, to the last man and the last bullet and not before inflicting huge casualties on an enemy militarily and psychologically unprepared for such intrepidness!!

We must never forget that fact, sitting in the cozy comfort of our safe houses rendered secure by the daily sacrifice of our troops!!

To quote Macaulay:

And I pray God that no man should have to witness his father’s gradual but inexorable mental and physical deterioration and decline.

From a conscience debilitatingly burdened, tormented, riddled with bitterness, anger, frustration helplessness and guilt for those who didn’t make it back!!

This guilt eventually destroyed his soul. It gnawed at the very core of his being from living each day with the memory of men of steel who followed blindly, into impossible situations, against unimaginable odds, and in many cases certain death, driven to great heights of valour only for the Izzatof their paltans, their army, and the honour and security of their country!!!

And let the guilty, and their political successors contemplate, the great crime of sending brave men to do battle against AK-47s with WWI obsolete.303 Lee Enfield bolt action rifles !!!!

And with not enough ammunition to fight a relentless enemy. Often resorting to hand to hand combat and using the weapons of fallen Chinese soldiers!!!

These were criminals. Make no mistake about that. History has labelled them thus. For the sheer brazen and brutal heartlessness of their crimes of omissions and commissions against a simple, trusting, loyal and dedicated soldiery!

I only hope those who currently control and conduct the destiny of our great country, and our unquestioning uniformed bravehearts learn from the hindsight of history!!

It’s done and dusted sir. You are dead and gone ages ago, but your army, that was your life, lives and fights on!!!

RIP Sir wherever you be, and, hopefully, till we meet again to clink pewter tankards of your favourite tipple; chilled to perfection!!!

MICHAEL DALVI

In homage to Brigadier Dalvi, on the occasion of his 100th birth anniversary, I post here — with Mr Michael Dalvi’s kind permission — the preface of his book — The Himalayan Blunder, Brigadier J P Dalvi, Natraj Publishers (2009) — which is so relevant with the present happenings in the Himalayas.

‘This book was born in a Prisoner of War Camp in Tibet on a cold bleak night.

On the night of 21st November 1962, I was woken up by the Chinese Major in charge of my solitary confinement with shouts of ‘good news – good news’.

He told me that the Sino-Indian War was over and that the Chinese Government had decided to withdraw from all the areas which they had overrun, in their lightning campaign.

When I asked the reason for this decision he gave me this Peking inspired answer: ‘India and China have been friends for thousands of years and have never fought before. China does not want war. It is the reactionary (sic) Indian Government that was bent on war. So the Chinese counterattacked in self-defence and liberated all our territories in NEFA and Ladakh, in just one month.’

‘Now we have decided to go back as we do not want to settle the border problem by force. We have proved that yonu are no match for mighty China.’

He concluded with this supercilious and patronising remark: ‘We hope that the Indian Government will now see sense and come to the conference table at once so that 1,200 million Chinese and Indians can get on with their national development plans and halt Western Imperialism.’

This kindergarten homily was, and remains, the most humiliating moment of my 7-month captivity and indeed of my life. That night I experienced a wave of bitter shame for my country.

In my grief I took a solemn vow that one day I would tell the truth about how we let ourselves reach such a sorry pass.

With time heavy on my hands, as I had no radio, newspapers or books, I brooded over India’s humiliation and the fate of my command.

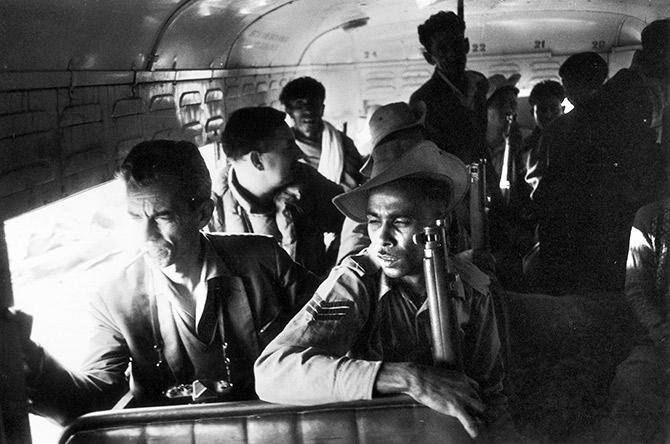

I was repatriated, along with all the other officers of field rank, on 4th May 1963. We reached Barrackpore, the Military Airport at Calcutta at mid-day but could not land there and were diverted to Dum Dum.

