There are several ways in which India’s economic recovery could become even more difficult.

Dear Readers,

As this month draws to a close, the Indian economy is completing the first quarter of the current financial year — April, May and June. Two questions come up in this context:

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

In other words, what is the nature of the current challenges facing the Indian economy and where do the future threats lie?

The end of any quarter typically throws up a lot of economic analysis. Last week, the Reserve Bank of India released its June bulletin, which provided the RBI’s assessment of how the Indian economy is placed.

Even though hardly any entity knows as much about the Indian economy as the RBI, the more instructive analysis was carried out by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (or NCAER) as it released its Quarterly Economic Review.

Let’s first look at the current challenges.

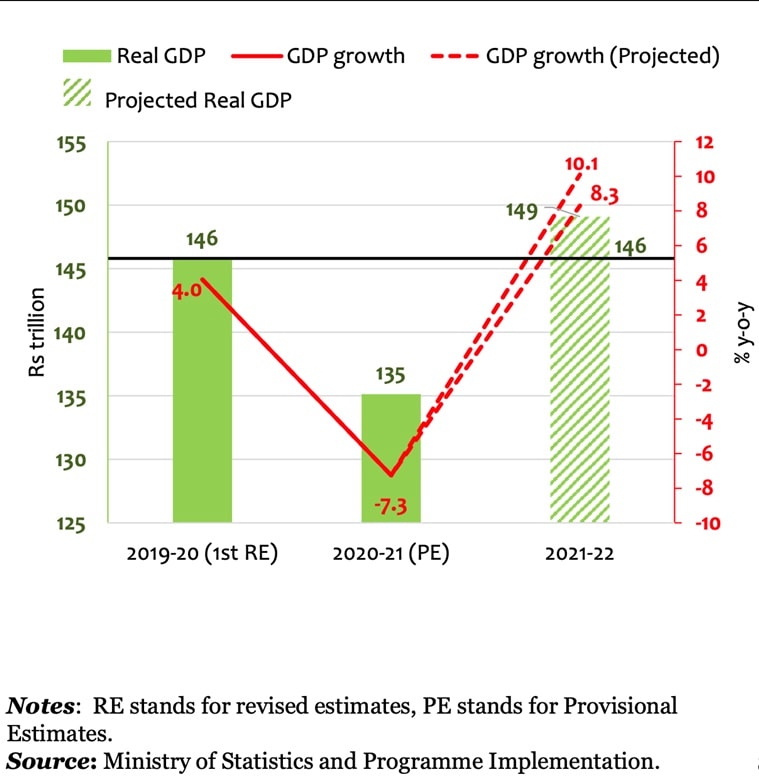

1: Two years worth of GDP growth has been lost

The chart below provides an understanding of how the Indian economy has been hit. First of all, look at the green bars. They show the total amount of India’s GDP as measured in trillions of rupees — the left-hand side scale.

In 2019-20, India’s GDP was Rs 146 trillion. In other words, India had produced goods and services worth Rs 146 trillion that year. Then, in the last financial year — that is, in 2020-21 — it fell to Rs 135 trillion. That’s the fall of minus 7.3% we were talking about earlier.

In the current financial year — that is, in 2021-22 — the GDP is expected to grow back to Rs 146 trillion after registering a growth of 8.3%. This would mean that, in terms of overall economic production, India would have lost two full years of growth. For instance, if there was no Covid disruption and India grew by even 6% in both these years, the total GDP would have reached the level of Rs 164 trillion — that is, Rs 18 trillion more than where India is likely to end up now.

There is a chance that India may grow by 10.1% this year, instead of 8.3%, and in that case, India’s GDP would go up to Rs 149 trillion but even so, India would be far off from where it could have been without Covid.

The red line, which maps the growth rate of GDP in percentage terms (and corresponds to the scale on the right-hand side of the Chart) gives an impression of a “V-shaped” recovery. But, in terms of actual production, the economy will only manage to recover the ground it lost last year.

