New concrete, metal and razor wire walls, together with drone surveillance, beefed up border patrols and catch-and-return policies have made the route to Europe more difficult, dangerous and costly.

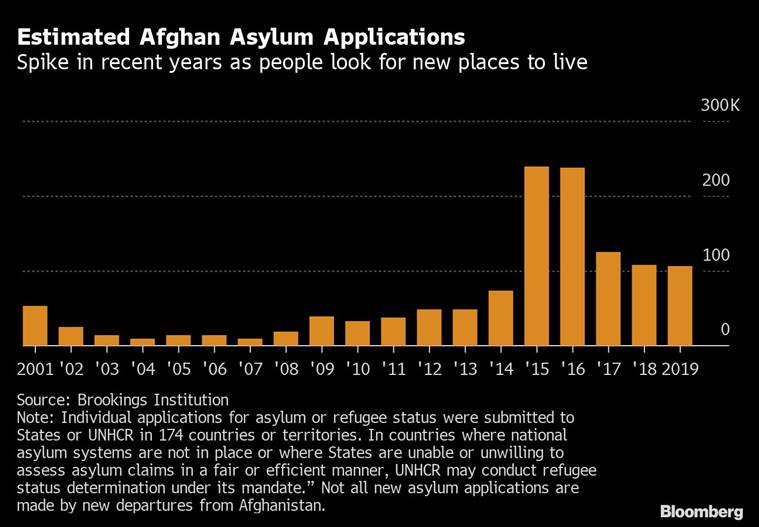

In 2015, Turkey became a kind of human superhighway for refugees fleeing to Europe from Syria and elsewhere, a migration of at least 1.3 million people that had a seismic impact on the politics of the European Union. Many of the bloc’s leaders now fear a repeat, yet it is far more difficult for desperate Afghans to reach Europe than six years ago.

New concrete, metal and razor wire walls, together with drone surveillance, beefed up border patrols and catch-and-return policies have made the route to Europe more difficult, dangerous and costly.

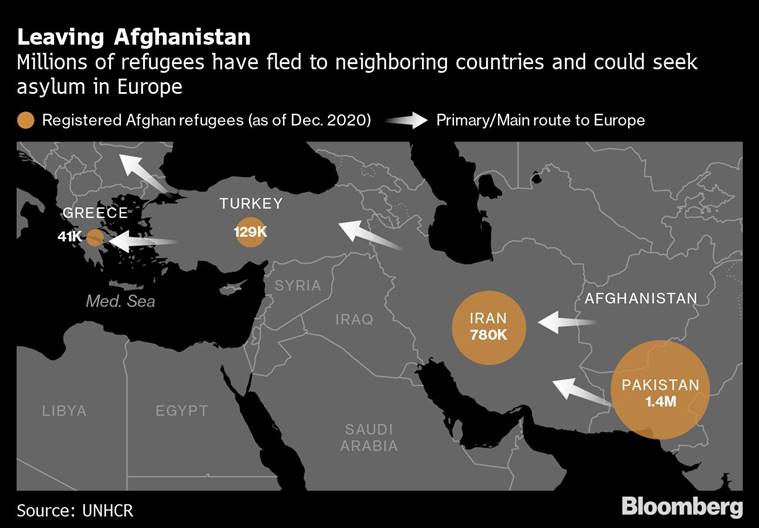

An EU plan to fund Afghanistan’s neighbors to host those who leave – the UNHCR has estimated the number could reach 500,000 by the year’s end – could also make it more inviting to stay put.

“Europe is right to be concerned, but I don’t think it is likely and don’t think it is imminent,’’ Michael O’Hanlon, director of foreign policy research at the Brookings Institution, said of the risk of another 2015 crisis.

For a start, at about 4,800 km (3,000 miles) it’s three times as far from Kabul to the nearest European border as from Aleppo, in Syria. Even six years ago, when Afghans made up the second-largest contingent of new arrivals in Europe — 193,000, compared to 378,000 Syrians, according to data collected from EU states by Pew Research — many were already outside Afghanistan and saw an opportunity to improve their lot.

For now, despite an airlift of more than 100,000 Afghans and their families who had worked with allied forces, the number of Afghans attempting to exit by land since the fall of the former government has been modest, according to the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR.

That shouldn’t come as a surprise, says O’Hanlon, because the period of turmoil when the Taliban were recapturing territory from the former government has now mostly ended.

All of this could easily change if the security situation worsens significantly, the Taliban return to the worst of their brutal Islamist rule in the 1990s, or a combination of economic collapse, Covid-19 and drought should lead to starvation. The UN’s World Food Program warned this month that 14 million Afghans face food insecurity this winter.

