In a 1995 research paper, psychologists studying 'counterfactual thinking' analysed video footage of the 1992 Barcelona Games to deduce that the knowledge of ‘almost winning a Gold medal’ ruined the moment for a silver medallist, while the bronze winner was contended by the thought: ‘I at least won a medal’.

During a newspaper interview he gave almost 70 years after he clinched a silver medal at the Stockholm Olympics of 1912, mid-distance American runner Abel Kiviat described the race as a “nightmare”.

His silver medal had come after a photo-finish — a first in Olympic history — in which he had just got past fellow American Norman Taber in the 1500m race.

“That race was the biggest disappointment of my life. I never saw Jackson,” he said while referring to Great Britain’s Arnold Jackson who had secured by the slimmest margin of 0.1 seconds. “I wake up sometimes and say, ‘What the heck happened to me?” Kiviat said.

Kiviat, who died in 1991, showed that the disappointment of losing out narrowly lingers, but he was no exception in this regard. Most silver medallists end up tormenting themselves by imagining the alternative possibility if they had pushed a little harder.

Ravi Kumar Dahiya, the Indian wrestler who secured a silver medal for India in 57 kg freestyle on Thursday in the ongoing Tokyo Olympics, voiced a similar disappointment.

“What’s the point of this?… I had come here with only one target, a gold medal. This (silver medal) is okay, but it’s not gold,” he had told reporters.

A 1995 research paper published by psychologists Victoria Medvec, Thomas Gilovich (both from Cornell), and Scott F Madey (University of Toledo) has an answer to why silver medallists may be feeling the way they are.

They studied this phenomenon to conclude that on a happiness scale, silver medallists fair poorly owing to the human tendency to indulge in ‘counterfactual thinking’ — the propensity to think of alternative circumstances to real-life events, especially those with far-ranging consequences.

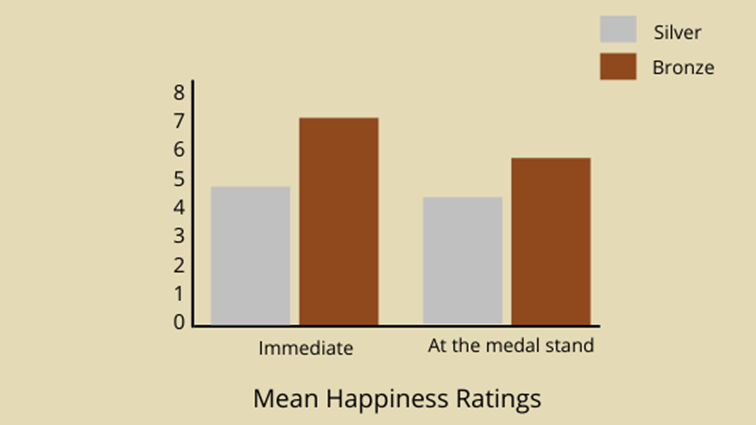

The study, “When Less Is More: Counterfactual Thinking and Satisfaction Among Olympic Medallists”, deduced that bronze medallists score much better on the happiness scale when compared to silver medallists who had outperformed them in the game.

Medvec and colleagues analysed visible expressions of the bronze and silver medal-winning athletes at the 1992 Summer Olympics immediately after the finish of the event when the winners stood at the medal stand.

The study aimed to determine how counterfactual thinking and the psychology of “coming close” affects the feeling of satisfaction and the degree of well-being. Medvec et al chose the domain of athletic competition outcomes to study the subject because it throws up results with an unusual precision with competitors finishing first, second, or third with a fractional difference and earning distinctly different rewards of gold, silver, and bronze medals.

“We were interested in whether the effects of different counterfactual comparisons are sufficiently strong to cause people who are objectively worse off to sometimes feel better than those in a superior state. Moreover, we were interested not just in documenting isolated episodes in which this might happen, but in identifying a specific situation in which it occurs with regularity and predictability. The domain we chose to investigate was athletic competition,” said Medvec and his colleagues in the paper published in The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

As part of the study, the researchers collated the video footage from the Barcelona Olympic Games held three years ago and edited them in three different master tapes. One showed the medallists’ reaction immediately after the results were announced, another showed them receiving the medals at the stand, and a third one comprised of the interviews they gave to media persons about their performance.

In the first study, the university students, who were blind to the results, were asked to judge the immediate reaction of 41 athletes on a 10-point ‘agony to ecstasy’ scale. After assessing athletes’ reactions, silver medallists received a mean rating of 4.8 while bronze medallists received a mean rating of 7.1 on the happiness scale. When examining the athletes’ reaction on the medal stand, participants assigned the bronze medallists a mean rating of 5.7 and a 4.3 for silver medallists.

In the second part of the same study, the participants reviewed television interviews of 22 silver and bronze medallists to see what was the predominant feeling expressed by each athlete: Was he/she happy with what was achieved, or was he/she preoccupied with a feeling of regret. The participants judged the expressed feelings on a 10-point scale which had “At least I…” on one end and “I almost…” on the other.

It was found that the silver medallists focused more on “I almost” than bronze medallists who expressed a feeling of achievement and satisfaction for getting a medal. Participants assigned silver medallists’ thoughts an average rating of 5.7 and bronze medallists’ an average rating of only 4.4 on the 10-point “At least I… ” to “I almost…” scale.

Explaining the findings, the researchers wrote, “To the silver medallist, the most vivid counterfactual thoughts are often focused on nearly winning the gold. Second place is only one step away from the cherished gold medal and all of its attendant social and financial rewards. Thus, whatever joy the silver medallist may feel is often tempered by tortuous thoughts of what might have been had she only lengthened her stride, adjusted her breathing, pointed her toes, and so on. For the bronze medallist, in contrast, the most compelling counterfactual alternative is often coming in fourth place and being in the showers instead of on the medal stand.”

Social psychologists have long held that an individual’s wellbeing in any given circumstance depends on how these circumstances compare with those with whom he tends to compare them.

Such counterfactual thinking also has a functional value as those who ruin their happiness by thinking about the missed opportunity often strive to improve their future performances.

“Downward comparisons (i.e., thinking about a worse outcome) are thought to provide comfort, whereas upward comparisons (i.e., thinking about a better outcome) are thought to improve future performance. Indeed, it has been shown that people who expect to perform again in the future are more likely to generate upward counterfactuals than those who expect to move on,” said the study.

Three other researchers who repeated the experiment in the 2016 Summer Olympic Game, confirmed that counterfactual thoughts were higher among the silver medallists than the bronze winners. They, however, found that the differences in the expressed emotion were trivial or negligible.

Source: Read Full Article