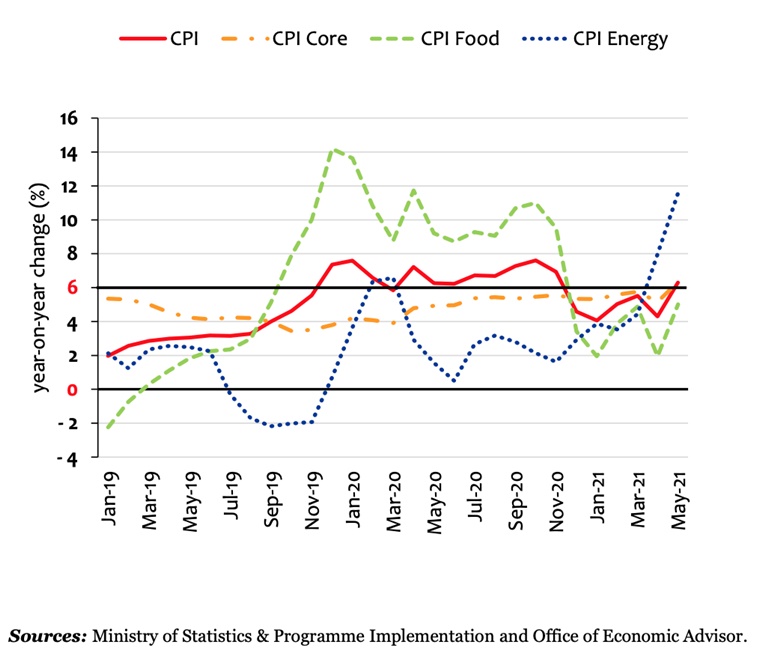

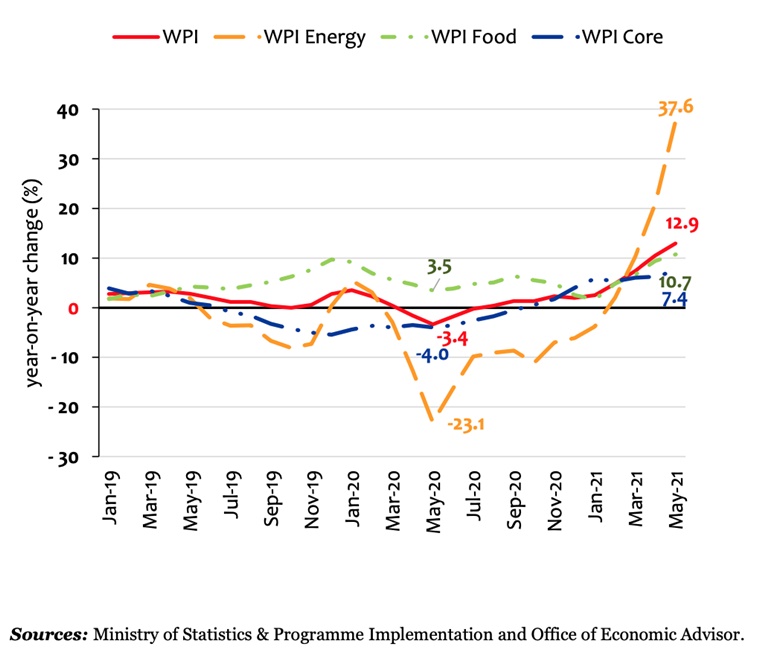

2: Both retail and wholesale inflation is trending up

At a time when economic growth has taken a hit and recovery is muted due to the second Covid wave, India is also facing ever-increasing prices. CHARTS 2 and 3 provide a break up of how retail and wholesale inflation has behaved over the past couple of years.

Headline retail inflation, the read line in CHART 2, is the rate at which prices increase for retail consumers like you. This inflation rate stayed above the RBI’s comfort zone (2% to 6%) between November 2019 and November 2020. But, after a brief period of martial relief, it has again crossed the 6%-mark in May this year.

The other crucial line to look at is the orange dotted line. It shows the core inflation — it is calculated by taking away the price rise in fuel and food items. The fact that even this inflation rate has remained consistently close to RBI’s upper limit, shows that it is not just a matter of petrol and diesel prices being very high or vegetables and fruit prices rising too fast. The common Indian is witnessing a fast rise in prices across the board.

What about wholesale prices? CHART 3 provides the answer. For a long time, the wholesale prices were not increasing too fast. But starting from January onwards, that trend, too, has worsened. In May, WPI inflation was nearly 13%. In other words, wholesale prices were rising at the rate of 13%.

