As we approach the 20-year anniversary of 9/11, it is worth examining whether the War on Terror served its purpose and assessing the cost at which it came for American citizens

The September 11 attacks were a devastating blow to US national identity, threatening the public’s sense of safety and putting into doubt the very notion of American exceptionalism. After 9/11, policymakers sprang into action and introduced the Authorisation of Use of Military Force (AUMF,) a sweeping piece of legislation that sanctioned the use of US military services against those responsible for the attacks. Out of 500 Congressmen and women, only ONE voted against the AUMF. When asked to justify her vote, that lone Congresswoman, Barbara Lee, quoted her preacher, saying, “as we act, let us not be the evil we deplore.”

Lee’s words seem prescient in hindsight but at the time, they were in stark contrast to the fervour of nationalist rhetoric that had engulfed the country. In a USA Today poll conducted five days after the attacks, 49 per cent of Americans indicated that they would want Arabs and Arab-Americans to carry some sort of special identification and 58 per cent said they would like to see those groups be subject to additional screening before boarding a flight. The threat of terror that had once only existed outside of its borders, was now beginning to permeate every aspect of US life.

Terrified by the prospect of further attacks, the American public overwhelmingly supported the War on Terror, defined by President Bush, according to an essay by Ben Rhodes, the US Deputy National Security Advisor during the Obama administration, as “a defining, multigenerational and global war” on par with the “epochal struggles against fascism and communism”. The subsequent “jingoism of the post 9/11 era” according to Rhodes, “fused national security and identity politics, distorting ideas of what it means to be an American and blurring the distinction between critics and enemies”.

