‘Gerson existed at the intersection of principle and conscience.

‘One of our conversations turned to his return to India from Brazil.

‘He spoke about the choices he made and the things he felt he had failed at.

‘What emerged was how he always steadfastly stuck to his beliefs and was true to them and himself.

‘The need to — in Spike Lee’s words — Do The Right Thing.’

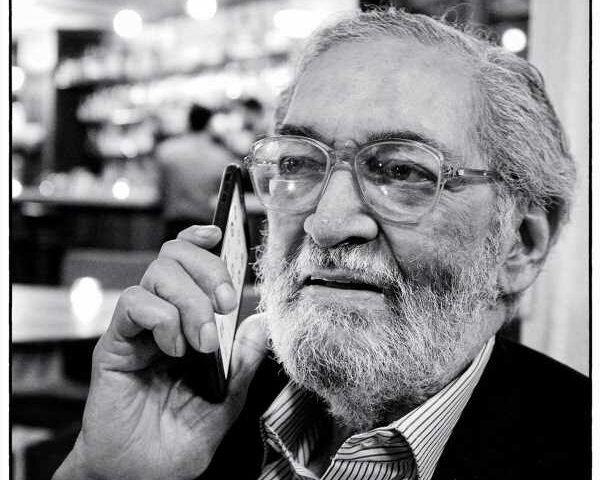

Director Dev Benegal remembers Gerson da Cunha, ‘friend, guide, light’.

The geography of grief has no boundaries.

Uma da Cunha’s first words to me were, “Why aren’t you here to hold my hand?”

I was twelve thousand kilometers away. All of us wanted Gerson to live forever.

Uma and Gerson were the first people I met when I moved to Bombay in 1979.

He was a friend of my father’s, while Uma and my mother had both studied at Miranda House in Delhi.

His life and my father’s had similar parallels — All India Radio, journalism, advertising, theatre, writing and poetry.

Uma soon became a close colleague. And Gerson became my friend — someone I knew independently of my parents.

From Bombay Wallahs, his poem from So Far: A Collection Of poems:

Nowhere is ever home

but this may be the town

of least effort for me.

Here the idiom is known.

The opening lines became the foundation of the stories in the films I made and wrote, about outsiders trying to make sense of the world they inhabited, constantly searching for that elusive idea we call home.

Agastya Sen in English, August, K.P. in Split Wide Open, Vishnu in Road, Movie, Darnel Temulentum in Dead, End, Nilofer in Further to Fly, and the unnamed assassin of Bombay Samourai, all have that in common.

Gerson attended the premiere of every film I made.

Encouraging me as an emerging film-maker and in the later years sending me notes about the new films I was writing. Always present as a therapist, for problems I was facing with characters and plots.

While I knew Uma would wave her casting director’s magic wand and find actors who could live my stories, it was for clarity I turned to Gerson.

I would present a specific problem, like a patient might to their doctor: Should the angel be real or imaginary in Further to Fly? Gerson came back with this: “Ambiguity is a great idea in cinema as long as it has clarity.”

Three decades of conversations, correspondence and stories over meals (berry pulao from Britannia restaurant) are hard to compress here.

Gerson was the ultimate raconteur: Subtle, nuanced, bursting with wit, never losing that eagle-eye for detail.

Over a meal I cooked for Uma and Gerson, he told me a story of “a beautiful Swedish woman he met at dinner.”

Gerson meets this woman one evening in Bombay. They decide not to tell each other their names and continue the conversation.

Somewhere along the way she asks him to go to her house and bring back a key lying on her bed beneath her pillow.

He leaves the party and walks to Colaba, past the railway officers’ housing to her building.

He walks up to her apartment, into her room where he finds the key and brings it back to the dinner party. They slowly discover each other and who they were.

His story ended there.

I wanted to make a movie of it.

This was something that Edward Yang might film in Taiwan, Kar-Wai Wong in Hong Kong or Almodovar in Spain. And it happened in Bombay, which to me — the outsider — was the closest in India to a multicultural city.

The “world city by the sea” as Gerson called it.

Gerson taught me the importance of walking the city.

Colaba, Fort, Ballard Pier, Dadar, Mahim, Prabhadevi, Worli, Mahalakshmi, Juhu, Andheri. I walked them all.

I was from Delhi. I fell in love with Bombay.

New York — his other love — is also a city to walk and Gerson loved walking its streets for the social and cultural discovery, the Babel of tongues, the weird mélange of sounds and smells and sights and the light..

It became difficult in the last years. When Uma and I got him a walker to ease the discomfort, he refused to open the box.

Sticking to his cane, he stubbornly insisted on walking on his own, defying the relentless cruelty of time, only occasionally putting his hand out to say “Dear boy, now will you give me a hand?”

Gerson existed at the intersection of principle and conscience.

One of our conversations turned to his return to India from Brazil.

He spoke about the choices he made and the things he felt he had failed at. It was unusually candid.

What emerged was how he always steadfastly stuck to his beliefs and was true to them and himself.

The need to — in Spike Lee’s words — Do The Right Thing.

Bombay, the city, became his passion. And his memory of the Bombay, his understanding of what it represents to its people and to the world, his concern for its citizens triggered Action for Good Governance and Networking in India (AGNI).

Adversity never diminished his sense of humor.

A few weeks ago I was revisiting Manu Chao’s song Homens in Portuguese — a language Gerson spoke with élan — about two women singing about a “real man”.

Porque o verdadeiro homem

Ele te ama, te ama

Te trata, te trata

Com carinho

Com respeito

E amor

E vai te dar por toda vida grandes felicidades

Serão felizes

Esse é o homem de verdade, esse é o homem de verdade

Gerson came to mind immediately. I sent him the song (external link).

He replied:

“dear dev: my computer has been / is misbehaving – before another show of temperament thanks: for remembering brazil and me, for telling us of a possible trip here, for getting in touch at all – I’m as fine as you’d expect a 92-year old to be – but, as God said to moses, “have to pay attention to those tablets. love, gerson”

Gerson did not drink. But he liked to hold a glass and pretend he did — Sprite with Angostura bitters was his thing.

Uma asked me — after apologising for sounding maudlin — “Where do people go when they die?”

The answer is perhaps this: People, especially like Gerson, leave, but they don’t go at all. Like the mountains, they remain.

We will meet again in the hereafter, he and I. We will make a Buñuel Martini (gin, never vodka, stirred, never shaken). Something to look at, value, but never sip.

Adieu, Gerson, friend, guide, light. Your spirit will live forever, in my films and beyond.

Dev Benegal is a film director and writer.

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article