We deplaned and were greeted with correct military protocol, tinged with a chill reserve.

It was only later that I found out that we had to clear ourselves of the charge of having been brainwashed — a strange charge from a Government which had itself been brainwashed into championing China’s cause for more than a decade without a doubt the prisoners had been declared outcasts.

Apparently we should have atoned for the past national sins of omission and commission with our lives.

Our repatriation was embarrassing as the national spotlight had again been focused on the Sino-Indian Conflict.

From the tarmac we were herded straight to the Customs enclosure where a sprightly team of appraisers had assembled to ‘examine’ our luggage.

They had been told that some Indians had arrived from Hong Kong and were waiting to confiscate transistors and opium! I knew then that there had been no material change in India and we were in the same old groove.

After a cursory and stereotyped de-briefing at Ranchi, I was ordered to meet the Chief of Army Staff, Gen. J.N. Chaudhuri at Delhi on 15th May.

He asked me to write a report for the personal information of the Defence Minister and himself.

The aim was, in Gen. Chaudhuri’s words: “To teach ourselves how not to hand over a brigade on a plate to the Chinese in future”.

He added that we had become the laughing stock of even countries like… and … (I hesitate to name these countries!).

I welcomed the opportunity afforded by the Chief’s instruction for a personal report as this would give me a chance to collect my thoughts.

The basic facts had been branded into my memory. To make doubly sure, I had many sessions with Lt. Col. Rikh, Commanding Officer of 2 Rajputs and Lt. Col. B. S. Ahluwalia, Commanding Officer of the 1/9 Gorkhas, Major R.O. Kharbanda and Captain T. K. Gupta of my Staff.

We recounted, cross-checked and authenticated the facts which form the basis for this book.

Rankling at our unfriendly reception and the many garbled versions I heard from friends, I wrote a forthright account which 1 handed over to the Chief personally.

I do not know the fate of this report as I was never again asked to discuss or explain it. It may have touched some sensitive nerves.

It was soon apparent that the Army had become the centre of much controversy and that the blame for the 1962 fiasco had been cunningly shifted to its alleged ‘shortcomings’.

What was more alarming were the extravagant claims made by some senior Army Officers, who attained eminence only after the 1962 reshuffles, as to how brilliantly they would have handled the situation and defied the authority of Nehru, Menon and Kaul.

This attitude made me despair of whether my countrymen and colleagues would ever learn any lessons from India’s first attempt at conducting a modern war and strengthened my resolution to tell my story.

1962 was a National Failure of which every Indian is guilty. It was a failure in the Higher Direction of War, a failure of the Opposition, a failure of the General Staff (myself included); it was a failure of Responsible Public Opinion and the Press. For the Government of India, it was a Himalayan Blunder at all levels.

The people of India want to know the truth but have been denied it on the dubious grounds of national security.

The result has been an unhealthy amalgam of innuendo, mythology, conjecture, outright calumny and sustained efforts to confuse and conceal the truth.

Even the truncated ‘NEFA’ Enquiry has been withheld except for a few paraphrased extracts read out to the Lok Sabha on 2nd September 1963.

For some undisclosed reason, I was not asked to give evidence before this body nor (to the best of my knowledge) were my repatriated Commanding Officers.

It is thus vitally necessary to trace, without rancor and without malice, the overall causes which resulted in the reverses and which so seriously affected India’s honour.

Some of the things that happened in 1962 must never be allowed to happen again.

There is a school of thought which advocates a moratorium on the NEFA Affair on the grounds that such ‘patriotic reticence’ is desirable in the context of the continuing Chinese (and Pakistani) military threats. I do not think that this theory is tenable.

The main protagonists of this line played a part in the tragic drama, or belonged to the political party which provided the national leadership and their plea for silence does not spring entirely from a sense of patriotism.

