What was the 1987 judgment of the Allahabad HC referred to by the Gujarat High Court Chief Justice? What was the state's position? What were the court’s observations?

Hearing arguments on the preservation of Pratap Vilas Palace in Vadodara, a Gaekwadi heritage structure, the Gujarat High Court Chief Justice recalled a similar judgment by Allahabad High Court cited recently by the advocate general during arguments into the Central Vista redevelopment project in Supreme Court earlier this year.

The petitioners had contented that the proposed railway institute opposite the Pratap Vilas Palace would not only ruin the frontal view of the palace but also lead to cutting down of decades-old trees. The palace houses the National Academy of Indian Railways (NAIR).

During the course of the arguments and discussion, the court was also informed that the decades-old trees serve as lungs of the city and replacing them with new saplings would not serve the same purpose as mature trees do.

It was in this context that Chief Justice Vikram Nath recalled a similar imbroglio in his parent Allahabad High Court more than 35 years ago in Arun Kumar versus Mahanagar Palika, Allahabad and others.

What was the 1987 judgment of the Allahabad HC referred to by the Gujarat High Court Chief Justice?

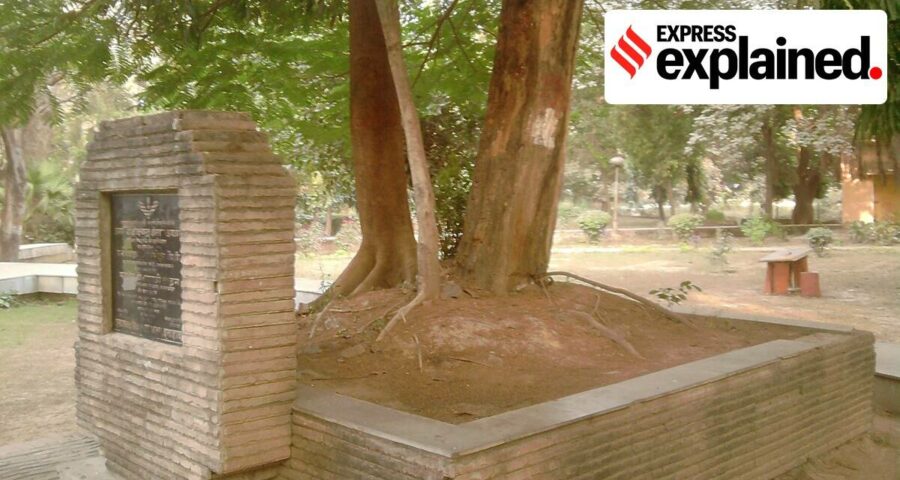

In 1986, a litigation was taken up at the Allahabad High Court, which contested construction plans in the city’s centrally located 133-acre Alfred Park, now called Chandrasekhar Azad Park as it was here that the freedom fighter was shot dead. At the time, it was noted that as per the Allahabad Master Plan of 1975-91, prepared by the Uttar Pradesh government town planning department, a number of important community buildings such as a stadium, a museum and a public library were already located in the park.

In the winter of 1986–87 a resident of 121 Tagore Town, Allahabad moved the high court complaining on south of the park, walls were being raised and a building was being built away from public view. This building was being constructed next to another building which had been completed recently and not yet occupied. He complained that this building activity was illegal, against the law which controls urban planning and open spaces and that there is nothing left of the park. He sought a stay on construction and an injunction to prevent occupation of the other recently-constructed structure. The court granted an interim order favoouring the petitioner, but the same was violated as construction activity continued. Kumar then sought that the two new buildings be demolished and any further encroachment of the park be prevented. It was also sought that the identity of the park be restored.

Who were the other parties?

Among those who joined the litigation at this point was a set of 16 students of the University of Allahabad who stayed at the Madan Mohan Malaviya University Hostel directly opposite the north-west corner of Alfred Park. The students contended that they use the park in the mornings and evenings for their physical exercises as well as studying. However, the students submitted that if indeed buildings have to be constructed then a hostel for the students of the University of Allahabad should be erected inside the park as well.

Another set of nine intervenors supported the government’s cause of keeping the buildings and going ahead with further construction, but had little to add on the legality or illegality of the structures.

What was the state’s position?

