A Ramachandran’s exhibition titled ‘Gandhi: Loneliness of the Great’ opened at Delhi’s Vadehra Art Gallery on October 1

Mahatma Gandhi might have often been surrounded by people, but he also had moments of solitude and, at times felt alone, says artist A Ramachandran. It is this aspect of his life that the Delhi-based artist has attempted to depict in an exhibition titled ‘Gandhi: Loneliness of the Great’ that opened at the capital’s Vadehra Art Gallery on October 1.

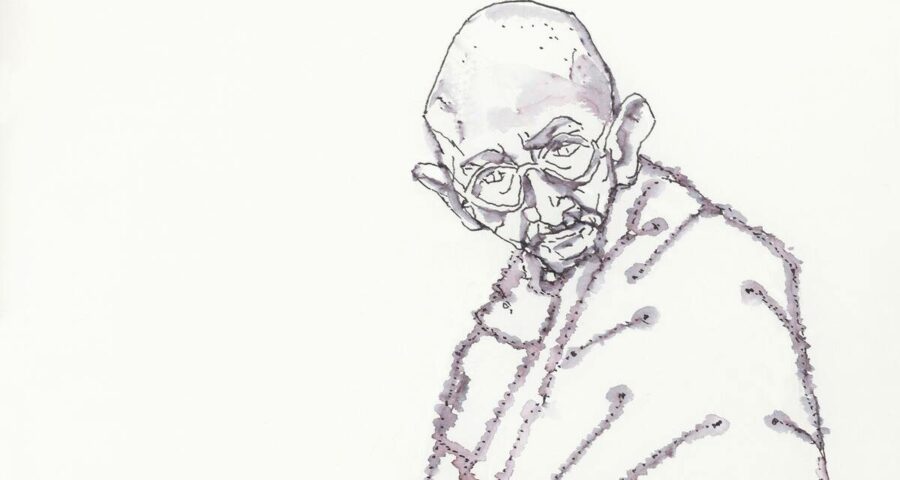

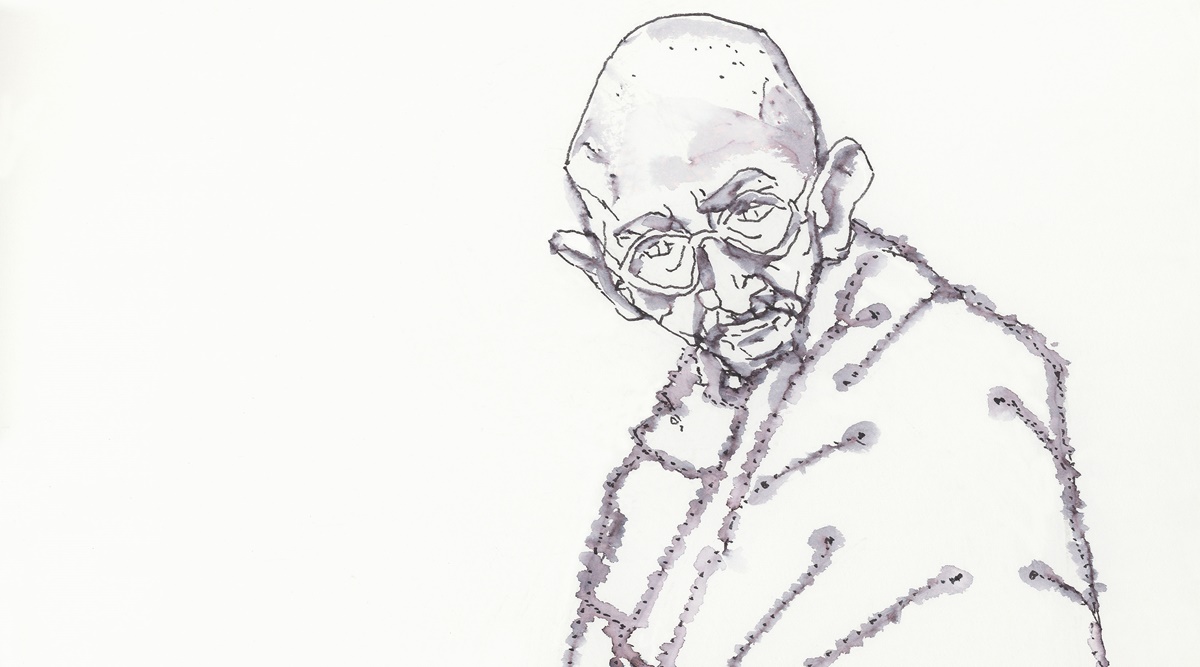

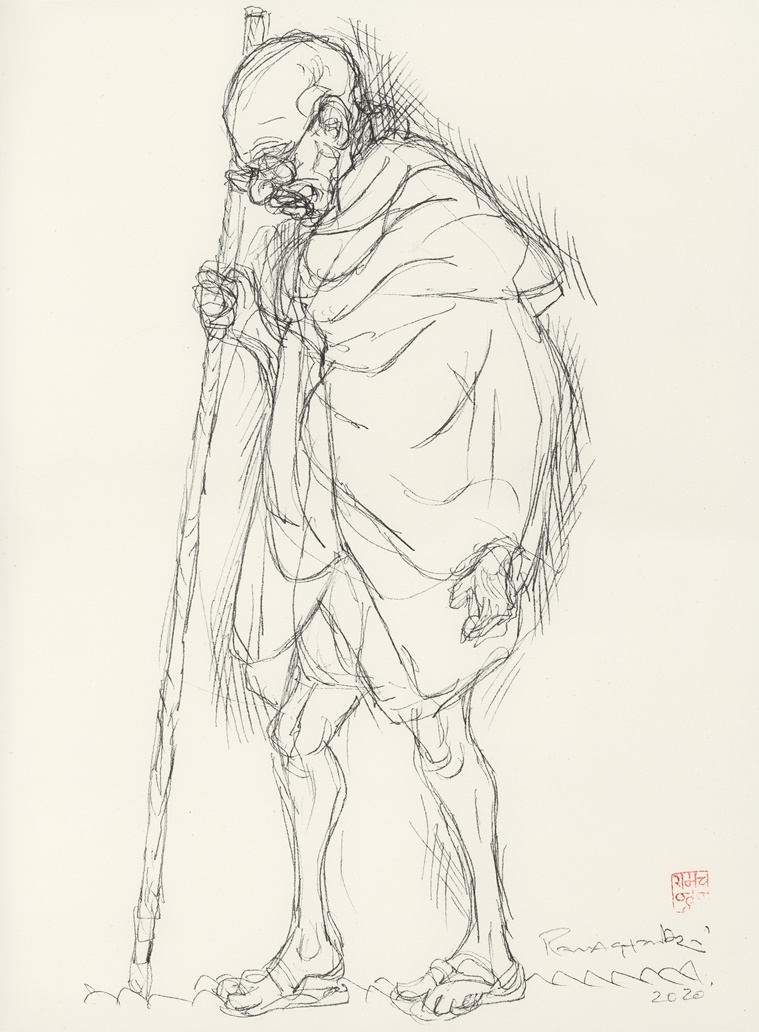

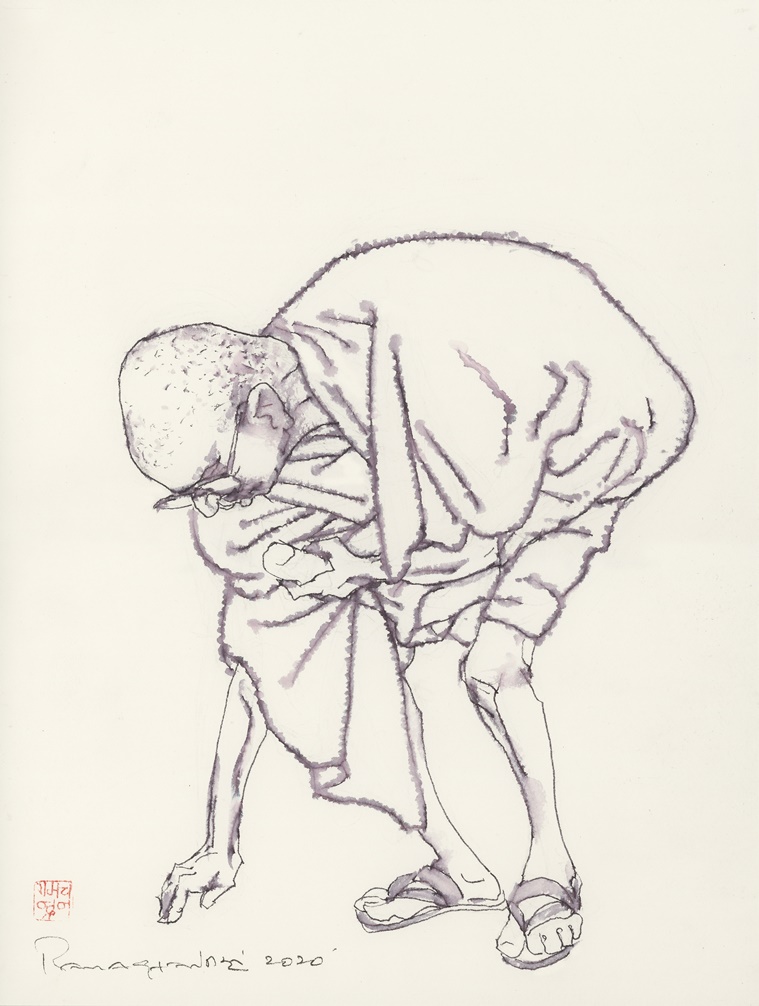

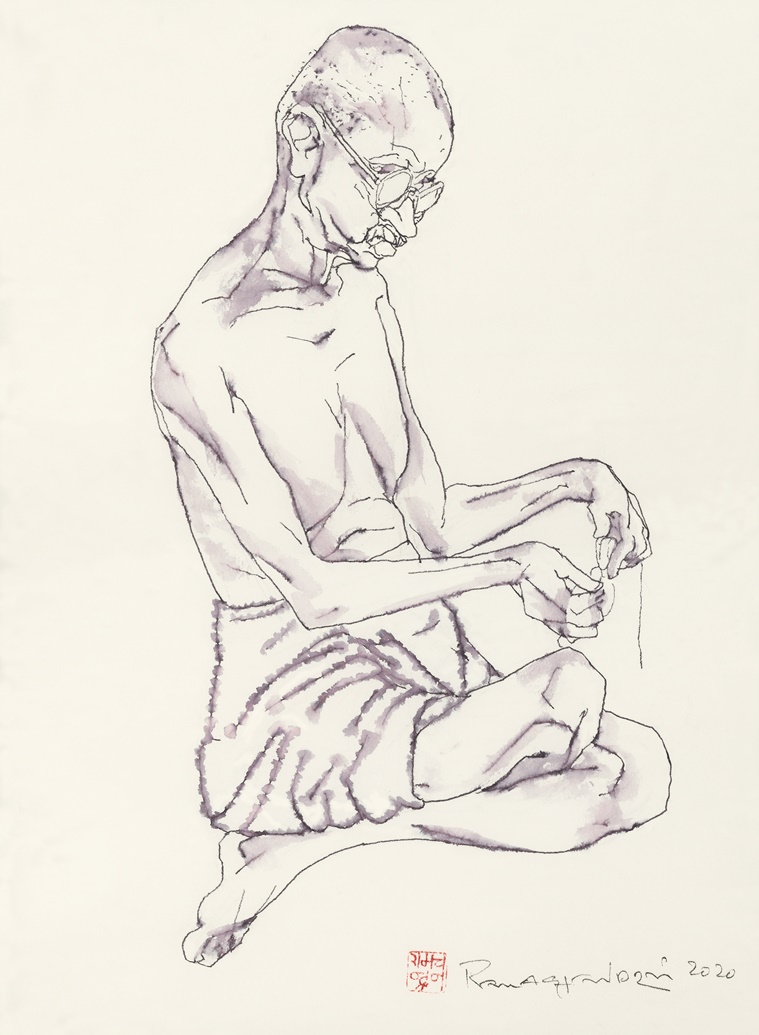

Featuring 20 pen, brush and ink drawings, the works celebrate not just Gandhi’s leadership qualities, but as art historian and critic Ella Datta notes in the accompanying catalogue, “his very human qualities — his loneliness, his humility, his infinite compassion, his grit and courage, his sorrowing sense of loss for what he encounters around him”.

