“This is just a very small step forward. The pace is extremely slow. We are moving in inches when we need to gallop in miles,” said Harjeet Singh, senior advisor with Climate Action Network International, a large group of NGOs working in climate space.

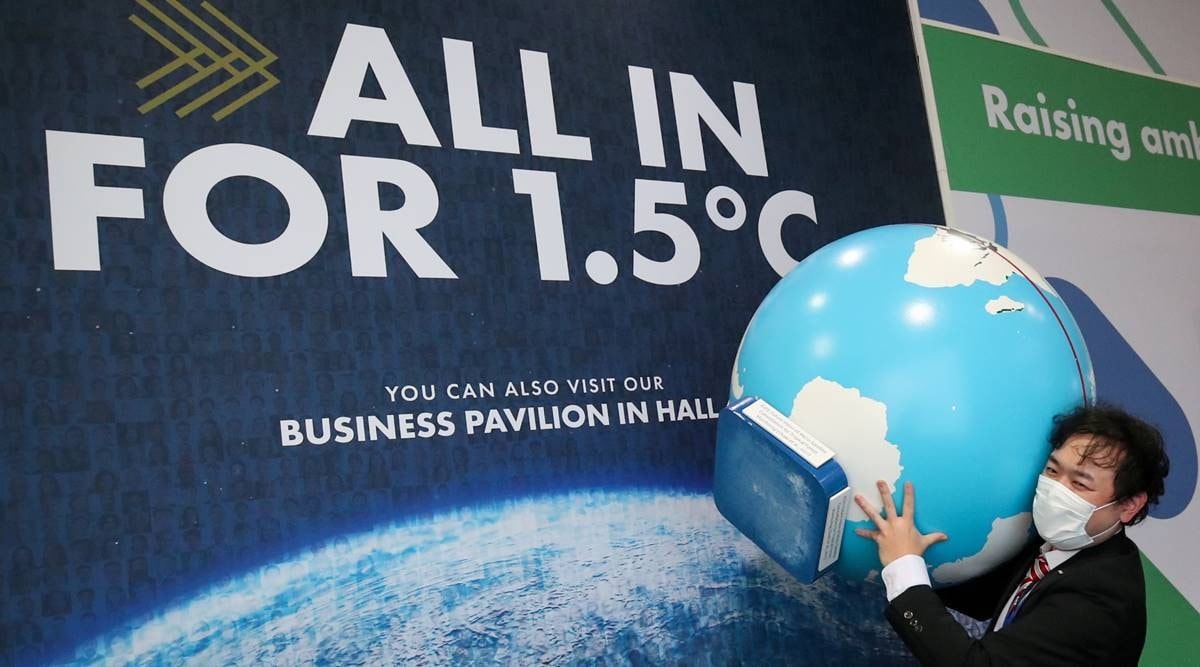

After India and China were able to force through an amendment on the language calling for phase-out of coal and fossil fuel subsidies in a dramatic last-minute intervention, countries at the Glasgow climate change meeting adopted a Glasgow Climate Pact aimed at keeping hopes alive for meeting the 1.5 degree Celsius temperature goal.

The pact fell far short of the expectations of a bold and ambitious agreement but countries still hailed it as an important step forward in the efforts to keep global temperatures from rising beyond 1.5 degree Celsius from preindustrial times.

“It is a very small step forward. The pace is extremely slow. We are moving in inches when we need to gallop in miles,” said Harjeet Singh, senior advisor with Climate Action Network International, a large group of NGOs working in climate space.

Hours after the final agreement was adopted, sharp differences had come to the fore over the reference to phase-out of coal and fossil fuel subsidies. India, China and several other developing countries, including Iran, Venezuela and Cuba, objected to this provision that called upon countries to accelerate “efforts towards the phase-out of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”. This was the first time that a phase-out of coal had explicitly been mentioned in any decision of the climate change meetings, and was seen as one of the progressive elements of the agreement, particularly by the civil society groups.

India’s Environment Minister Bhupendra Yadav argued that developing countries must not be denied the opportunity for development.

