We are still in the middle of a negotiating a crisis… the crisis is nowhere near over until Depsang, Gogra [are resolved], says former NSA and Ambassador to China

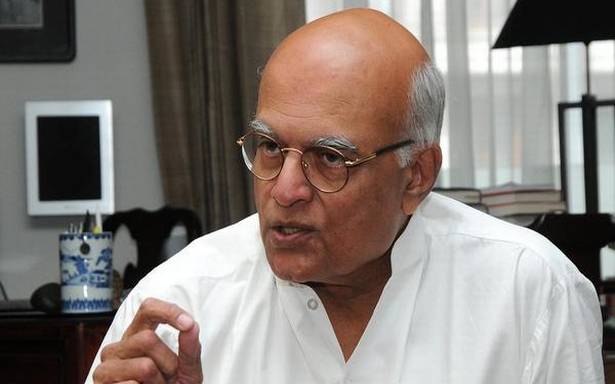

Shivshankar Menon, a former National Security Adviser, Foreign Secretary and Ambassador to China, traces the history and evolution of India’s foreign policy and place in the world in the new book, “India and Asian Geopolitics: The Past, Present.” He argues the country is served best when interconnected with the world and not by turning inward. The world, he says, is now facing a hinge moment, which will require India to be clear-eyed in its vision of what it seeks in the international order, and particularly in crafting a new modus vivendi with China after last year’s crisis. Excerpts from an interview.

The very first sentence of your book tells us the Indian subcontinent is the only subcontinent in the world. Do you see, as a result of this, an inherent tension between our sense of uniqueness, perhaps even exceptionalism, and our place in the broader region and world?

There is. In fact, that is precisely why I start the book with that, because it seems to me that because we’re the only subcontinent, we are part of a larger continent and we’re aware of that. But we also have a very strong sense of our own exceptionalism, of our uniqueness, of how different we are. Therefore there’s always a tendency to actually draw down the shutters, withdraw to our own home. That’s the main point of the book actually, because that worries me, the fact that I think we have something of that withdrawing going on right now.

For me, the lesson of our history and experience since Independence is that India does best the more connected she is with the rest of the world, the more engaged she is with the rest of the world. That is proven, right through history over and over again. It is those parts of India which were connected to the world through the Indian Ocean, the whole east coast of India, the Coromandel coast, all the way up to Bengal, and the west coast, Malabar, all the way up to the Gujarat coast, that were the most advanced economically, the most prosperous, the most stable core areas in terms of civilisation and culture, and the ones most in touch with the rest of the world for the last 3000 years or more.

For me, that’s the important lesson that I drove from our geography, because, as you said, with this strong sense of exceptionalism when things get tough outside, it’s easy to say, ‘forget the world’. Self-reliance can tend to become autarky, and that’s where I think there is danger. The book is actually a plea for engagement with the world, even though things have got very tough when you look at the global economy, geopolitics, etc.

Going back to the early years after 1947, your book reminds us how difficult the situation was at home even as our leaders were thinking through our place in the world, and yet we were actually punching above our weight in terms of global influence.

I think that is because we had a vision of ourselves, of our own role, of our place in the world, our place in world civilisation. That actually prevented us from choosing short-term maximalist solutions, as most politicians would. In fact, in some ways, it helped that we had a vision. It helped us to overcome the limitations of capacity and capability, of a very difficult bipolar Cold War world which was being formed at that time. And it enabled us because we had this sense of who we were and of our own interest, and got our priorities right.

Our priority was transforming India, the lives of the Indian people. That was our priority, everything else was to serve that. I think because we got that right, we managed to come out of a very difficult situation after Partition. And after the Chinese moved into Tibet, our whole geopolitics had changed, quite apart from the fact that, if you think of it, we were fighting a war from day one, we were dealing with refugees from Partition.

For me, it is quite amazing what they did in those first few years, against so many odds stacked up against them, that initial generation of leaders. Not that they agreed on everything or they all thought alike. Not at all, but they had an awareness of being engaged in something much bigger. And they weren’t playing day-to-day politics with these big issues, which is why many of the things they did at that time have lasted, and why we’ve gone back to that in various forms. You might say, well we are no longer now non-aligned . But when we say strategic autonomy, we mean exactly much the same, that we keep the power of decision-making in our own hands on big issues. So for me, that’s actually a very important formative period.

