The difference between watching a movie on a laptop in your apartment and watching it on a big white screen is almost spiritual, notes Sreehari Nair.

Stepping out of my home for Seema Pahwa’s Ramprasad Ki Tehrvi, after almost a year of not stepping inside a movie theatre, I mumbled to myself, ‘A funeral comedy sounds just about right.’

A funeral comedy seemed perfect because of a general view I hold, that you don’t dispel feelings of gloom by aggressively shrugging them off, you do it through a process of assimilation, by dissecting the tiny components that make up gloom, by acknowledging their terror and sensuality.

(As a corollary of the above argument: ex-political prisoners will tell you that watching a straight rib-tickler, under a condition of house arrest, may not necessarily brighten your day, and more often than not, it can push you into a deeper funk).

Banking on my crazy theories and her acquired resilience, off we went, wife and I, to what we collectively saw as a married couple’s version of the matinee tryst.

Everybody loves Seema Pahwa.

Everybody wants to see her succeed, for she’s the luminous, off-centre presence that has made the ground firm for at least half a dozen small-town Bollywood tales of the last decade or so.

The tragedy of tragedies then that Pahwa’s directorial effort turned out to be a weak, if not a poorly done example of the genre we hoped would jolt us out of inertia.

For one, there’s a disturbing sensation that permeates the movie, a sensation that tells you that the director has her eyes set not on telling a story, but on ‘playing the director’.

The too-calculated long takes, the forcibly inserted slow-mos, scenes constantly breaking into piano-imbued melancholy (how I *hated* those piano interludes!) — the stresses in Ramprasad Ki Tehrvi are all wrong, and the movie is, for the most part, all heightened stresses.

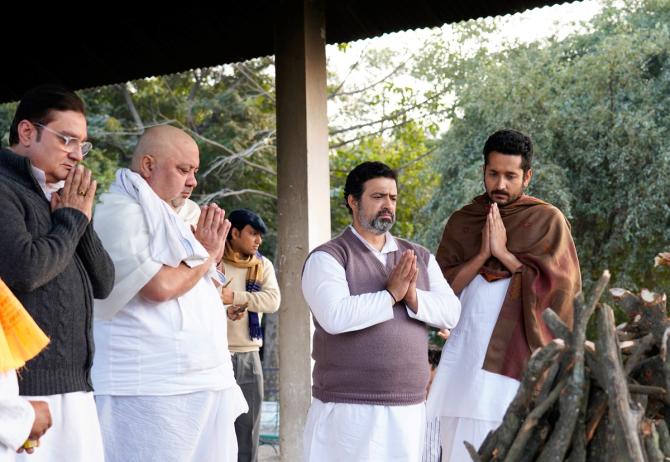

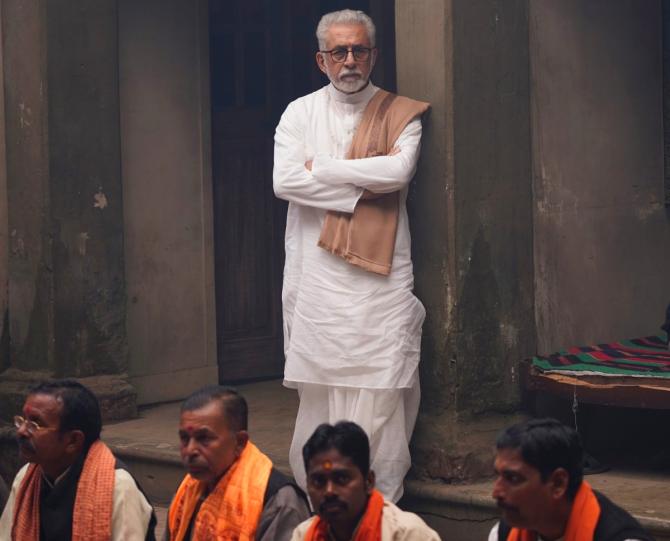

The title gives the basic plot away, but allow me to dress it up: In a lane-filled, smog-filled town of North India, a patriarch (Naseeruddin Shah) passes on, just as his wife (Supriya Pathak) yells irritations at him from the kitchen, and his children and grandchildren come together for the funeral and post-funeral proceedings wearing their two sweaters and their woollen caps knitted with pompons.

The reason for their coming together is grand but there are small things to be taken care of, and niggles to be smoothed.

Pahwa clearly intended this to be a behavioural comedy, a study in contrasts.

But Supriya Pathak’s somebody-please-acknowledge-the-widow face hangs over the narrative like a bad conscience, and the whole film is saturated with the sort of unfeeling that’s known to come about when an ironist tries for mysticism.

What one misses is the sheer wickedness of a film like Ee.Ma.Yau. — which had a similar setting, but also the good sense to interfuse death with comic details.