Government of Uttar Pradesh had submitted that the park was not a public park but a horticulture garden and thus Arun Kumar or the other intervenors had no locus standi in the matter. Secondly, the state said it had the “sole discretion” to do what it liked with the gardens maintained by it, which also included the grant of permission to build in the park. It was also argued that the constructions had already been made and some are in the process of being made and lot of money had been spent. However, the state did admit that it was indeed “incorrect and irregular for the State to have permitted the encroachments of the park when buildings were constructed upon it whether by the State Government or those who had received permission to construct buildings.” The state also did not deny that over the years, the area of the park as it originally stood for use by the public has reduced.

What did the Allahabad High Court do?

Following discrepancies in submissions by different authorities, the court commissioned an architect and surveyor to report on the area of the park and the parts occupied by the buildings to judge how much of the park has been rendered unusable. The court also inquired from the state on how buildings had been permitted inside a public park and “multifarious activities not connected with the park had been permitted to mushroom within its precincts.” The court relied on historical documents dating as far back as 1884 to establish that Alfred Park has indeed always been a public park.

What were the court’s observations?

The court observed, “What has happened to the Alfred Park, is a tragedy which is happening virtually in most of the parks of the city. Open spaces are disappearing and more often than not been occupied by State agencies ostensibly for a public purpose but in a style of bad planning and illegal occupation. Parks reserved for little children have been scarred…What do the children do? Where do they go when they yearn for their parks? Where do they play? In fact, if there ever was, they are the most privileged class and a park is their basic need, whether ward of a poor man or rich man.” It added that the district administration had indeed “mutilated” the park.

Justice Ravi Dhawan’s judgment of April 1987 also observed that Alfred Park’s “open spaces have been abused.”

“The institutions which have been permitted to encroach may be meaningful and with purpose, but there was no occasion to put them in a park. After all, this is what urban planning is all about,” it states, while observing that urban planning is meant for the better enjoyment of a city and public places like public streets and parks are inviolate and are to be protected for the purpose for which they are dedicated.

The judgment further noted, “Much of the illegalities in violating the basic structure of the park have already been committed. It does not take any time to destroy a park and render it useless from being used as a park depriving the residents, whether children, pensioners or citizens looking for an open space. Remedying a wrong situation, in reference, to urban planning may take more than a generation and even then the original concept for which the park was laid out or open space dedicated may not be restored. This is the tragedy of the Alfred Park. Within a span of one generation an open space of 132 acres has been rendered useless as a park.”

The court held that denying citizens the use of the area of the park is illegal.

What did the court rule?

With respect to the two buildings, the court held them to be illegalities that requires to be dismantled. The judgment notes, “Court cannot grant permission to the State respondents to complete these constructions. It must be dismantled. The disfigurement of the park must cease and its open spaces be preserved… These constructions are to be dismantled forthwith. They ought not to have continued in any case…”

The two buildings, one under construction and another already constructed, were directed to be dismantled within a period of six months. Once dismantled, it was directed that the open spaces created in the two plots, will be restored to the public in conformity with the purpose of the park, with one of the area dedicated for “the use of little children.”

The court also advised the state government to relieve the occupancy of another building, which was let out to the Sales Tax department. Instead, the court suggested, may be used by the Horticulture Department.

The court also directed that a stadium situated inside the park be shifted to an alternate site within a period of two years, and once finalised, the new stadium complex should begin to rise in another three years. Once the new stadium is ready, the one inside the park premises must be dismantled.

What is the status of the case?

The Uttar Pradesh government subsequently challenged the Allahabad HC judgment before the Supreme Court where apex court directed the Allahabad HC in 1991 to “hear all the parties” and “try to solve the problem regarding the shifting of the stadium and other problems in a fitting manner after taking suggestions, if any, given by the parties as well as by the State Government.”

The same was done and the Allahabad HC held that there has been clear violation of the provisions of the Uttar Pradesh Parks, Playgrounds and Open Spaces (Preservation and Regulation) Act, 1975 and the Uttar Pradesh Urban Planning and Development Act, 1973 and directed for cancellation of lease for several pre-existing buildings. The HC’s ruling was again challenged by the aggrieved parties, that is proprietors of buildings that had been running from inside the park since decades, before the SC.

This time, the apex court held that the “High Court was not justified in directing cancellation of lease.” The SC held in March 2007 that the two Acts which the said buildings were constructed in violation, cannot apply retrospectively, and thus if on the date of commencement of the Act a park, playground or open space was being used for a particular purpose, the same can be continued.

This essentially meant that buildings constructed inside the park after 1973 and 1975 can essentially be scrutinised while those such as the stadium, ladies’ club etc would remain protected if leases were valid and provided by the competent authority at the given point of time.

Source: Read Full Article