The other thing we tend to forget, because we now take all this progress for granted, is the very difficult legacy that imperialism actually left us because they built a sub-imperial system centred on India. In much of Southeast Asia and East Asia, Indians were the enforcers of imperialism and colonialism. The Shanghai policemen, for instance, who had to enforce signs on the parks saying ‘No dogs and Chinese’. You know, that’s not a memory that people forget very easily. And yet, thanks to what we did — and here the credit goes really to Nehru and to his sensitivity — within a few years, that legacy was actually wiped out because of his very active role in decolonisation.

If you look at it, those weren’t easy choices, and those were not unanimous choices in the leadership. There were some who thought we should continue to play the role that Britain had before of being a security provider all the way to Australia, etc. So, actually that was a pivotal period, when many of the basic lines of policy were laid down at that time.

That India decided to be outspoken, for instance, on decolonisation as it unfolded in Asia and Africa, or that Nehru championed this idea of pan-Asian solidarity, wasn’t so much rooted only in idealism but driven by a sense of realism as well?

If you look at what Nehru wrote internally, it’s quite clear that he had a fairly solid realist understanding of what was going on in the world, and he knew the limits of power. But he used other things – soft power, essentially, in various forms and alliances, building a broader coalition of countries. That is what happened, whether it was the Asian Relations Conference, or the Bandung Conference, or what ultimately became the non-aligned movement in the 1960s. In all this, what was he doing? He was compensating for India’s lack of hard power, but getting our way and doing it with others in a way that worked very well actually. He made some big mistakes. And I go through some of those in the book. But by and large, I think the basic lines of policy that he laid down for that time, I find it quite remarkable that he managed to do that.

We are at another hinge moment globally today. My belief is not that we have suddenly got a multipolar world ready to go. We are between orders today, and the world is really quite confused. It might be economically multipolar, but that’s it. The rest of it – military power, political power – we are still between orders. There are multiple ways in which we could go. But this is a time when it’s important that we be very clear-eyed in our vision of what we seek in the international order and how we work with the order, in order to transform India.

Ensuring “a rules-based order” is the phrase that’s flavour of the moment. Your book reminds us of the foundational myths of this liberal order, which, as you put it, was neither liberal nor rules-based for most of Asia. You also point out that non-alignment had a realist basis, and for a middle power that made the most sense. Are there lessons that we can draw from that period in how middle powers navigated the world then and how they need to navigate it now?

I do think that, yes, as you said, this idea of a liberal, international rules-based order was really a post-hoc creation, and I think it’s very successful propaganda actually because most people in the West have convinced themselves that this was a liberal order. For Asia, if you look at the Cold War, the killing fields were all in Asia. That’s where all the battlefield casualties took place, and the wars whether it was Korea, Vietnam, some of the wars that we were involved in, what happened in the Middle East, this whole series of Cold War conflicts. So when people talk of the Cold War as a long peace, it might have been peaceful in Europe! It might have been peaceful between the superpowers, but it was not peaceful for the rest of us. And it certainly wasn’t liberal because we didn’t have a say in the order.

The difference I think is that for India, there was a clarity of purpose. We knew what was important to us and what we wanted. We don’t like to say it but the fact is the Cold War binary, bipolar world made non-alignment possible. You could deal with both sides, you could get what you could from both sides, you could try and generate a competition between them in terms of assistance. How did you build the IITs? You go to one side which says yes, then the other one wants to compete and produces another IIT. This is benign competition, actually. And in a sense, it’s using bipolarity. So yes, the Cold War also created space for you to carry messages for instance, during the Korean War, or to work with both sides to try and enlarge what Nehru used to call the area of peace.

History never repeats itself exactly. It’s not as though we are suddenly now in a bipolar world where China and the U.S. have replaced the Soviet Union and the U.S. China and the U.S. are co-dependent economically. They are not like the Soviet Union and the U.S. were, nor is China offering an alternate order. China, in fact, is the greatest beneficiary of the U.S.-led economic order, if you look at what she achieved over 40 years of almost 10% growth. She is not saying we want a whole different order. The Soviet Union stood for a very different ordering of society, the economy, politics, everything. There was a socialist bloc, and there was the capitalist bloc from their point of view. That’s not what we’re seeing today. So it’s not as though we can therefore say, what we did then – we build a broad coalition of middle powers, we work with everybody else, we do the same, we play them both against each other – those are not the options today.

Secondly, your interests have also grown tremendously, compared to what they were earlier. Today, we are much more connected to the world than we were. Almost half our GDP depends on the external sector. Maritime security across the whole Indo-Pacific today really matters to you, when 38% of your trade goes through the South China Sea. So freedom of navigation in the South China Sea matters to you.