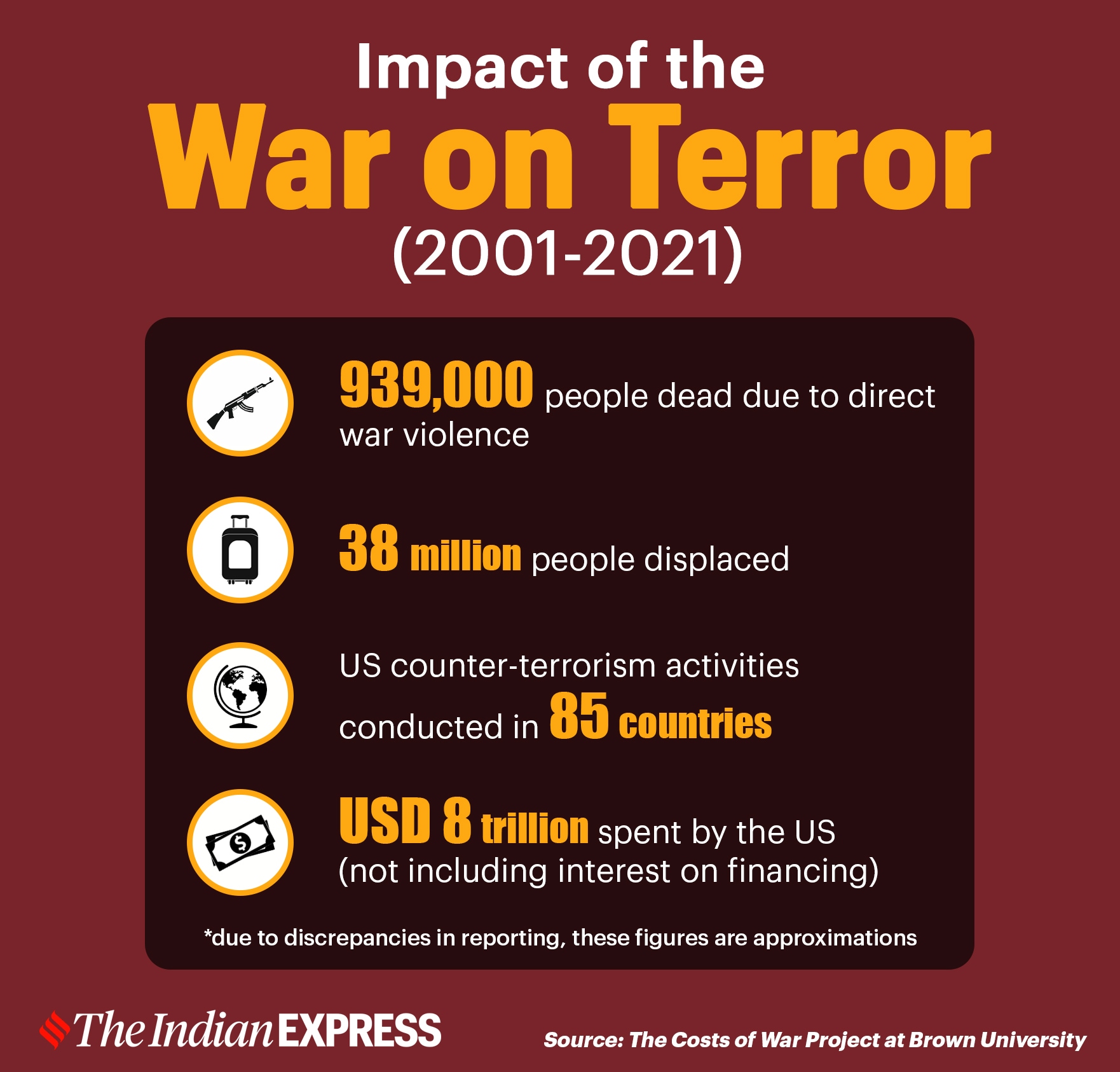

After the attacks, counterterrorism and the politics of fear dominated American political discourse and moulded US National Security policy. As we approach the 20-year anniversary of 9/11, it is worth examining whether the War on Terror served its purpose and assessing the cost at which it came for American citizens.

Domestic and Foreign Policy

During his first presidential election campaign, George Bush strongly opposed the concept of nation building. However, after 9/11, the US view of the post-Cold War order changed significantly. According to Thomas Hegghammer, a Senior Research Fellow at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, who spoke with indianexpress.com, “it was impossible for a country like the US to be attacked and not respond, the public sentiment demanded some sort of action”. After Bush launched the War on Terror, the speed and scale of US counterterrorism efforts in the early years was remarkable. In addition to the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, that characterised the War, the US also led counterterrorism initiatives in 85 countries, training and equipping foreign governments to curtail regional terror threats.

The US foreign policy after 9/11 was a mixed bag. On one hand, Bush had to respond in the wake of the largest attack witnessed on US soil, but on the other, the proportionality of the response was overblown. According to Hegghammer, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were largely retaliatory and overdrawn, coming at a great cost to civilian lives. “Instead of investing so much manpower, time and resources into policing Afghanistan and Iraq on the ground, the US could have maintained a light aerial presence and focused on technological methods of identifying terrorist cells,” he says. In an essay for Foreign Affairs Magazine, Elliot Ackerman, an author, and former US marine, further separates the need to respond to 9/11 from the need to conduct whole-scale invasions, stating in reference to Afghanistan and Iraq, that “the long, costly counterinsurgency campaigns that followed in each country were wars of choice”.

Domestically as well, Bush made radical policy and governance changes following the 9/11 attacks. In addition to the passage of the AUMF which gives the President the unparalleled abilities to wage and declare wars, the US Congress also authorised the passing of the Patriot Act, reorganised 22 Federal Agencies, created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and extended the scope of the National Security Agency (NSA.)

Once again, some of these changes were necessary in light of the new threat of asymmetrical warfare. However, legislators, unwilling to be seen as undermining national security, allowed the federal government to operate without proper congressional oversight. Consequently, the US government was able to abuse these powers of surveillance, detention, and interrogation.

Patrick Toomey, a Senior Staff Attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union, tells indianexpress.com that in order to justify these actions, the US government “created a false choice between security and privacy” opting for mass surveillance programmes even when agencies had “far more targeted” tools to obtain the information they needed.

Was the War on Terror successful?

Putting aside its eventual overreach, in terms of its original objective, to eliminate the global threat of terrorism, the War on Terror has been a relative success. Although there have been large-scale attacks on Western countries such as the bombing of a train station in Madrid in 2004, the attack in Paris in 2015 and the assault on a nightclub in Orlando, Florida in 2015, the threat of Islamic terrorism to Americans is relatively low today. According to the New America Foundation, since 9/11, the US has suffered, on average, six deaths per year due to jihadi terrorism. Additionally, none of the attacks that occurred on Western soil were from locally based organisations and none of the perpetrators were able to strike more than once.