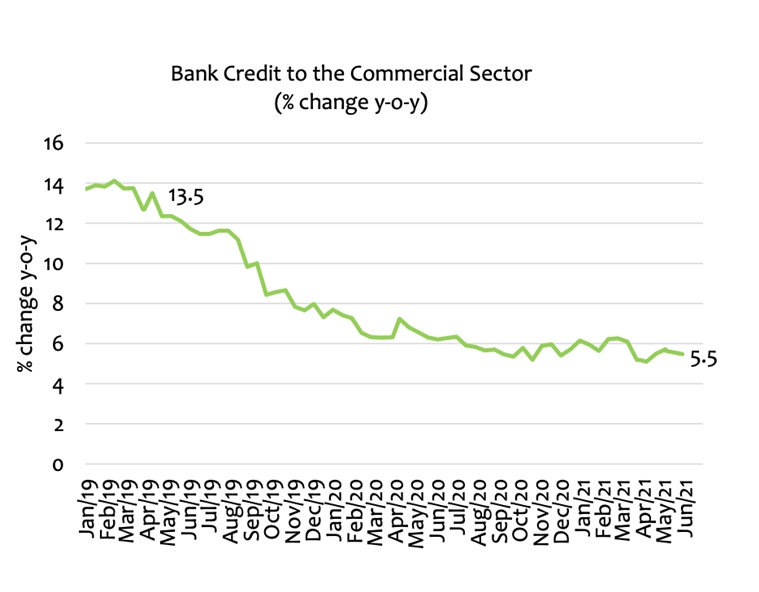

3: Poor credit offtake in the commercial sector

The biggest engine of GDP in the Indian economy is the expenditure that Indians undertake in their private capacity. This demand for goods and services — be it in the form of a new car or a haircut or a new laptop or a family vacation — is what accounts for more than 55% of all GDP in a year.

Even before Covid, the Indian economy had reached a stage where the common man was holding back this expenditure. The first Covid wave made that trend worse with people either losing jobs or salaries being reduced. The second Covid wave has compounded the problem further because now everyone is bothered about the high health expenses.

In the absence of consumer spending, the country’s businessmen — both big and small — are holding back new investments and refusing to seek new loans.

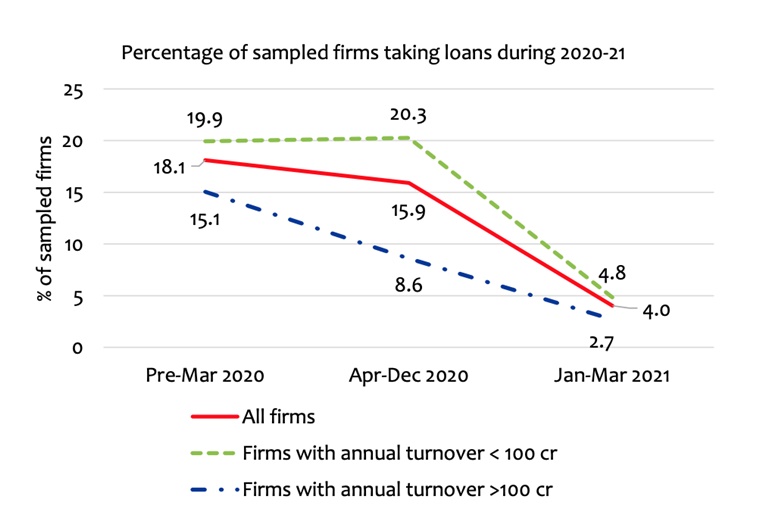

CHARTS 4 shows how bank credit to the commercial sector has plummeted in just the last two years. CHART 5 shows how the percentage of sampled firms seeking loans has just collapsed.

These essentially imply that businesses are not very hopeful of increased demand in the near term.

4: Inadequate spending by the government

Given that domestic consumers are holding back consumption and domestic businesses are holding back investments (the second-biggest engine of GDP growth), it was incumbent on the third-biggest engine of India’s GDP growth — that is, the government — to spend more and pull the economy out of the current rut.

