The surge in female labour force participation rate, as evidenced in the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data for July 2019-June 2020, can be interpreted as a positive sign, but there is a catch: much of this increase is in the most sub-optimal category of unpaid family workers.

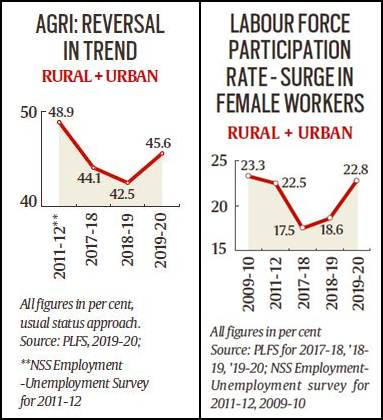

TWO SPECIFIC trends in the Government’s 2019-20 employment statistics, mapped till the first three months of the pandemic (April-June 2020), signify a break from the steady structural transformation in the labour market over the last two decades: reversal of the falling share of agriculture and a decisive turnaround in declining female participation.

Both these trends clearly point to household distress precipitated by the steady fall in GDP growth rates over the past years, say analysts. A Union Labour Ministry official, however, attributed the farm labour surge to a “hard lockdown” in urban areas during April-June, and described the rebound in female participation as a “positive sign”.

The surge in female labour force participation rate, as evidenced in the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data for July 2019-June 2020, can be interpreted as a positive sign, but there is a catch: much of this increase is in the most sub-optimal category of unpaid family workers. The rise in agriculture, too, is mostly in this category — those working in household enterprises without drawing wages.

In agriculture, which constitutes about 16 per cent of the GDP, the PLFS data show that in 2019-20, there has been an increase in percentage terms of those reported to be working in the sector (45.6 per cent, see chart). This comes after decades of a progressive fall that signalled movement to high productivity jobs outside.

At the same time, the surge for 2019-20 corresponds to a decline in manufacturing and construction in the latest survey.

These figures are based on the “usual principal status” and the “subsidiary status” approach in which data is obtained for those who worked or were available for work for a relatively long part of the 365 days preceding the date of survey — and those from the remaining population who had worked at least for 30 days during the same reference period.

The findings are more stark for the “current weekly status” for which the reference period is of the seven days preceding the date of survey. The weekly approach is closer to the global norm, and captures unemployment over a shorter term while the longer-term “usual status” tends to include chronic unemployment and seasonal work patterns.

However, PLFS data for 2019-20 also show that the employment rate for unpaid workers in household enterprises in rural and urban areas increased to 15.9 per cent from 13.3 per cent in 2018-19. For female workers, it increased to 35 per cent in 2019-20 (for rural and urban areas) from 30.9 per cent in 2018-19.

India had recorded a steady decline in employment in the agricultural sector corresponding to the share of output over the years, as is the case for most major developing nations — a trend that has now been reversed.

“There has been an increase in the share of employment in agriculture in 2019-20 even as the share of agriculture in GDP has declined. Lot of people lost jobs during the pandemic and agriculture became the employment of last resort. The distress, however, was brewing before the pandemic struck. GDP had slowed down, demand had declined and manufacturing was not expanding. Between 2004-05 to 2011-12, many exited agriculture to join the construction sector with a big push to infrastructure,” Radhicka Kapoor, Fellow at Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), said.

“Rural India was doing well, but after 2011-12, problems surfaced such as the twin balance sheet problem and rural growth story started petering out. With the inability of the construction sector to absorb those who were exiting agriculture and with the manufacturing sector not taking off, workers got pushed back into agriculture,” Kapoor said.

In the case of women, the PLFS data for 2019-20 show a sharper rise in the participation rate, particularly in rural areas. But worryingly, much of this is again in the category of unpaid family workers.

For instance, the overall female participation rate increased to 22.8 per cent in 2019-20 from 18.6 per cent in 2018-19. In urban areas, the rate increased to 18.5 per cent in 2019-20 from 16.1 per cent in 2018-19, and in rural areas, more sharply to 24.7 per cent in 2019-20 from 19.7 per cent in 2018-19.

Correspondingly, though, the rate of females employed as unpaid workers in households increased to 11.1 per cent (in 2019-20) from 9.6 per cent (2018-19) in urban areas and to 42.3 per cent from 37.9 per cent in rural areas.

“If you look at the details, you find that this increase is not in good quality work but in the unpaid family work category or in the unorganised sector. This is not something to be happy about,” P C Mohanan, former acting head, National Statistical Commission, said.

The two trends, Mohanan said, cannot be viewed as good in terms of gender empowerment. “After demonetisation, there was a slump in employment for all categories and the unemployment rate was very high. Things were recovering slowly up to the end of 2019, but then suddenly a pandemic came in and everything got reversed. After the pandemic, it appears women workers are more affected because of the restrictions such as for public transport,” Mohanan said.

New research by Ashwini Deshpande and Jitendra Singh of Ashoka University suggests that frequent transitions, as well as fall in participation rate, are “consistent with the demand-side constraints, viz., that women’s participation is falling due unavailability of steady gainful employment”.

Using 12 rounds of a high frequency household panel survey, they assert that women are likely to be displaced from employment by male workers, especially when there are negative economic shocks such as demonetisation or the pandemic. This trend had intensified, as corroborated by CMIE data for months beyond July 2020.

“Industries that employ women haven’t done well. Unlike Bangladesh, we did not have labour intensive manufacturing. Even though rising education levels have been seen among females, there aren’t enough good jobs for them,” Kapoor said.

The updated CMIE’s Pyramid Household Surveys for months subsequent to July 2020 show a loss of employment in service and manufacturing sectors that seems to be accompanied by a progressive shift towards low-paying subsistence work.

Source: Read Full Article