Ramachandran, 86, who made the sketches during his two-month sojourn in Mumbai between December 2019 and January 2020, says: “From childhood, I was a great admirer and follower of Gandhiji.” The Padma Bhushan awardee recalls how, when he looked at photographs of Gandhi, he would feel the leader often seemed out of place with the crowd with whom he was seated. “If you carefully look, they give an impression of Gandhiji that I never thought of before. One of the most moving images is of him sitting with the body of Kasturba Gandhi. Seated in a corner of a room, he was staring at nothingness. It is one of the most touching photographs of a great man… He identified himself with the common man of India even in the physical gestures, way of sitting, leaning back, folding his hands, all these are great messages,” says Ramachandran.

Growing up in Attingal, Kerala, the artist’s first lessons on Gandhi and his ideals were imparted by his school teacher. Later, as a student in Santiniketan, he came across Nandalal Bose’s 1930 iconic linocut portrait of the Mahatma as well as the sculpture ‘Dandi March’ by his mentor Ramkinkar Baij. “The nucleus of the concept of modern Indian art was given by Gandhiji to Nandalal when he asked him to do the Haripura Congress Mandap. He asked him to use local materials and visual language to communicate with the people. That is a great message. We have not understood the significance of that,” says the artist, adding, “I also heard of this instance when, during one of Gandhi’s visits to Santiniketan, the sanitation workers did not come, so he cleaned the toilets himself. That was a big lesson for the entire ashram.”

The violence during the Partition also turned Ramachandran to find answers in Gandhi’s ideals. “It completely destroyed the edifice he built… Gandhiji is a tragic hero who fought for his ideals. He cannot be compared with any person in our political history,” says the artist-pedagogue, who taught in Jamia Millia Islamia University for almost three decades.

Gandhi has remained a constant in the artist’s thoughts and works. Ramachandran has depicted varied aspects of his persona — from his sketches in an exhibition in Kochi in 2019, to his 1969 mural Gandhi and the 20th Century Cult of Violence. In his 2016 seven-feet plus bronze sculpture titled Monumental Gandhi, he has a bullet hole on the back and the words “Hey Ram” engraved on the figure, the last words uttered by Gandhi when he was assassinated.

“I think his ideals failed in modern India because nobody followed him later. Whatever he worked for was cancelled out by the new ideas of a new world conceived by the later rulers of India. His idea of Panchayat raj or the upliftment of all stratas of society to a certain level was never practised. There is a great discrepancy between his leadership and the later notion of an independent India. He believed in humanistic principles which did not work in times of hard political bargaining. His philosophy was too idealistic, and in mundane life, people don’t have time for such greatness… We still claim to be followers of Gandhiji and respect him, but there isn’t much left, except in monuments and names of roads… These are only symbols used by politicians of what Gandhiji taught, for their own selfish ends. There aren’t any Gandhian ideals anywhere to be seen,” says Ramachandran.

Source: Read Full Article