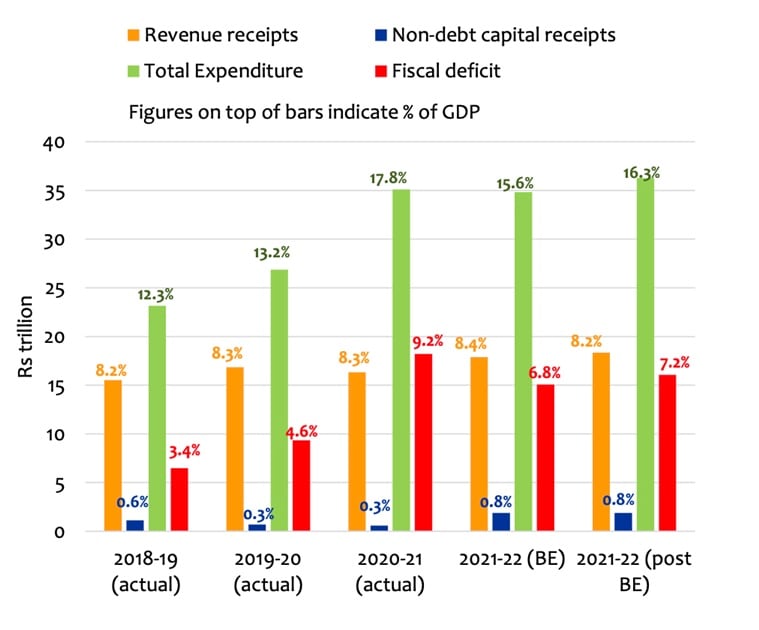

But as the green bars in CHART 6 show, the Indian government has been stingy about spending more. The green bars show the total expenditure (in terms of a per cent of GDP). After being forced to spend more in 2020-21, the government has actually pulled back (as a proportion of GDP) in 2021-22. It is for this reason that its deficit will fall in FY22 as against FY21.

But this move is proving to be counterproductive for India’s economic revival. The NCAER review makes the following remark: “Unfortunately, an inexplicably contractionary fiscal policy in 2021–22, sharply reducing the deficit, will delay recovery.”

What about the future threats?

There are several ways in which India’s economic recovery could become even more difficult.

1: The slow pace of vaccination and a possible third Covid wave

By now it is clear that there is no economic recovery unless India gets a significant majority of its population vaccinated. If the pace of vaccination continues to lag, there is the possibility of a third wave, which may bring with it another round of disruption.

It is also very important to understand that even the possibility of a third wave is quite dangerous for economic recovery. That’s because the increased uncertainty further worsens the trends of consumers holding back consumption and businesses holding back new investments. This is more so because the people’s resilience and ability to deal with the adverse effects of Covid has also been coming down.

2: Monetary policy hitting a barrier

Between fiscal policy (which has to do with government’s spending) and monetary policy (the ease with which one can take a loan and the interest rate one has to pay on new loans), most of the heavy lifting towards achieving economic revival has been done by the RBI. As mentioned earlier, the government has not been expanding its fiscal policy by as much as many expected it to. Indeed, it was largely left for the RBI to pump in loads of cheap money in the form of new loans in a bid to jump-start the economy.

But there are several reasons why RBI may not be able to help out for much longer.

For one, as shown earlier, inflation rates are spiking. The RBI, which is legally required to control inflation, will have to do whatever it takes to keep inflation within bounds. Typically, this would require the RBI to raise interest rates.

There is another reason why RBI might have to raise the domestic interest rate. Thanks to the sharp spurt in economic growth and inflation in the US, its central bank — the Federal Reserve — could soon raise US interest rates. If India has to remain an attractive destination for global investors, RBI would have to give up on the regime of low-interest rates.

3: The long-term adverse effects of short-term shocks

Beyond the above-mentioned threats, and, in fact, regardless of them, NCAER economists such as Sudipto Mundle and Bornali Bhandari point to another key challenge: Hysteresis. In other words, the long term effects of the short term shocks.

“Starting from a 2020–21 baseline which is 7.3 per cent lower than in 2019– 20, GDP has to grow well above the recent pre-pandemic trend rate (5.8 per cent) for India to catch up with its pre-pandemic growth path. This will require deep and wide-ranging structural reforms in the financial sector, power & foreign trade. Reforms in cooperation with the states are also urgent in health, education, labour and land, which are all primarily state subjects,” they wrote as early as December.

While clarifying on this point during the latest quarterly review, Mundle stated: “In fact, the main burden of our song is that the impacts of this [Covid shock] are more long term than one might imagine and by then India would have gone beyond its sweet spot of so-called demographic dividend… so the long term impacts are very very frightening.”

Stay safe,

Udit

Share your comments and queries at [email protected]

Source: Read Full Article