You have a much more fraught geopolitical situation. You are now next to the centre of gravity of world politics, whether you like it or not. It is the rise of China, it is a push back against that, it is China-U.S. tensions. During the Cold War, the problem was in the Fulda Gap, the centre of gravity, or at least the central fault line, was between the Soviets and the Americans in Europe. Not here. So you were, in a sense, a sideshow backwater, and that gave you some space to operate.

Today, both the Americans and the Chinese are busy working on the Nepalese – the Americans to get the Nepalese to sign on to a free and open Indo-Pacific, and the Chinese, because of Tibet and other interests, are actually involved in internal Nepalese politics and trying to keep the Communist party together. This is a very different situation from the old Cold War. So while there are lessons to be learned at the broadest level — about clarity of purpose, about looking at various options, and working within an existing balance of power but trying to improve it, etc — I don’t think you can draw direct lessons, for instance, that we were non-aligned then so we must be non-aligned today.

Today, we need to draw our own lessons from what we see around us. There are some that maybe sound like or look like the past. I do think that we can work with a much broader range of powers than just working with major powers, because there are other countries which share our interests. But I think today we couldn’t make the economic choices we made in the 1950s and 1960s. We are part of the world, we are dependent on the world, for energy, for raw materials, for technology, for a whole host of things. So we need to actually get out there and engage.

My fear is that we might be going in the wrong direction. We walked out of RCEP [the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership trade agreement] and we are the only major economy which is not part of any regional trading arrangement. We have raised tariffs steadily for the last four years. By doing all this, we are saying that we don’t think we’ll be competitive for the next 20 years, because 20 years was the adjustment period under RCEP. That’s not a good message to send either to your own people or to the rest of world. And in fact, by doing this, we are guaranteeing that we won’t be competitive, because we’re not even there. We’re not part of global supply or value chains. We need to actually make ourselves more competitive rather than less, and more engaged rather than less, at a time like this. That’s one reason why I wrote the book.

On China, the book looks deeply at the 1950s and at the moment that led to 1962, including at one revealing 1959 demarche from Chinese Ambassador Pan Tsuli that made a realist case for why both countries needed to find some form of accommodation. Was that argument missed or made impossible by the mood of the time?

I think a bit of both. I think that message, that look, China has other things to worry about — meaning the U.S. in the east — that they don’t want to face two fronts, and asking, ‘Would you like to face two fronts?’, in other words, threatening you with Pakistan. I’m not sure how much of that actually went home. Besides, there was an instinctive sort of revulsion against geopolitics or power politics, which is what this was. This was raw power politics and made you say, ‘we have other things to worry about, you don’t want two-front problems either, so let’s at least learn to get along.’

As I try and describe in the book, if you look at the overall situation in 1959, that’s when the Dalai Lama came across the border, that’s when Tibet was up in flames, you had floods of Tibetan refugees coming, and China had just revealed the full extent of her boundary claims in January. So all in all, public opinion was really inflamed. And there wasn’t much room for manoeuvre. And unfortunately, I think we approached it, like all countries do, from our own point of view.

When Zhou Enlai came in 1960 with an offer — which maybe was interim, we don’t know — I think Nehru tried to show him the depth of feeling and how difficult it was for him to compromise, by sending him to each of his ministers and some of the stalwarts, Vice-President Radhakrishnan, Govind Ballabh Pant the Home Minister, and so on. And those conversations were disasters, because we did it as we would among ourselves, openly saying, ‘Look, this is terrible what you’ve done, how could you do this?’

Zhou Enlai thought he was being set up, which is what it would have been in reverse if Nehru had had to go from one Chinese leader to another and listen to lectures about Indian bad behaviour, it would have been an organised performance in order to convey a message. Zhou Enlai being Chinese took it the Chinese way. We thought we were being open and frank. Nehru spent a lot of time, over 20 hours one-on-one with him with just interpreters in the room, going through it and trying to explain to him the limits, that what he was asking was not possible, and so on.

So it’s a combination of both things that you mentioned, that maybe we didn’t pick up some of those realist signals, but also I think of mutual misunderstanding on both sides. Then I think it got involved not just in our politics, but it got involved in Chinese internal politics. I think that is really what made the war inevitable, because it was part of Mao’s comeback strategy after the Great Leap Forward and the disasters of the famine.

Coming to the current situation with China, in the second half of the book you deal with the present and China is one of the relationships you explore. You outline how we came to this 1988 understanding that we continue negotiations on the boundary while preserving the status quo, we agree that differences don’t come in the way of cooperating elsewhere. Does this post-1988 model not hold anymore?