If there’s a consolation to be found, it’s in realising that Seema Pahwa’s debut film may have been conceived out of two noble objectives.

Number one: The core idea that she must have intuitively felt offered her a chance to dip into those lyric impressions of domesticity that she had been gathering all her life.

A funeral is essentially a get-together, any get-together is a cauldron of voices, bodies in movement, shifts of expression and egos, and if your desire is to be a poet of the every day, this cauldron can seem irresistible to you.

Not surprisingly perhaps, it’s to her bitchiest characters that Pahwa gives her most unalloyed impressions.

I loved the snide women in this movie, busy yet finding the time to be snide, women who taunt each other, gossip, fuss about, dig up old wounds, and expose the cracks in relationships even as they slice beans, or pass cups of tea around.

Pahwa’s second noble objective, one that bestows upon the venture a mission statement of sorts, is her wish to provide a slew of unsung names their due.

I happened to read a review which said that the movie doesn’t do justice to its celebrated cast.

And if you, too, end up feeling this way, it’s possible that you may have looked at the wrong actors for comfort.

Vineet Kumar (who appears in just two scenes but whose Mamaji knocks the wind out of the other characters), Yamini Das, Sadiya Siddiqui, Anubha Fatehpura, Ninad Kamat, the very fluid Divya Jagdale, Sarika Singh, and Alka Kaushal are actors who are *alive* in their roles.

Biggies like Brijendra Kala (who always needs reining in), Supriya Pathak, Parambrata Chattopadhyay, Manoj Pahwa, Vikrant Massey, Vinay Pathak, Konkona Sen Sharma (who reserves her worst performance yet for this movie), and Naseeruddin Shah (who, playing the dead, pleading-for-our-empathy patriarch, overacts through his silences) fill in as mere boilerplates.

Once the two sets of actors settle down, and Seema Pahwa’s over-elaborate style kicks in, the film seems to climax over and over again.

And after a while, the sadness experienced by Ramprasad’s widow may be experienced by the audience as pure sluggishness.

All this, by way of introduction.

What follows is the kernel of this piece.

Though Ramprasad Ki Tehrvi fails — and fails to a significant degree — consumed inside a dark movie theatre, the film hit me as a princely failure.

Why was this so?

The difference, I suppose, between watching a movie on a laptop in your apartment and watching it on a big white screen, which faces a great rear wall, is almost spiritual.

Now it’s a fallacy held and propagated by even intelligent film critics that in a post-COVID world, going to the movies should be set aside for spectacles, or for superstar vehicles that fill up movie houses.

I have always found arguments in favour of scale unimaginative, and the latest, deferred visit to our neighbourhood multiplex confirmed my belief.

Every movie experienced in a theatre, is, to a movie-crazed-goer, an Event; an Event where he, first and foremost, celebrates himself.

You are the star.

You dress up, try to look your best, and head off towards your designated theatre: that temple of shades, that pyramid secreted out of your unspoken dreams, where you see your self-projections being boldly played out.

Movie theatres are what make cinema, as Pauline Kael once described it, ‘the sullen art of displaced persons.’

And running through this celebration, like a current of irony, is the knowledge that what you are watching would not be played out for you more than once, that you cannot pause or rewind at will.

This knowledge forces you to concentrate better, which in turn lends an emotional centre to the whole enterprise.

There’s a sequence in Ramprasad Ki Tehrvi, of no real dramatic movement, but one that I don’t think I’ll ever forget.

It’s a sequence where Anubha Fatehpura (playing the elder daughter Rani) regurgitates her age-old discontents and uses that negative energy to make little bands out of a big ball of thread.

A simple passing moment, and yet, it took me back to an aunt or two, now long forgotten.

It’s not for nothing that you remember the mediocre movies you’ve watched in theatres more vividly than the good ones you’ve watched at home.

What direct-to-OTT releases cannot recreate is the Event-like texture of theatre-going.

Surrounded by familiar faces and gadgetry, too comfortable in the clutter that clings to our backs, and sprawled out in our T-shirts and three fourths, we may be inclined to treat movie-watching as an offhand informality, a chore among many others.

And without the speed, the immediacy, and the strict scheduling that invariably accompanies a theatre experience, if watching movies at home were to become the norm, then writing about movies has every chance of turning into an act of generic consumer-guiding as opposed to deeply-felt runways to the medium.

In such an environment of hard-boiled objectivity, how can a film critic discuss the links that films establish with our private thoughts?

When ‘should I watch this film or not?’ becomes the overriding question, how can one talk about aspects such as strangeness and transcendence, or talk about the many kinds of innocence to be lost at the movies, without coming off as a deranged poet?

Isn’t it an unremarked feature of cinema magic that watching a movie in an intimate corner of our bedrooms we turn into prim public individuals, and among a set of strangers in a movie theatre we are put in touch with our most intimate side?

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article