“The UNFCCC (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) refers to mitigation of GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions from all sources. UNFCCC is not directed at any particular source…. Targetting any particular sector is uncalled for. Every country will arrive at net zero emissions as per its own national circumstances, its own strengths and weaknesses. Developing countries have a right to their fair share of the global carbon budget and are entitled to the responsible use of fossil fuels within this scope,” Yadav said at one of the final meetings in Glasgow on Saturday.

“In such a situation, how can anyone expect that developing countries can make promises about phasing out fossil fuel subsidies? Developing countries have still to deal with their development agendas and poverty eradication. Towards this end, subsidies provide much needed social security and support,” he said.

Yadav put forward an example where subsidies on fossil fuels was useful from the development and health perspectives.

“We are giving subsidies for use of LPG to low-income households. This subsidy has been a great help in eliminating biomass burning for cooking, and has improved health of women and in reducing indoor air pollution,” he said.

Backed by China and many other developing countries, India later moved a proposal to amend this provision to substitute the word “phase-out” with “phase-down” in the context of coal, and to include a recognition of the different national circumstances of some countries. The final provision called upon countries to escalate efforts “to phase down unabated coal power and phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies while providing targeted support to the poorest and the most vulnerable in line with national circumstances…”.

Many countries expressed their disappointment at this “dilution” but gave their agreement nonetheless, paving the way for the adoption of the Glasgow Pact after two weeks of intense negotiations.

While the tussle over coal grabbed most attention in the final hours of the meeting, the 26th Conference of Parties of the UNFCCC, or COP26 for short, would also be remembered for the failure of the developed countries to meet their 12-year-old promise of mobilising at least US$ 100 billion in climate finance to help the developing world deal with the impacts of climate change. This money was supposed to be raised every year from 2020 onwards, but the deadline was pushed to 2023 just ahead of the Glasgow conference.

The Glasgow Climate pact noted this failure “with deep regret”, and asked the developed countries to deliver on this promise urgently. It also initiated discussions on quantifying a new target for climate finance, upwards of US$ 100 billion, to be mobilised every year from 2025.

Glasgow delivered some important successes as well. In response to the demands from the developing countries, and in keeping with the commitment of Paris Agreement, a new process has been initiated to define a global goal on adaptation. The Paris Agreement has a global goal on mitigation, defined in terms of temperature targets. It seeks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in amounts sufficient to keep the

rise in global temperatures to within 2 degree Celsius from pre-industrial times, while pursuing efforts to limit this under 1.5 degree Celsius.

But a similar goal for adaptation has been missing, primarily because of difficulties in setting such a goal. Unlike mitigation efforts that bring global benefits, the benefits from adaptation are local or regional. There is no uniform global criteria against which adaptation targets can be set and measured.

Glasgow Climate Pact has set up a two year work programme to define an adaptation goal.

COP26 also resolved the long-pending issue of carbon markets which had been holding back the finalization of rules and procedures for the implementation of the Paris Agreement. Countries, regions or even companies are able to trade emissions reductions in a carbon market. An entity looking to achieve emission reduction targets but unable to do so can buy carbon credits from other entities who have been able to make more reductions than they are required to.

In a big concession to major economies like India, China or Brazil, the COP26 has allowed old carbon credits, earned under the Kyoto Protocol mechanisms, to be traded in the new carbon market being set up, provided these credits have been earned after 2012. Countries have been allowed to use these credits to achieve their emission reduction targets till 2025.

COP26 also came very close to setting up a facility on loss and damage, a reference to the huge damages suffered by countries due to climate disasters. Least developed countries, the small island states, and the Africa group have been very vocal in demanding a loss and damage mechanism that can help with relief and rehabilitation efforts after a climate change disasters. The Glasgow meeting had substantial discussions on loss and damage after eight year, but it stopped short of creating a facility that was being demanded. Instead, it only established a dialogue to discuss the funding of activities to deal with loss and damage.

Source: Read Full Article