Some of us have been arguing for some time, for a little more than a decade in fact, that the old modus vivendi no longer works. Those signs of stress were clear. You saw it in the difference between what the Chinese did at the Nuclear Suppliers Group in 2008 and what they did when we went for NSG membership in 2015. You saw it in the escalating series of incidents on the border, whether it’s Depsang in 2013, Chumar in 2014, Doklam in 2017. You saw it also in the Chinese approach to various other issues which bothered you, such as designating Masood Azhar. Most of all, you saw a huge increase in the Chinese commitment to Pakistan. In 1996, then President Jiang Zemin went and told the Pakistani Assembly, ‘You should do with India what we are doing, discuss your differences, your difficulties, but don’t let that stop you from developing a normal relationship, trading, traveling and so on.’ Of course, the Pakistanis didn’t want to hear that because for them everything should be, first settle Kashmir, otherwise nothing else, etc.

That was very different from Xi Jinping’s commitment to the China Pakistan Economic Corridor of $62 billion, and the kind of commitments they are making to Pakistan thereafter in the last decade or so. If you look at CPEC, it represents a Chinese stake in the continued Pakistani hold of Indian territory in Kashmir, because now they have assets there to protect. So there was a fundamental shift over time. I think some of us saw it as stress and said this modus vivendi is no longer good enough.

In 2020, of course, the Chinese tore up the modus vivendi because the basis on which it was done was to maintain the status quo and keep the peace. The border had stayed much the same until then, without fundamental changes. But in 2020, they tried to change the status quo across the line in the western sector. And clearly, that whole LAC [Line of Actual Control] is now live.

Podcast | We are still in crisis and need a full reset of India-China ties: former NSA Shivshankar Menon

The relationship needs a reset now. Whether it’s done consciously, or whether it just happens and evolves as a new normal, depends on both governments. They’re both saying different things. The Chinese seem to be saying, ‘Let’s just go back to the old days’. In other words, ‘We have done what we wanted to do, we have changed what we had to.’ And then they say, ‘Now let’s meet us halfway!’. That won’t work. We have been through this dance before, from 1959 onwards, 1959 to 1960. We actually went through very much similar kinds of arguments when China would say, ‘Okay, we have a LAC now, so let’s negotiate from here onwards.’

We are still in the middle of a negotiation of a crisis, because the crisis is nowhere near over until Depsang, Gogra [are resolved], there is a whole series of points. In any case, since the understanding has been torn up by Chinese behaviour, we have to actually see whether we can rebuild the relationship on a new basis or not. I’m not very optimistic, but I think the attempt has to be made. But as I said, it’s very hard in the middle of a crisis, while a negotiation is going on, to actually be either very optimistic or negative about this.

You talk about the role of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Depsang 2013 crisis, and this striking reference to the PLA essentially telling the Indian Army, why is India wasting all this time speaking to their diplomats in Beijing when the military could resolve it. Does the 2020 crisis and the PLA’s mobilisation along the LAC, even when China’s diplomats are saying something else, tells us that the PLA’s interests are now taking precedence over other areas of the relationship?

I think power in China has shifted in favour of the PLA some time ago and we are maybe one of the later ones to feel it. The Japanese, I think, felt it first when they had a deal basically on joint exploration in the East China Sea, and how to deal with the oil that was under the sea, which was basically torn up by the PLA which refused a deal which had been agreed to by the Special Envoy of China’s President and the Special Envoy of the Japanese Prime Minister.

You see this increasing role of the PLA across the board. In the South China Sea for instance, Xi Jinping as President promises no militarisation, but what do you see? You see continued militarisation in various deniable forms to begin with, Coast Guards used, what people call grey zone sort of warfare. You’ve seen a militarisation of Chinese policy everywhere. My fear is that if you have a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. I’ve seen this happening steadily with Chinese policy. The PLA has a much bigger say now in these matters and in how to deal with us, and certainly when it comes to the boundary, they count.

In your final chapter, on India’s destiny, you say we face two roads. One is a fear and polarisation, the other is one of self-confidence and ambition. Which way do you think we are heading at the moment?

It is very hard to say where we’re actually going. As somebody once said, pessimists are always right. But the optimists ultimately win. I’d like to be an optimist. But it’s very hard today to actually say which of these roads… It is clear from the book which road I think we should take, and what I think we should do in order to be true to ourselves and to our own people, and that is because that is our primary responsibility. I only hope the optimists win.

Source: Read Full Article