The US invasion of Afghanistan largely neutralised the threat of Al Qaeda and although the Taliban have come back to power, as pointed out by Hegghammer, the group has never conducted an attack on American soil. After the targeted drone strikes against the Islamic State (ISIS) in 2016, its capacity was also greatly diminished. However, recent activity may suggest a resurgence of the group.

In a recent article, Hal Brands and Michael O’Hanlon summarise the efficacy of the US counterterrorism response after 9/11. “In Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Syria, and elsewhere, the United States has repeatedly disrupted or destroyed territorial safe havens carved out by the Islamic State (also known as ISIS), al Qaeda, and their offshoots and affiliates. It has also developed an unparalleled ability to decapitate terrorist organizations; decimate their ranks of financiers, facilitators, and operational-level commanders; and keep them under pressure and off balance.”

However, while the US may have met its original objectives, the nation building exercises in Afghanistan and Iraq were largely unsuccessful. America invested significant resources and manpower into protracted conflicts in both nations but failed to implement any durable changes. In fact, the American interventions created distrust internationally and disdain at home, fuelling partisan divides, emboldening jihadi recruitment and tarnishing the soft power of the US Government. Ultimately, the US prevented another large-scale attack domestically, eliminated the perpetrator of the attacks in Bin Laden and rapidly quelled the emergence of any new terrorist groups. By those metrics, the War on Terror achieved what it aimed to do but it did so at a significant cost to the US public.

Loss of Liberties

According to Toomey, “9/11 and Congress’ rushed passage of the Patriot Act ushered in a new era of mass surveillance and over the next decade, the surveillance state expanded dramatically, often in secret”. The Patriot Act and later the FISA Amendments Act, gave the NSA nearly unchecked authority to collect data on American phone calls, text messages and emails under the premise of targeting foreign nationals suspected of terrorism.

In addition to being unconstitutional, this surveillance was also ineffective. According to a newly declassified study, the NSA programme that analysed logs of Americans’ private correspondences, cost $100 million between 2015 and 2019 but yielded only one significant investigation.

Furthermore, Toomey asserts that the “human toll of government surveillance is undeniable”. He states that particularly for minority communities, routine surveillance is “corrosive,” making people feel as though they are “constantly being watched and chilling the kind of speech and association that democracy is based on.” Toomey goes on to state that the US domestic security policies enacted after 9/11 were harmful because they often “fed into a national security apparatus that puts people watchlists, subjects them to unwarranted scrutiny by law enforcement and allows the government to upend lives on the basis of vague, secret claims”.

Especially because these programmes were conducted in secret, people targeted under them had little means of grievance redressal. A notable example of such a programme is the existence of a no-fly list. For years the government denied that any such list existed and could not account for a system that has never caught a terrorist but has inadvertently caught citizens, many of whom were Muslims.

For Muslim communities in America, the laws that allowed their rights to be compromised were often just the tip of the iceberg. After the 9/11 attacks, Islamophobia in the US and Europe skyrocketed. Matthew Duss, a Foreign Policy Advisor to Bernie Sanders, writes about how Muslims in America were increasingly demonised by both political parties after 9/11, noting that Republicans often warned about the threat of “creeping Sharia,” paving the way for Trump’s Muslim ban and that Democrats talked about Muslim Americans being “the first line of defence against terrorism” which essentially pressured them “into service on the basis of their religion.”

The mass surveillance state and anti-Muslim rhetoric created an ecosystem of fear in the US which made communities suspicious of one another and emboldened extremists on both sides of the isle to justify acts of violence and mass shooting within US borders. Towards that end, Duss warns that “when fellow citizens are cast as enemies of the state, even a violent American insurrection can become real.” This threat is further exacerbated by the partisan divide which was made wider by disagreements over the War on Terror and its subsequent toll on human rights domestically and abroad.

Opinion of the US

Following Snowden’s exposé of NSA surveillance tactics in 2013 and the human rights allegations surrounding Guantanamo Bay, the US government was forced to contend with several of its own shortcomings. The US was derided as hypocrites internationally, while at home the campaigns had lost much of their original credibility. This in turn, hampered Washington’s ability to respond militarily to global emergencies and allowed states like Russia and China to justify their own human rights violations.

