Beijing's seemingly eco-conscious pledge could mend some bridges between China and the EU, say analysts, after relations between the two sides have worsened since early 2020.

Written by David Hutt

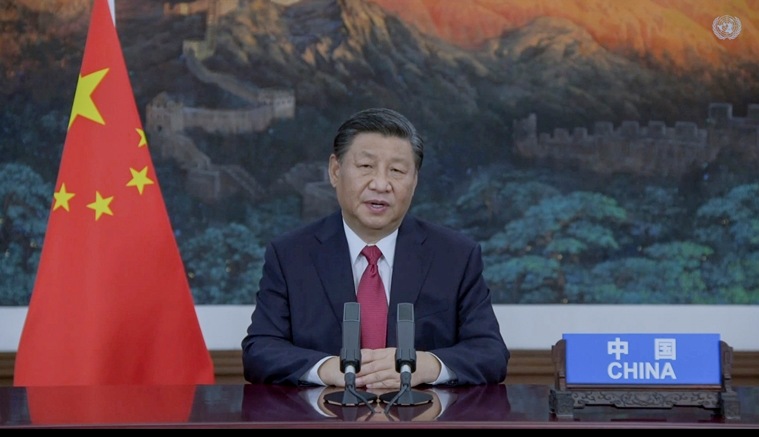

Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks remotely during the 76th Session of the General Assembly at UN Headquarters in New York on September 21. The announcement to stop building coal-fired power plants abroad was made by Xi Jinping in an address to the UN last week

The Chinese government made the surprise announcement last week that it will stop building coal-fired power stations abroad, a decision that could put it in the good books of the increasingly eco-conscious European Union.

The pledge was made by Chinese President Xi Jinping in a pre-recorded address to the UN General Assembly, although he gave few details and questions remain whether he meant China will cease financing coal plants overseas or merely stop building them, a far less impressive pledge.

South Korea and Japan said earlier this year that they would stop funding coal-fired power plants abroad, and with China the three Asian countries account for 95% of all foreign financing for coal-fired power plants worldwide, according to a report by Georgetown University.

In the past, Beijing had pledged to cease coal production by 2030 but last year it brought on line 38.4 gigawatts of new coal-fired power domestically, three times as much as the rest of the world.

EU-China tensions

Beijing’s seemingly eco-conscious pledge could mend some bridges between China and the EU, say analysts. Relations have worsened since early 2020 over China’s human rights record, its actions during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and its increasingly assertive foreign policy objectives.

Tensions came to a head in March this year when the EU imposed economic sanctions on four Chinese officials in Xinjiang province, where communist authorities are accused of mass human rights abuses against the Uyghur Muslim population.

Hours later, Beijing responded by sanctioning several European politicians and regional think tanks.

In the aftermath, the European Commission halted ratification of an investment pact the EU had controversially agreed with China last December.

“Since the collapse of the EU-China investment agreement earlier this year, European officials have been searching desperately for ways to re-engage with Beijing,” said Noah Barkin, a Europe-China expert at US research group Rhodium.

“Xi’s coal pledge will reinforce the view that climate is an area where cooperation is still possible,” he added.

However, it remains unclear whether China has pledged to stop funding the construction of coal-fired power stations abroad or merely to stop building them overseas.

Zhao Lijian, a spokesman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, dodged the question at a press conference last week, directing reporters to the statement made by President Xi that Beijing “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad.”

But comments made by senior EU officials would suggest they reckon Xi meant funding. “Excellent news… that China joins EU and others to end financing of coal abroad,” European Commission Vice President Frans Timmermans tweeted on September 22.

Still, it’s not clear what Beijing’s announcement means for EU-China relations.

“The devil is in the details,” said Bonnie Glaser, Asia Program director at the German Marshall Fund. If China did stop its financing of coal-fired power plants via its Belt and Road Initiative, a multibillion-dollar global investment plan, it “will be welcomed” by the EU, Glaser said.

“But it won’t remove European concerns about many other issues such as China’s human rights and predatory trade policies,” she added.

The move might improve Beijing’s image among the European public, though. China’s impact on the global environment is one of the issues most negatively perceived by ordinary Europeans, whose opinion of China has also worsened since early 2020, according to a survey of public opinion by Sinophone Borderlands, a project at Palacky University Olomouc in the Czech Republic.

Richard Q. Turcsanyi, who is the lead researcher of the survey published this year, described China’s pledge as a tactical and clever move.

“There are many other aspects of China’s interactions with the EU that are perceived negatively, such as human rights and governance. Obviously, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) doesn’t want to address those things,” he said.

However, China’s impact on the global environment is a “low-hanging fruit” that doesn’t impact the political standing of the CCP at home but has the potential to improve its reputation abroad, he added.

Rising environmental demands

The EU is increasingly upping its environmental demands not only for its own regional agenda but also for its cooperation with the rest of the world.

Funds to member states now have more conditions on green policies, while the EU is also considering revising its global trade privilege scheme for developing countries in 2024 to attach conditions on climate action.

“The timing, in the midst of new strains in the trans-Atlantic relationship over the Australian submarine deal, was impeccable from Beijing’s point of view,” Barkin said, referring to the new alliance between the US, UK and Australia announced this month that has sown divisions between European countries and the US.

“The climate is likely to become a growing source of friction between China, Europe and the United States as the competition over green technologies heats up,” he underlined.

Source: Read Full Article