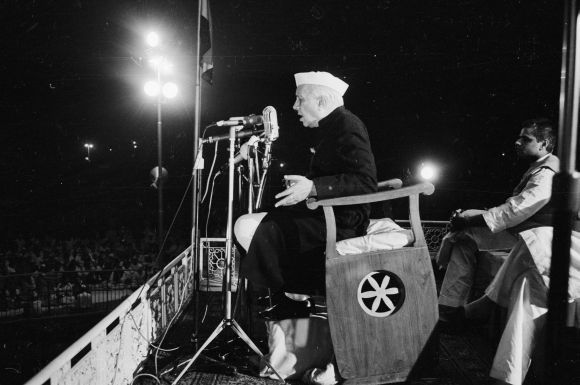

There are others, mostly barren politicians, who use the Nehru legend to buttress their failures, or inveterate hero-worshippers who express irritation at any adverse reference to Mr Nehru’s long spell as the Prime Minister of India.

As was said of Lord Chatham, the British Prime Minister, ‘His country men were so conscious of what they owed him that they did not want to hear about his faults’.

But it is impossible to narrate a failure, which historically marked the end of the Nehru saga, without critical, often harsh comments on the principle dramatis personae who held high office and who were revered by the people.

The magnitude of our defeat could not have been wrought without Himalayan Blunders at all levels. But this is not a “J’accuse”.

India has a near unbroken record of military failures through the ages. Our peasantry has always fought gallantly; but it is an indisputable fact that seldom has this bravery been utilised to win battle field victories and thus to attain our political objectives, due to inept political or military leadership, or both. Need we follow this tragic path interminably?

It had fallen to my lot to be associated with the China problem for over 8 years from 1954 to 1962.

I was first connected with the Higher Direction of War, in a modest capacity, as a Lt.-Colonel in Military Operations Directorate.

Later, as Brigadier-in-Charge of Administration of the troops on Ladakh, I saw, at first hand, what passed for ‘logistic support’.

Finally as Commander of the key sector of Towang, North-East Frontier Agency, I was involved in our so-called operation al planning to defend our borders.

The years of higher responsibility were complementary and gave me a personal insight into our National Policy as well as our half-hearted military response to the Chinese challenge.

I have tried to tell the story as I saw it unfold, over the years, to add to our knowledge. I have included the politico-military background only because this had a direct bearing on our performance in the military field, in 1962.

This is a personal narrative — a narrative of what 7 Infantry Brigade was ordered to do and what happened when they attempted to carry out those orders.

In all humility I can claim that only I am in a position to explain many nagging questions that need explaining, facts that are necessary.

The theme of the book is the steadfastness of the Indian soldier in the midst of political wavering and a military leadership which was influenced more by political than military considerations.

The book records their valour, resolution and loyalty – qualities which are generally forgotten in the mass of political post-mortems which have been served up to the Indian people.

This is a record of the destruction of a Brigade without a formal declaration of war — another central fact that is often overlooked — and which coloured the actions of all the principal participants.

I have made every effort not to view things in a retrospective light or with the clarity of hindsight. I have recorded experiences, ideas and feelings as they appeared at the time.

I have tried to give an objective account of all that happened, of the people involved and of the decisions they took.

My opinions as a participant in the climatic finale of September-October 1962 must be subjective. The main essential is to know how the principal participants thought and reacted.

As Lord Avon (Sir Anthony Eden) says in the preface to his Memoirs, The Full Circle: “This book will expose many wounds; by doing so it may help to heal them”.

By this book I express my undying gratitude to my Commanding Officers for their trust and loyalty; to the men of all classes and from all units under my command for their selfless devotion to duty; and to my staff whose dedication sustained me in those harrowing days.

This book is the fulfilment of my promises to my friends, in all walks of life, to vindicate the reputation of the men I had the honour to commando I hope that I shall have discharged my responsibility to all those who gave their lives in the line of duty and whose sacrifice deserves a permanent, printed memorial.’

Claude Arpi is a regular contributor to Rediff.com.

Feature Production: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

- Remembering A War

Source: Read Full Article