While countries at climate meetings regularly commit to collective action, few have been meeting their targets. These targets are not binding, and developing countries will require much more funding.

The annual climate meetings have succeeded in galvanising the world into taking collective action against climate change, but they have not been able to prevent the crisis from worsening in the last two decades. The quantum of action that these series of meetings has enabled has always been well short of what, science says, is required to avoid the catastrophic impacts of climate change.

Countries have missed their targets, reneged on promises made, and delayed their actions. The decision-making at these meetings has not always been guided purely by climate change considerations. Very often, economic and foreign policy imperatives have over-ridden environmental concerns.

As a result, the world seems to have got locked in a perennial firefighting mode, struggling to cope with the ever-increasing frequency of extreme weather events, which are a direct consequence of global warming.

Missed chances

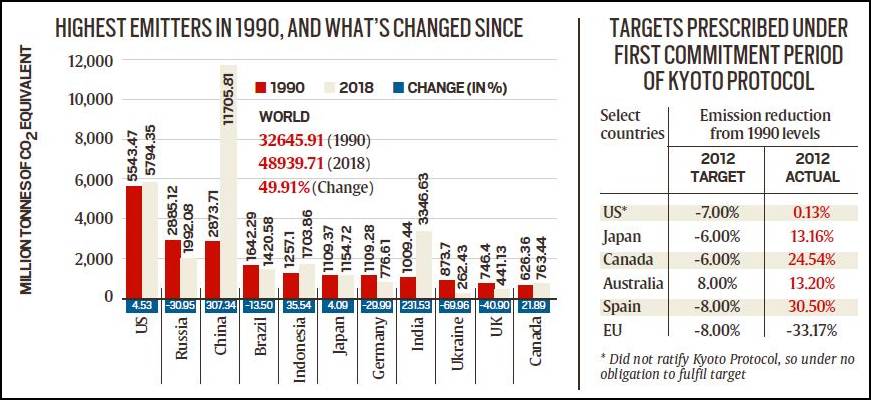

An international agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions was finalised at just the third climate change conference, in Kyoto in 1997, but it couldn’t be operationalised until 2005 in the absence of the requisite number of ratifications. The United States, the world’s largest emitter at that time, did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol and was thus not bound by it.

The Kyoto Protocol asked a group of 37 rich and industrialised countries to collectively achieve a modest 5 per cent reduction in their emissions from 1990 levels during the ‘first commitment period’ of 2008-2012. Except the European Union, and some of its individual member countries such as Germany and the United Kingdom (which was then in the EU), most of the countries did not achieve the target.

Russia and the east European economies, however, saw a dramatic drop in their emissions after the collapse of the Soviet era. It helped a great deal in ensuring that the collective emissions of this group of countries fell by 22 per cent, well above the 5-per-cent target.

Data from the World Resources Institute show that the emissions of the US in 2012 were marginally higher than they were in 1990, meaning there was no reduction. Australia’s emissions went up by about 15 per cent.

Global emissions went up by 40 per cent between 1990 and 2012, thanks mainly to the rapid rise of China and India, which continues to this day. China overtook the United States as the world’s leading emitter around 2007. Its current emissions are more than 4 times the 1990 levels. India’s emissions have grown over 3.5 times from 1990.

Newly growing economies

But countries such as China, India and similar fast-growing economies such as Brazil, South Africa or Indonesia, were not mandated to cut down their emissions, because of well-justified reasons. Over 90 per cent of the accumulated greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the reason for global warming, had come from the rich and industrialised countries over the last 150 years. Countries such as India and China had begun to develop only in the 1980s and 1990s, and needed the space to grow their economies in order make the lives of their people better. This is what gave rise to the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC), the most endearing and empowering provision for the developing countries. 📣 Express Explained is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@ieexplained) and stay updated with the latest

But while they had little contribution in the “historical emissions”, industrial activity in China, India and other major developing countries was leading to their emissions growing at a very fast pace. That was a major grouse for the developed countries, which felt that a free pass to these countries was also handing them an unfair economic advantage at their cost.

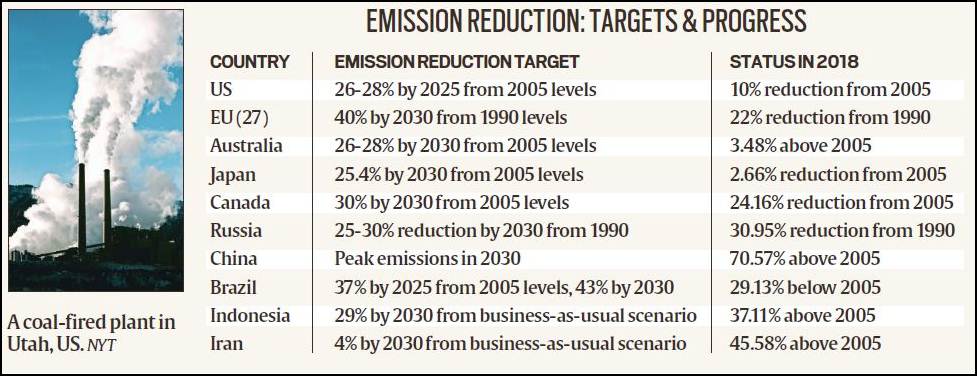

Thus began a systematic effort to erode the Kyoto Protocol and replace it with an architecture that put some constraints on the emissions of India and China as well. It was achieved with the finalisation of the Paris Agreement in 2015 and the formal demise of the Kyoto Protocol last year. In the process, the basic framework of the climate change architecture was severely diluted.

Instead of science-based emission-reduction targets, that were binding in nature, countries were only asked to do what they thought they were best capable of. There is little incentive, and no obligation, for countries to put their best foot forward in a system like this.

Lack of money, tech

More than the lack of adequate action on emission reductions, the developed countries have been found wanting in their commitment to help and support developing countries, especially the least developed ones, in dealing with the impacts of climate change. This included providing money and technology to facilitate adaptation to the changing environment, something that the developed countries are mandated to do, not just under the Kyoto Protocol but also in the successor Paris Agreement regime.

But hardly any meaningful amount of money, or transfer of technology, took place under the Kyoto Protocol. In 2009, at the Copenhagen conference, the then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced that the developed countries would ‘mobilise’ $100 billion in “new and additional” climate finance for developing countries every year from 2020. This promise got written in the Paris Agreement as well.

While the developed countries claim that this sum has already started flowing, developing countries say there is very little money on offer, and that a lot of what is being dressed as climate finance is actually pre-existing aid or money flowing for other purposes. Besides, $100 billion now seems like a paltry amount when estimates suggest that trillions of dollars are required in climate finance every year.

Source: Read Full Article