Iran

If the worst does happen, the road to Europe is much changed since 2015. On the main route from Afghanistan, Iran has been the first stop since Afghans escaped the country after its invasion by the Soviet Union, in 1979. Another surge followed the Soviet retreat ten years later, as the nation descended into civil war, another after the Taliban took power in 1996, and yet another earlier this year. Most refugees stayed in Iran, and Pakistan.

By now Iran is home to 780,000 registered and at least 2 million more unregistered Afghan refugees, according to the government in Tehran. As many as 500,000 new emigrants crossed in the last four months, as the Taliban retook the country, Fatemeh Ashrafi, a director on the board of the Tehran-based Hami Association, which provides support to refugees, told Iran’s Etemad newspaper last week. Another 7,000 crossed since the Taliban captured Kabul in mid-August, Ashrafi said.

On Aug. 18, Iran said it would bar further Afghans, reversing a pledge to temporarily house people fleeing the Taliban. With many ethnic and family ties across a porous 900 km border that ban will be hard to enforce. And because the country’s resources are spread thin because of sanctions and the region’s worst coronavirus outbreak, authorities are likely to take a tougher stance against the latest influx of refugees. More troops have been deployed to major border crossings on the frontier.

In November, the parliament in Tehran tightened laws on illegal arrivals by imposing tough prison sentences and allowing police to shoot at vehicles suspected of trafficking people. At the same time, Iran said in April it would end cooperation with the EU on people smuggling.

Turkey

The next country for Afghan refugees to cross is Turkey, where President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s approach has undergone a sea change under pressure from a domestic backlash against the approximately 5 million mainly Syrian refugees that Turkey already hosts. From highlighting an open door policy to protect fellow Muslims, and occasionally threatening to bus them to the EU’s borders in times of diplomatic strain, Erdogan is now building walls to halt the flow from the east.

Turkey has lined 156 km, or just under 100 miles of its 560 km Iran border with a three meter high concrete wall, topped by razor wire. Another $30 million, 64 km section is underway, funded partly by the EU. The tactic helped staunch the arrival of refugees from Syria, with 837 km of that 911 km border walled off. Plans are also in place to wall the 33 km frontier with Iraq.

“We are very sensitive about immigration,’’ Erdogan said in Istanbul, on Aug. 27. “We are building walls almost everywhere.”

Turkey has also deployed 3,500 extra border troops in an effort to capture illegal migrants, beefing up the border walls with flash floods, thermal cameras and motion-sensors, as well as razor wire and minefields. Drones surveil the frontier 17 hours per day, according to Turkey’s interior ministry.

For sure, no wall can keep the desperate out entirely. Smugglers throw blankets onto the razor wire so migrants can climb over and dig covered pits to hide them from drones, according Atanur Aydin, police chief for the border province of Van.

Greece

Greece last month completed a taller, electronically monitored metal fence covering 40 km of the most sensitive points of its border with Turkey. Citizen Protection Minister Michalis Chrisochoides, since removed in a cabinet reshuffle, said at an Aug. 20 unveiling ceremony that Greece would allow no “erratic movement’’ over its borders.

At the same time, the narrow straits between the Turkish mainland and the easternmost Greek islands that so many Syrian, Afghan and other refugees risked their lives to cross in 2015 are now subject to patrols by Turkey, Greece and the EU’s Frontex border mission.

Top News Right Now

Click here for more

According to the UNHCR, 5,309 refugees arrived in Greece from Turkey in the year to Aug. 29, with just 1,890 of those coming by sea. In 2015 there were 861,630 arrivals, with just 4,907 of those coming by land.

North Africa

Refugees have a history of finding new routes once old ones are blocked and today is no different. More migrants are trying to make the crossing to Europe from North Africa than Turkey.

In the first half of 2021, Algeria, Libya, Tunisia intercepted almost 25,000 refugees as they tried to reach Europe by boat, about half the number of successful landings recorded, while Turkey intercepted just under 7,000, according to the UNHCR. Amid that effort, 1,146 people lost their lives.

Yet as important as any barrier is the determination of Europe’s governments to do whatever it takes to avoid the boost the 2015 refugee crisis gave to far right political parties across the continent. No matter what happens in Afghanistan, said the German-American political scientist Yascha Mount, speaking at the Lennart Meri security conference in Estonia Friday, “it will not lead to a repeat of 2015, because the political will is there to make sure it doesn’t.”

Source: Read Full Article