In terms of the first point, there is no clearer example than the situation surrounding Syria in 2013. When Syrian president Bashar al-Assad crossed Obama’s stated redline by using chemical weapons, the latter found that both the international community and the American legislature was reluctant to respond.

When Obama went to Congress for support for a military strike against the Assad regime (support he didn’t need under the AUMF) he was faced with bipartisan war fatigue which was mirrored amongst the American voters as well. He subsequently called off the attack and allowed his redline to be crossed without any reprisal. Ackerman describes this fatigue against war as a “glaring strategic liability,” arguing that “a nation exhausted by war has a difficult time presenting a credible deterrent threat to its advisories.”

Furthermore, the very rhetoric of counterterrorism has been co-opted by unscrupulous state actors. Patrycja Sasnal, in a report for the Council on Foreign Relations, points to the state of emergency enacted in Egypt as one example of this. She writes that “Egypt learned from the US Patriot Act how to structure its own counterterrorism bill,” drafting a broad piece of legislation that allowed the state to hold around 10,000 people without fair trial. Sasnal also references China and Russia, noting that following the post 9/11 War on Terror, “counterterrorism has become a pretext for other, unrelated policies globally,” allowing Beijing and Moscow to use it to “justify actions against opposition, activists, minorities, or interventions in third countries.”

America’s human rights violations and excessive response during the War on Terror also motivated other states to follow its playbook. In 2014, when Uyghur terrorists attacked Xinjiang in western China, Chinese President Xi Jinping urged his party officials to follow the Americans’ example after 9/11. This in turn resulted in a crackdown that would culminate in millions of Uyghurs being thrown into concentration camps. Similarly, as part of its counterterrorism initiatives, the US worked with governments in Egypt, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia, often at their own request. According to Hegghammer, Washington’s support for these countries undermined its democratic credentials which was then exploited by leaders like Putin in Russia.

While one may argue that the actions of these countries have no bearing on US citizens, such a notion would be short-sighted. The brutalisation of the Egyptian government catalysed the Arab Spring which led to increased instability in Syria and prompted the rise of ISIS. Likewise, the War on Terror diverted America’s focus away from China and Russia and was used by them to justify tactics that consolidated their own spheres of influence. Both are now significant security threats to the US and have been involved in actions and campaigns aimed at undermining US democracy.

Opportunity Costs

Much has been said of the actual costs of the War on Terror, which will continue to rise as the US fulfils its obligations to veterans, lenders, and allies. There have also been significant discussions surrounding the human cost of the war in terms of lives lost, refugees generated, and livelihoods disrupted. However, what isn’t often mentioned, is the opportunity cost of the War. The US last ran a federal surplus in 2001, relying on deficit spending to finance the War over the next two decades. According to Ackerman, during this time, hardly any politicians mentioned the prospect of a war tax but meanwhile “other forms of spending – from financial bailouts to health care and, most recently, a pandemic recovery stimulus package—generate breathless debate.” Ackerman asks readers to imagine what else the US could have done with those resources and political bandwidth as the “country struggled to keep pace with climate change, epidemics, widening inequality and diminished US influence.”

Additionally, partisan divides and the politically charged rhetoric of fear has given birth to a number of right-wing extremist groups across the United States, who feel justified in attacking minorities in alleged defence of America and American values. A 2020 DHS Threat Assessment Report even identifies Domestic Violent Extremists as the biggest terror threat to the US, noting that“racially and ethnically motivated violent extremists—specifically white supremacist extremists – will remain the most persistent and lethal threat in the Homeland.” Despite the massive shift in the nature of the threat, countering domestic terrorism only accounted for 8% of the DHS budget in 2017, with most of the rest going towards fighting international terrorist threats.

There is perhaps limited value in arguing in hypotheticals, but it is not inconceivable to think that millions of Americans would have been better served and protected if the money used to finance the War was instead diverted to areas such as healthcare and education. Likewise, if public officials and law enforcement spent less time focusing on the threat of Islamic terrorism, they would likely be better equipped to respond to other challenges. The costs of the War have been tremendous, possibly none more so than the political environment created in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. By focusing on international terrorism, the US allowed unsavoury international actors and domestic threats to flourish.

Ultimately, as Congresswoman Lee warned, America, in fighting terrorism, may have unwillingly become the very evil it deplores.

Source: Read Full Article