In region that carries Partition scars, no one denies BJP has done work — or that social fissures now run deeper due to its Miya rhetoric.

“SCHEMES for women, free ration during lockdown, new roads… there is no reason to complain about the last five years. Zero,” declares Manoj Nath, who owns a fruit shop in Katigorah in Assam’s Cachar district. A few metres away, selling gift items at his shop, Shahin Ahmed Chowdry says, “Yes, roads were built, but…none of the schemes reached me.” Dropping his voice, he adds, “They can build all the roads in the world but then they are spreading hate.”

Close by, in Cheragi Bazaar, near the border with Bangladesh, Hanif Alam, who sells electronic goods, agrees. “They made a law like the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), which is fine. But why leave out Muslims?”

In 2016, both Chowdry and Alam had voted for the BJP. “And what change did they bring?” says Alam. “Every other day, I see videos of someone being forced to say ‘Jai Shri Ram’ or being lynched. At least, before this our country was peaceful.”

Unlike the linguistic, ethnic lines cleaving the rest of Assam, in Barak Valley, religious affiliation is an overriding factor. Much of the valley’s memories are shaped by Partition — when a large part of Assam’s Bengali-speaking Sylhet was made part of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), while one part (Karimganj) was included in Cachar district, without any affinity to the region. Consequently, there was large-scale migration of Bengali Hindus to Barak Valley, and now Hindus and Muslims are evenly matched in numbers.

Barak Valley’s ties with the BJP, in fact, go back as early as the 1990s.

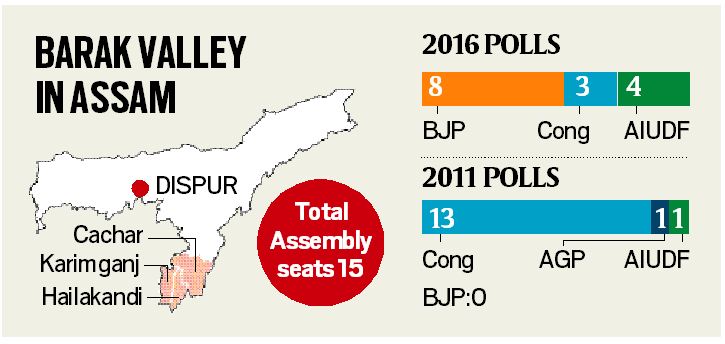

First its CAA promise, excluding Muslim immigrants, and now its rhetoric targeting ‘Miya’ culture are playing on the intrinsic divide in Barak Valley. Its 15 Assembly seats (seven in Cachar district, three in Hailakandi and five in Karimganj) vote on April 1.

On Tuesday, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi released a video message for Assam, reiterating they would not allow the CAA.

Attributing the CAA delay to Covid, Rajdeep Roy, Silchar MP and Assam BJP general secretary, says, “The CAA has been passed by Parliament. It has gone through checks and balances, how can it be divisive?”

For Satish Das, a rickshaw-puller who lives in a Hindu settlement in Silchar, 2019 was a blur of trips to Guwahati and a loan of Rs 20,000. “Still my daughter’s name did not make it to the NRC,” he says, hardly reassured by neighbours telling him that the “Hindu law” will protect her.

However, on April 1, Das will vote for the BJP. “I have heard on TV that the BJP runs the desh (country) well,” he says.

In Udharbond, Mompi Dey is as forgiving despite not getting “even ek mutthi (a fistful)” of free rice during lockdown. “It’s not the BJP or PM Modi’s fault,” she says. Plus, her husband adds, at least they are not siding with an “anti-Hindu” like Badruddin Ajmal.

While the AIUDF has always had a presence in Barak Valley, the BJP’s vilification has turned Hindus against it, as well as ally Congress. “I worry that Ajmal may become Chief Minister,” says Pushpa Dey, in a Silchar market.

But simple mathematics may work against the BJP, says Joynal Abedin, professor at Nabinchandra College in Karimganj, with Congress and AIUDF votes consolidating in Hailakandi and Karimganj, which are Muslim majority.

Abedin adds that it is clear the BJP has done work. The Modi government brought a broad gauge railway line to Barak Valley, roads and a much-needed passport office. “Even Muslims developed a soft corner for the BJP,” says Abedin. “But they say ‘don’t want Miya votes’, call us Mughals.”

Urban Silchar has seen many minor communal clashes in recent years. Mizajul Rahmen, who runs a tile business in the city, points out that his best friends are Hindus. “How are we outsiders?” he says. “It is the Hindus who came here. We were here from before.”

Source: Read Full Article